Features

Features

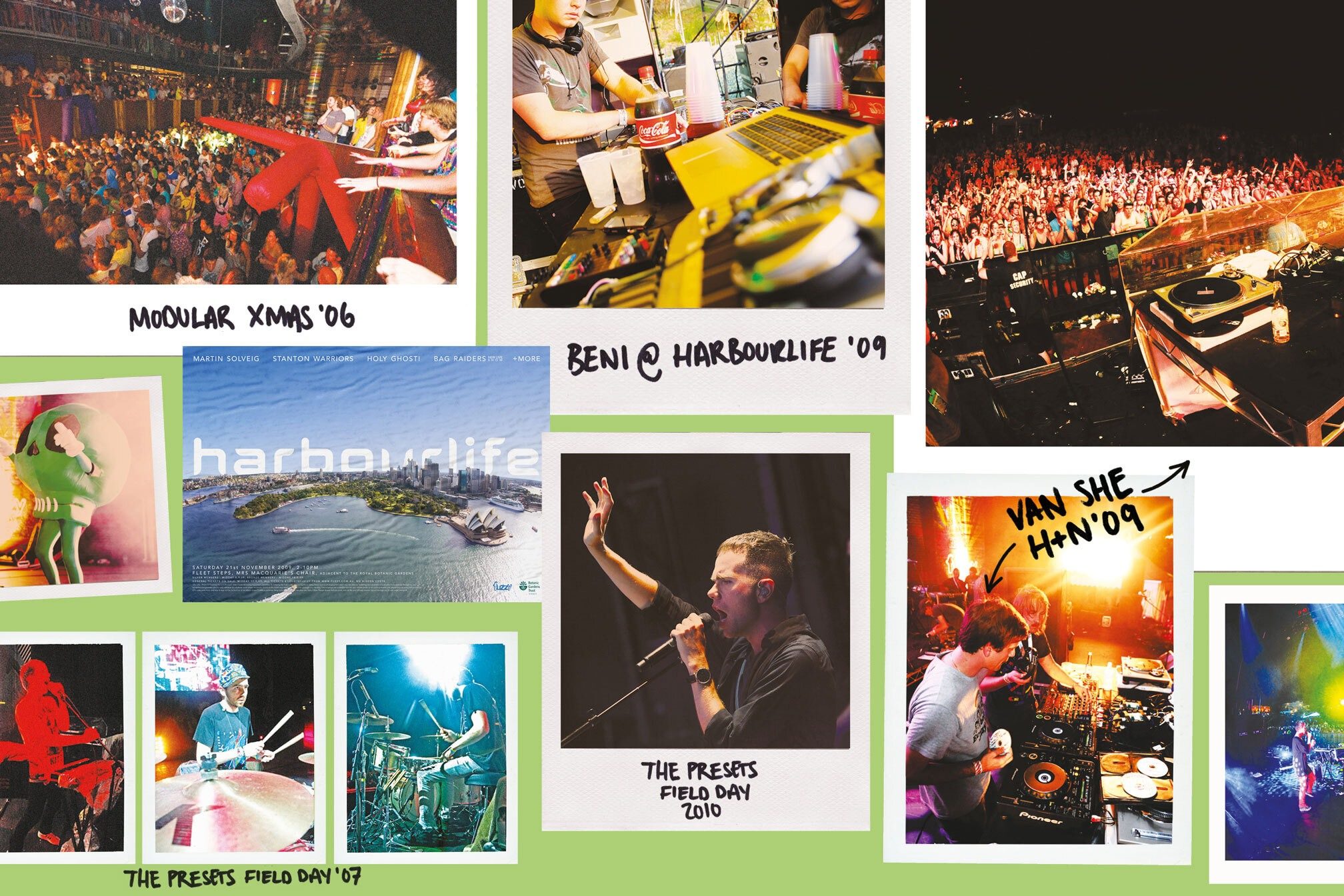

"Everything just collapsed into everything": Australia's golden age of electronic music

A look back at a time when Australian dance music was finding its own identity and "there weren’t any barriers anymore"

The Presets’ Kim Moyes remembers struggling to stay on his seat behind the drums as a churning tidal wave of energy from 50,000 Sydney fans – hearing the opening tracks of their monster ‘Apocalypso’ album live for the first time – crashed into him with the force of a comet.

