Features

Features

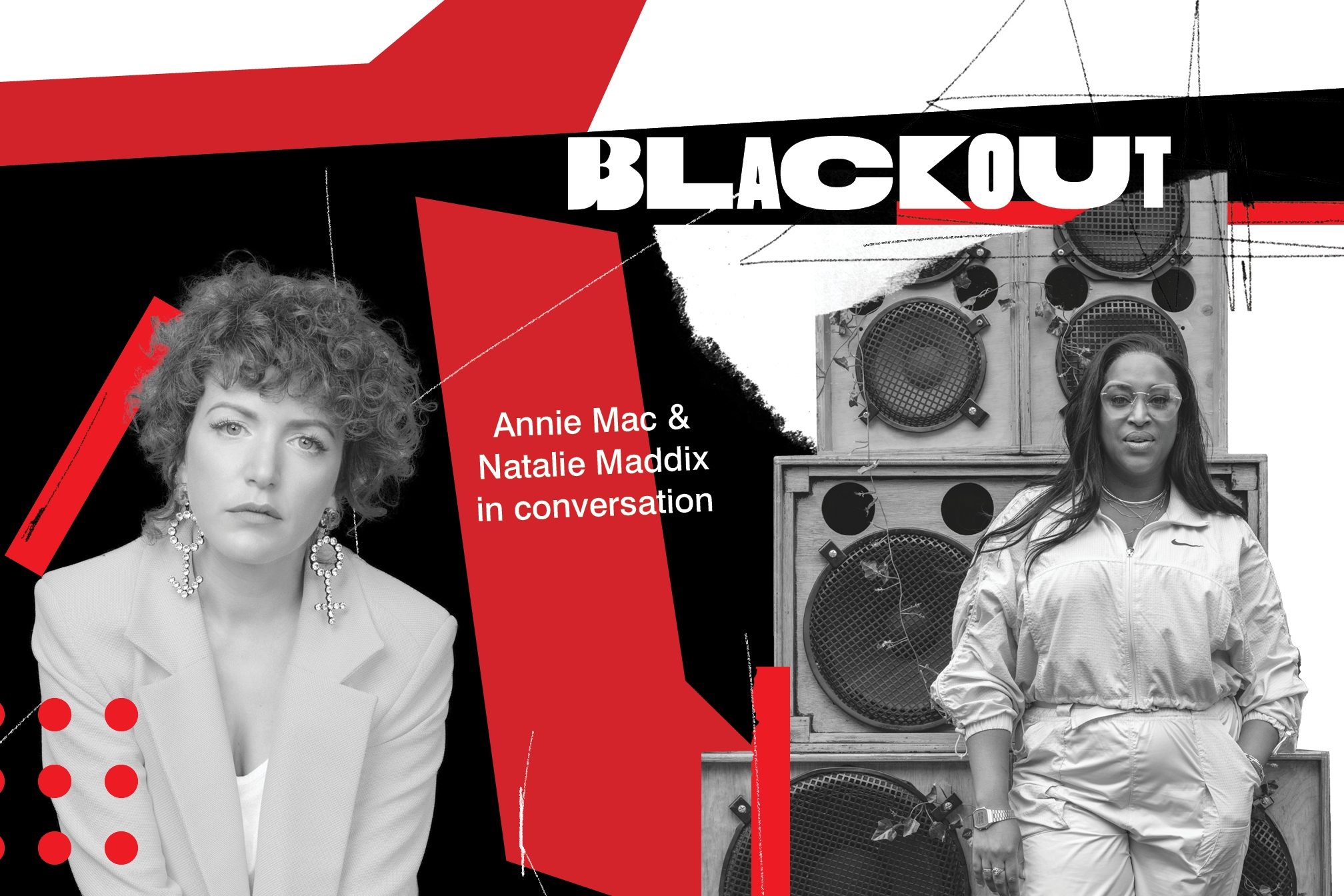

Annie Mac: "There's not enough Black people in every level of the music industry"

Annie Mac and Natalie Maddix of House Gospel Choir talk race, power and business in the music industry with Jasmine Kent-Smith

On June 2, Funk Butcher picked up his phone and offered the Twittersphere this question:

“Shall we talk about Black female vocalists on house music tracks used for authenticity but never making the visuals for the marketed video or worse yet credited as the featuring act?!”

The tweet sparked a brief but conducive chain reaction that lead us all right here to this article. His words resonated: as both the founder and creative director of House Gospel Choir and as a Black woman who has worked in various areas of the music industry for some time, I have had a front row seat to the very real issue that Funk highlighted. Meanwhile, somewhere on the other side of the internet, Annie Mac had also hit that like button to Funk’s tweet. In turn, Funk reached out to us both to propose the idea of a conversation between Annie and I; Annie as a bad gyal dance DJ and myself as a house music artist. So we both got to thinking and came to a Zoom call armed with some questions.

This conversation between myself and Annie Mac is a reflection of our own personal experiences, our understanding of how things work (or don’t work) for Black people and specifically Black women. I am proud of the fact that one of our country’s most prominent radio DJs has such a deep understanding of the problems that we face in this genre of music. Annie was willing to share what she knew and listen to me on the areas that have not played out in front of her.

What follows is an excerpt of that conversation that I am eager to share in the hope that it will provoke further conversation on a subject that stays close to my heart.

The conversation was moderated and transcribed by Jasmine Kent-Smith.

How do you know each other and how did you start working together?

Natalie Maddix: I know Annie Mac from the radio! [laughs] And Lovebox [2015] and she did a set and it was just fire. I was like, 'Who is this woman!?' Her selection is crazy and any party she's in control of is just sick. Then we got to work together. I sent an email to [Annie’s representative] Lucy, but I think at the same time someone had already shown her a video of us performing somewhere. So, it just kind of happened that way and then we got to perform with you at Annie Mac Presents (AMP).

Annie Mac: I remember my friend Sarah Carley, who’s part of my management team, sent me a video because I was saying I really wanted to work with a gospel choir. We wanted to try and do something different. I was pregnant with my second kid and I was looking for new ways to challenge myself and push myself forward in terms of the DJ sets. The reason why I love dance music in the first place is because of gospel and soul and the very origins, the Black origins, of dance music. I've basically always wanted to be in a gospel choir.

N: Now you are, you are an honorary member of the House Gospel Choir to be fair!

A: So, we reached out and you and Shez [ShezAr, HGCs’ choir director 2014-2017] came to my house. We met up and ended up working together and had such a lovely experience, in my perspective anyway. I'll really treasure it.

N: Mine too. Especially some of the stages we got to perform on. We wouldn't have been there at that point in our career if it hadn't been for you. Doing the John Peel stage at Glastonbury that night was just like, 'What?!'.

A: Remember when we did that massive one...

N: We did V, we did V as well.

A: V. Yeah!

N: That was a big night, that was massive. I forgot about that! We've done some brilliant things. And also, the songs that you gave us to put into our set kind of changed the sound of the choir. It helped us move forward because we do a lot of classics but then Annie was like, 'Have you heard

Floorplan 'Magnify' and the Gotsome edit of Kanye's 'Fade'. Here were all these songs that Annie just showed us and shared with us. As a selector, and a tastemaker, Annie knows tunes.

A: Also, DJing is a very solitary experience. I've always been jealous of the people who've DJ’d in twos because I've always thought it's so nice to share the fuck-ups and the good parts with someone else. I've always found that being on my own, the whole performative side of it I've always struggled with. So, being able to share the stage with this huge, vibrant amazing group of people was just such an epiphany. It was like, ‘Oh my god, it feels amazing to just bounce off you guys and share your energy.’ I loved it.

The whole springboard of this issue is the first thread that Funk Butcher put out discussing the omission of Black female vocalists, music makers and behind-the-scenes figures who weren't included in marketing visuals, weren't included in videos and weren't included in credits either. How did it make you both feel to read that in the first place?

A: When I saw it, it was very real and very raw. When you see it, all spelled out like that – you're really seeing it for what it is. I found it to ring really true in terms of what I've seen in house music and the industry and how it works and what I've learned about how it works. When you read that, and then you look back at all of your favourite dance tunes and you try and remember the videos or you try and remember when you've seen the voice or even heard the name of the person who's singing, and you realise it's so rare when those people are pushed to the forefront of the campaign of the record. So yeah, I think it rang really true for me.

N: It definitely rang true. The one thing Black Lives Matter, the whole movement, has really highlighted for me is how much we didn't say, or how much we wouldn't have a conversation about things in public. Because this is something that I've been aware of and, in an honest moment, it's a big reason why House Gospel Choir even exists. I'd be raving to a tune for years and then one day it's like, ‘Who sings this?'’ ‘Who's voice is this that I'm just absolutely in love with… I just know the producer's name’. I want to know who Kelli Leigh is, I want to know who Barbara Tucker is. It was really hard to find background on essentially my favourite artists. I think I was just shocked that someone was being so open about it because we're really polite about the things that we know aren't quite right.