It was December 22, 2007 – and The Presets were the support for Daft Punk’s ‘final’ live show as they wrapped up their tour in Australia at Modular’s Nevereverland at Sydney Showgrounds Arena. The festival was organised by Australia’s Modular label, described that year by Mixmag as “having the world where rock-meets-rave by the short and curlies”. That grip wouldn’t abate for another two years, as Australia’s golden age of band-driven electronic music peaked with chart-topping releases from The Presets and Cut Copy and began 2008 with albums from Pnau, Van She and Midnight Juggernauts to strengthen the scene’s vital power.

“‘My People’ had come out on the radio maybe a week before we did the Daft Punk show and we came out with really no expectations,” says Moyes. “We were sort of in a bit of a bubble just trying to get our music finished, and we had this big gig to go and support Daft Punk. We were massive fans, so it was a really big deal, and we knew it was a big deal, but when we got up on stage and played ‘My People’ and ‘Kicking And Screaming’ amongst our older material, and we actually saw it set the crowd on fire... We were like, ‘Holy shit!’ It was huge, and that kind of feeling really kept going right through till the beginning of 2009. For a good year and a half or two years, every show we did kept getting bigger and the energy kept getting bigger, it was wild.”

A year later, The Presets were Nevereverland's headliners, having stormed through the year scooping up awards and elevating Australian electronic music to levels of success never seen before – joined in this by Cut Copy, who also brought a frenzy to wherever they went.

Read this next: Is Australia's festival scene the best it's ever been?

Cut Copy’s Dan Whitford recalls the shock and disbelief of ‘In Ghost Colours’ debuting as number one album on the ARIA Chart (Australia’s overall album chart) at the start of that year, breaking new ground for a local electronic band before The Presets did the same a few weeks later.

‘Apocalypso’ went to another level of ubiquity, hype and recognition in the bands’ home country, while ‘In Ghost Colours’ launched Cut Copy overseas, especially in the United States where they were possibly even bigger than in Australia. The vibe around Modular, which put out both albums, and at parties, gigs and festivals, such as Fuzzy’s Parklife, was surging and fresh.

“We were just doing our own thing but somehow that connected with the mainstream, and all of our bands had a really fruitful period at that stage,” Whitford says. “It was definitely a heady time.”

Key players point to The Avalanches’ ground-breaking 2000 album ‘Since I Left You’, one of Modular’s first releases, as a turning point, the first motion of what would become a movement at the start of the new millennium. This was what Australian electronic music could be: interesting and internationally acclaimed. This momentum later came into its own as the Melbourne and Sydney scenes found themselves connected between 2003-06, defining a decade of Australian music that was fading out by the time it clicked over into 2010.

Label founder Stephen Pavlovic started Modular in the years after getting his first demo from The Avalanches, releasing the Melbourne collective’s ‘El Producto’ EP in 1997 on an earlier imprint, and Moyes and Whitford cite the album as a big influence on their formative periods. Whitford then signed to Modular as a solo bedroom artist, releasing Cut Copy’s first EP ‘I Thought Of Numbers’ in 2001 – which also helped inspire The Presets – before bandmates joined for 2004’s ‘Bright Like Neon Love’.

There was no live electronic scene to speak of in Melbourne, so Cut Copy cut their teeth playing on bills with punk and rock bands, something Whitford says they were probably grateful for in the long run: “in a funny way” it probably honed their energetic live shows – they had to be compelling as stylistic fish out of water. The local landscape, meanwhile, was made up of genre-specific nights.