A: Because it's systemic and it's always been this way, from the other side, the industry side, the side with power, they are like, 'It's just how it is, it's how it's always been done!'

N: And if you ask someone why it's like that there's not really a good explanation.

N: Being told somebody isn't marketable because they're Black is a bit… Their voice has moved you sufficiently to record them and put this record out. They have so much value and worth, why can't you see their faces?

A: I've always been quite ignorant to how the technical side of ownership of songs works behind the scenes. We did our AMP conference last year and I interviewed Raye and Mahalia about what it's like to be a female pop star in the world today. Both of those are songwriters and both of those have written songs for other people, but they are in a position now where they will have their name on a song, and they will want to be put in a video because they have pop star profiles. I found it really interesting how they said the hierarchy of power works within a song. The songwriter is at the bottom of the pile when it comes to ownership of a song. The producer is top, and then what happens is the songwriter will come in, do a session, write their song and then, if on the small chance it gets chosen, 99.9 per cent of the time it won't – so you are always earning on a basis of risk – if it does get chosen, a lot of the time they'll pull in a big name to come and sing it. The songwriter doesn't get any of the money or the profile from the performative side of things. They get a small percentage of the publishing when everyone else gets [paid properly]. When they broke it down it was quite shocking.

Then there’s a whole element of never knowing when your song is going to get chosen, so your whole life is based on the choices of other people. You never have ownership of your own work. Then there's the weird politics of the studio that are really non-regimented in a negative way for [songwriters]. It's always based on someone's word. Like, 'Oh, they were there, and they wrote that song, but then they wrote that, then he was there so I think he played keys there and he did that'. At the end of the day, you have to be the strongest personality in the room to go, 'Actually, no. I wrote that entire thing'. And it's always one person’s word against another. So, if you're a lone Black woman and you're surrounded by people who are white and mostly men who are behind the scenes owning the rights and the publishing and all that…

It's so intimidating to have to fight your corner. They were saying there is so much of it that's just based on power and again, that system of someone being in charge of something that you're not. What Raye was saying, a lot of the time if the producer is a big producer you're just like, 'Yeah, you can have thirty percent and I'll take the five' because you don't want to piss them off and you want to work with them again.

There's an internalised sense of, 'You should just be grateful for what you're being given' which is completely incorrect but it's so ingrained that, 'I should be thankful that they are working with me and I should just be quiet and take it' which isn't right.

N: I had a situation last week, a producer said: 'The amount we wanted to charge for this session, for him to record five [of our HGC] vocalists, would be okay if we were doing a million streams a month'. I was like, 'What do you mean?' It's like, 'Well, that's how I'm going to judge how much you're worth'. That's never been a metric, dude. If you don't have the budget, you don't have the budget, that's a different thing, but the disrespect when someone says to you, 'You don't have enough streams to warrant...'

The rules just keep changing. And actually, if you needed a vocalist and if you needed a gospel choir which, let's be honest, that's a particular sound you're looking for on your record, then you have to come at it with some parity and some respect in the conversation. That’s still not happening. That was literally last week. I saw the email and I was like, 'Oh, okay, well, great not to work with you' because we're not doing it anymore… How do you justify sending five people somewhere for an amount of money that doesn't cover them for the day?

A: The bit I find really interesting is who is the God here? Who is the person deciding? At the end of the day, someone is drawing those lines, and someone is putting value on them. Maybe there should be some sort of regularity to it where everyone agrees on a base system of how much or a percentage that songwriter should get no matter who they are or what happens. What do you think about that sort of regular system?

N: If the producer is your friend and you want to go and do a session you should. I'm not saying everything needs to be paid for. There is magic in the creativity and the creation of the music. But, if someone is putting together a commercial product, and they want to make money from it, then they have to have that in mind. We started a vocal agency called REP (Record Everything Properly) to balance some of this stuff out. I just saw time and time again some of the vocalists cc-ing me in on emails when it came to negotiating their rate or their buyout fee or how they handle their publishing. I know all that through trial and error or working in the industry, but they don't have that information. There does have to be some regulation and I do think vocalists and songwriters need to come together. Obviously, we have songwriters’ spaces like PRS that offer advice and information. But for vocalists, it's a bit like the wild, wild west out here.

A: When you as a gospel choir were signed to a major label and found that you were creating music from scratch, how did you find that aspect of ownership and payment?

N: I think first and foremost, I'm managing a business, you know, I think [that’s the] part of the work that so many people get wrong. There's the music business, the business of making the music. Then there's the music industry, which is about exploiting that product. So many people, especially singers and songwriters, enjoy the process of the music business, making the music and being in the studio, but haven't got the information about how to exploit your product in the music industry. We have conversations with producers before we do the session. It's like 'We're coming in, we'll split it however many ways [between the people] in the room'.

A: Raye in that talk said that now, that's what she does. Before she goes [to the studio] she says, 'I'm going to need this percentage before I work with you'. Which feels like a sensible thing to do. But the fact that it's only taken her until now for that to be a thing, and to have that position of power where she can do that with those big-name producers...

N: Growing up I just thought producers were boys. I didn't have any reference for girls as producers, or engineers. Especially studio engineers – that's a ‘boy’s job’. The girls sing or they write, they might play some instruments, but those [producing or engineering] are the boy’s jobs. Getting a laptop, learning how to use GarageBand and Logic, and looking over engineers shoulders actually showed me I could do that… But we're just educated to the idea that these things are, and that's what the boys do, and the girls come in [to sing]. So that's already handing over your bit into their machine and you walk away and hope for the best. Hope that they're going to honour some agreement that you haven't made yet.

A: There's a lack of control there from the outset isn't there.

N: Yeah. I started going to studios when I was 13 or 14, so you grow up into that system. The other thing as well about those spaces is whether or not they feel safe for women. I've had some really great experiences [and] I've had some really not so great experiences in studios, because some people aren't always there to just make music, you know. And I like writing songs at 11 o'clock at night. Because I'm a girl, I shouldn't go to the studio at 11 o'clock at night. So, I think there's a real thing about creating spaces where we can make stuff ourselves.

Is that something you've seen more of in recent years?

N: Yes.

A: It involves having loads of money as well. It involves having a lot of money to rent somewhere that isn't your house as well as your house or your flat. So, you have to have an element of success to do it. None of those people starting up and going through those ranks are going to be able to do that.

N: I think singers often think of their voice as their instrument and it's all just their body. But actually, you need these recording techniques, you need this space, you need the equipment that's all another part of [making music] and singers sometimes have this real disconnection between…what we do with our bodies and how we make the product.

A: How have you been Nat and how has the mood been in the choir since the Black Lives Matter movement has happened this year in 2020?

N: Interesting. Obviously, we're coming from a place of Black music but as all good music is for everybody, there's no barrier to who can sing it or who can be in the choir. It's a really mixed group of people, really diverse. And I was like, ‘We know this’. Everyone knows that Black Lives Matter. It was a few months ago, before it all kicked off, I decided just to send them a message like:

‘Guys, we need to talk about this. We are proof that everybody can work together to make something great. We are absolute proof of that with the things we've achieved with what we do for a living and the people we've reached.' We actually have to take the responsibility of showing people, 'Look, we are supposed to work together.' We can call it Black music and still work together. No one's excluded. It's not a bad thing to say gospel comes from Black expression, that house music comes from Black and gay people and how it is presented is the problem, but we have an opportunity to talk about it differently.’

I was really overwhelmed with the response, especially from our white members of the choir who just started sharing resources straight away. They were doing the work already. That was what was really interesting as well. For some people it definitely was a catalyst for them. And that was really heartening because I had a really scary moment where I was like, 'What if no one knows Black Lives Matter?' Like in this choir, like how important it is.

A: 'Can I just check that you all know that Black Lives Matter'

N: [Laughs] 'You sure you know, right?'. There were a few [members] that definitely weren't aware of the situation. That's to be expected, because you don’t necessarily experience it every day… How have you found it Annie?