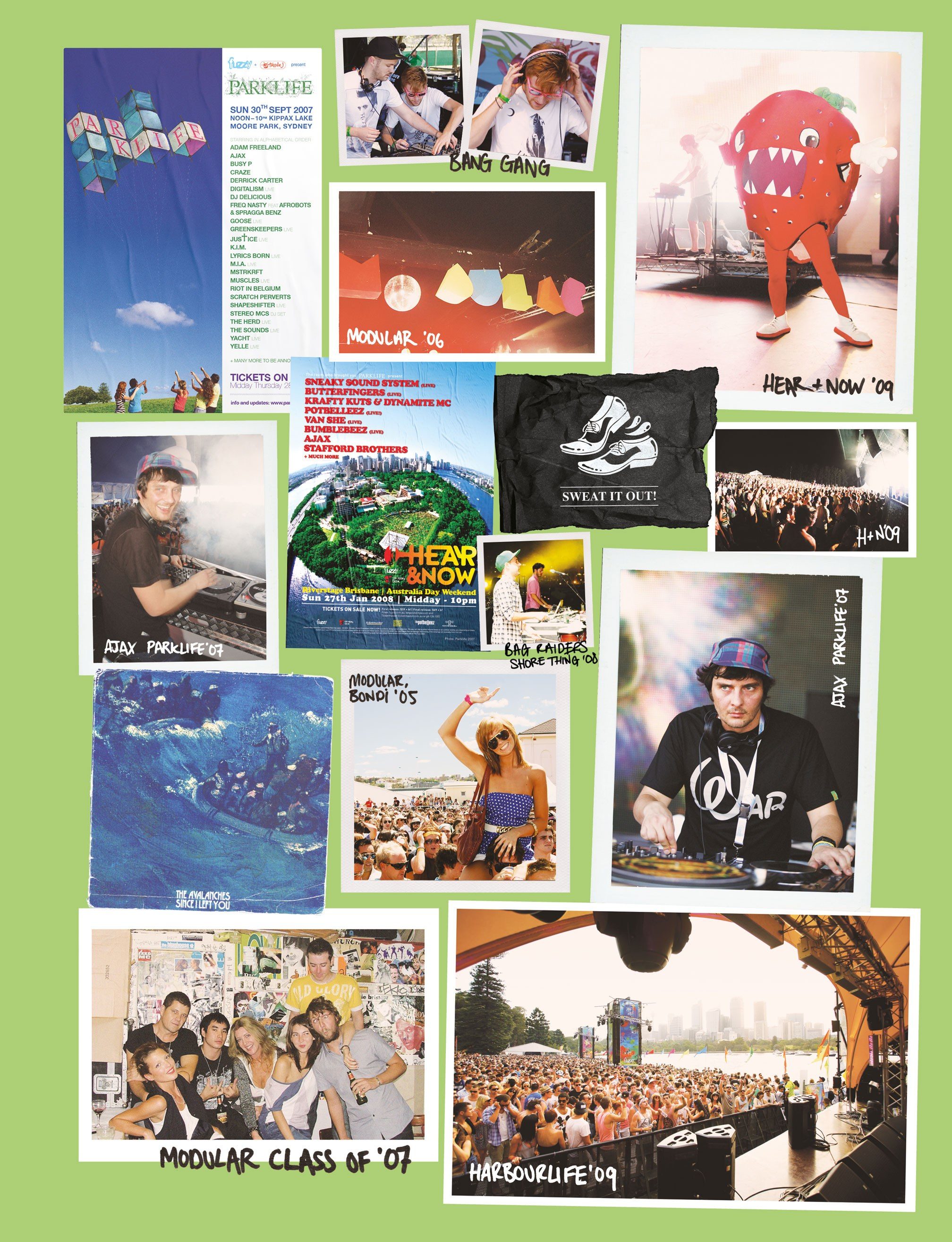

In Sydney, it was a similar story, but the pioneering Bang Gang Deejays, centred around radio DJ Ajax, aka Adrian Thomas, who sadly died in 2013, changed all of that. Sweat It Out director Jamie Raeburn, who founded the label in 2008 with Ajax and Matt Handley (of Yolanda Be Cool), says of the collective’s parties at the 50-capacity, “tiny little sweatbox” Club 77, near pre-lockouts clubbing hotspot Kings Cross: “It was different because it wasn’t house music, it was just everything… anything and everything gets thrown into the mix... he (Ajax) was dropping hardcore at one point, it was just nuts, but it all worked.”

“It felt Australian,” Raeburn, originally from the UK, says of the burgeoning scene, different from anything he’d experienced. Australian dance was finding its own identity, raw and free from ego – and all the Sydney names were there, inspired and connected.

Moyes also recalls that influence. There were hedonistic, “well established” and “quite educated” parties “steeped in rave culture” already, but Bang Gang and Ajax combined it all, redefining night outs: “There was the techno party, there was the jazz party, there was the indie night and whatever, but around sort of 2002-2003 it all felt like everything just kind of collapsed into each other and there weren’t any kinds of barriers anymore.”

Read this next: Strawberry Fields is at the forefront of Australia's thriving 'bush doof' scene

He and Hamilton went to music school together, both studying classical, and blew off steam going to clubs and listening to electronic music, which they always connected with. They were “bumming around as session musicians”, got to know established producers like Paul Mac and Pnau’s Nick Littlemore (Pnau’s immaculate but legally troubled masterpiece ‘Sambanova’ was released in 1999), learned about that side of music, and were in a band called Prop with other members, which The Presets was born out of after rehearsals one day. Moyes remembers a turning point for the Sydney scene in a disaster that changed the world.

“The atmosphere of Sydney around 2000-2001 was really changing and I can kind of look back to it now almost like there was a real definitive point after 9/11. I know we were sort of on the other side of the world but I remember the