A: Really, really a sobering and really eye opening. I mean, I've always been interested in the history of it anyway. As an Irish person who's very aware of imperialism and colonialism at its heart and have learned that in history, I've always been aware of some elements of the history of slavery and read books on it and all that. But what I find interesting this time I guess was the Britishness of it all. Like, looking at what happened in America and then having it shine a mirror on everything that's happening here. And hearing stories about police brutality in this country and remembering the daily shit that you have to go through as a Black person, from people getting pulled over in their cars to micro-aggressions to all of that. Then just looking at the people around me, as everyone should have done, as most people did, looking at your own situation and thinking, 'Am I doing right by my Black friends? Am I doing enough? Do I have enough people around me working in my team that are diverse?' All of that. Looking, you know, at the shop floor on Radio One, the staff there, everything, and just seeing how predominantly white everything is and how I'm sat in a position of real power surrounded by a team of mostly white people. I'm most definitely part of a systemic problem in this country, in the music industry, where I have spent decades now doing really well in music, because of my deep and enduring love for Black music. And I have profited from that. It was a very raw wakeup call because I've always known and been very public about how much I love Black music, but when you think about it in the context of Black Lives Matter and the kind of systemic situation where you’re thinking, 'Should someone else be in my place? Do I deserve to be in this place? Do I deserve to be doing what I'm doing? Am I uplifting people enough? Am I supporting people enough?' All of those thoughts went through my head obviously and I'm still thinking about it. I'm still trying to figure out what I can do with this small power I have in music to change things. And we've had the conversations and we've always been very aware of gender stuff in terms of what I play and the people that I book. We have been very aware in recent years, you know, not enough from the start but definitely in recent years of making sure that we have a really diverse line-up in our festivals in Malta, making sure we have enough diversity in the radio shows I do. Finding the Friday one is really hard, because there's not, there's just not a lot. Of course there is dance music made, great, amazing dance music made by Black people. But it's just constantly trying to find it and push it forward to make sure that we're supporting it enough.

N: Many Black artists don't know that you need PR or need a plugger. They're just making great music that isn't always getting to where it needs to get to because of that barrier. Is there something we can do to demystify that?

A: It's so interesting, the industry and how it works. It's exactly the same as what we were talking about with studios and songwriting systems. There are systems in play. And if you feel outside of that system then it feels hard to penetrate, because mostly the system is about knowing the right people to get into an institution or platform or wherever in the first place. Then once you're in, it's having the confidence to push yourself forwards. It's also having the money and the headspace and the time to be able to push yourself through. Plugging is a really good example. It's this line that's been drawn between the music makers and the output, the radio outputs. And the reason why pluggers exist is because mainstream radio...I mean we, on our shows, the remit is literally contemporary music. It's so vast that it's kind of overwhelming. There has to be some sort of a filter system. So, your producer and your assistant producer will work kind of filtering the music that's coming through. Anyone can sit down with a Radio One, anyone should be allowed to do that, it doesn't have to be a plugger it could be anyone. You can make appointments with them. I don't think a lot of people know that.

N: I didn't know that.

A: The pluggers are paid to put the music in front of me or in front of my producer and sell it. And that's another thing that I've been really conscious of in the last few months. You can really see the system working around you. When I say you, I mean, me, I can see it working around me. There's a kind of expectation and a sense of entitlement nearly at the idea of you launching this record. It's like: 'Well, we want you to launch it'. There's an assumption based on the ‘right names’ and the ‘right support systems’ being around an artist that it's going to be played in the right way by the right DJ on the right station. I'm very conscious of that, and I'm very conscious of making sure that we don't slip into the net of always just saying yes to those people. It's really important to be seeking out those records that move you. The records that you are emotionally moved by and passionate about. And if they don't have a big marketing budget behind them, or they don't have a major label release and it might be that not much happens with that record.

That's a fight to fight because, again, it's systemic. Everyone feeds you things and it's been happening for so many years that they don't understand why you're not saying yes to that record when that artist is huge. They've got all these subscribers and followers and YouTube views and, 'Why would you not play them; you have a duty to your audience to play them'. The problem is, my audience has only ever heard them. So, you have to find ways for them to hear new people and new sounds.

N: That point you made about that filter between the music makers and DJs playing records. Do you think that filter is broken?

A: The problem is Nat, the filter in my case is two white people. And most of the pluggers are white people, the majority of them. So, it's always through the prism of a white person's experiences.

N: It’s not fit for purpose in the sense of there's this vast sea of great music available, but it's coming up through this filter that isn't fit for purpose. [T]here is nothing to stop them having Black pluggers in their team.

A: The biggest problem that I can see is that, as you said, there's just not enough Black people in every level of the industry. And we need the very core of the industry, those very tip top jobs, the MDs and the heads of A&R and all of these, we need Black people in there. It's essential. Because until there is there won't be an honest representation of the culture and how we can all work together. I think it's important that you have white people who are also looking out for Black music. It shouldn't be all on the Black people to do that. That's another thing that's come out of the Black Lives Matter movement that I've been really conscious of and that I'd never thought enough about before. The idea of putting everything on Black people. Asking them: ‘What's your history? What should we be doing? Am I doing this right?' You have to learn how to figure out a world of diversity yourself and feel it out and take the time to educate yourself.

N: This is something we definitely experience, trying to explain what House Gospel Choir is as a product and a project. It's a soundsystem, more than anything else, and if you don't understand soundsystem culture and how important that is to British music history period, not just black British music history… There's this real sense that people don't know the history of the movements, which is politics because those sounds came out of struggle. I think dance music especially is marketed in this way. That's just about good vibes, high vibrations, euphoria, getting off your tits. All of that is great. It's all part of it. It offers escapism from reality, which is good too, like, your music should do that. But what are we trying to escape from? When are we going to look at the reason we need to escape?

A: Yeah, the whole political thing is really interesting to me. Because talking about those people who are working at major labels and don't understand the cultural significance of soundsystems or whatever, it's like all the best kinds of genres of music started out of frustration. As you said, dance music started from people who were extremely marginalised from society, extremely othered. It started as a solace and as a form of escape and kind of solidarity for them. And when you see what it's turned into it can be quite depressing, I think.

N: That messes with people's escapism, right?

A: All the joy and all the pain. It's like what Clara [Amfo] said on Radio One, 'You can't have the rhythm without the blues'. You have to understand the pain and the politics that come from the style of the genres. In the industry, I think there [seems to be] a kind of blinkered situation. It's all down to cold, hard cash. And culture really gets bypassed a lot, I think.

A: What do you think Nat, you can't obviously know the answer to everything but like, what do you think some pragmatic ways of helping the industry move forwards in dance music for the better?

N: Employ more black people. That's a starting point. Not as tokens, because there are excellent Black people. [The industry’s] developed a language that separates what is needed from the ability to do a job. But the value in that person, the knowledge, the experience, the love, the passion for music is there. There's bound to be some amazing people that are going to be right for those jobs. And they need to be on these teams. They need to build plugging teams; they need to be in the label, and they need to be in the marketing departments. We'll talk about that another day.

A: I think ownership is so important. When you look at a lot of platforms out there, media platforms that are predominantly white, but might think that they represent the culture well, or that they speak for the culture, but still within that the core of the companies are predominantly white.

N: If I get deep for a sec, I think there is this real sense that what Black people do well, we do easily. Like, 'Oh, you can sing. Oh, you write songs. Oh, you produce. That's innate isn't it, because you're Black'. What's innate about setting up a radio station, what's innate about [training] yourself to become a good songwriter, or the amount of time it takes to learn Logic well, to produce a beat? That person might have a good rhythm, but they have to be good… But the minute we try to put a value on what our art is worth, there's this push back. And like I said I had this last week and people decide what you're worth.

A: Equally from the other perspective, white people need to understand the value of the skills and talents of Black people and understand it's just about parity, isn't it? And looking at how you're treating someone and looking at how your thought process has worked. How have you come to the conclusion that you've come to about this person? And why have you? Really try and think. There's deep rooted shit that people don't even know, it's unconscious. You have to take the time to really, like explore your thought processes.

N: And it's tiring, I get it. People are exhausted right now. Forget the reading. the external stuff, like understanding your own thought process and why you're going there. But you just gotta keep doing it. Like, we're tired, very tired of having to play this game. And I'm really grateful that this conversation can even happen and we're talking so openly. I couldn't imagine this a year ago Annie.

A: That's the other thing that I feel ashamed about, that I haven't gone to the people that I've worked with that are Black in the past, pre-BLM, and said, 'Are you alright?' Like one of my oldest best friends Reju, she's fucking grown up around racism all her life, but I've never once sat down and be like, 'Tell me about what you've been through'. You know what I mean? I feel ashamed for that. And it's good this [movement] because it's making people really think about how they treat Black and brown people around them. It's just making people pull themselves up and check themselves. That can only be a good thing.

Annie Mac is a journalist, broadcaster and DJ. Follow her on Twitter here

Natalie Maddix is the founder and Creative Director of House Gospel Choir. Follow her on Twitter here

Jasmine Kent-Smith is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow her here

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs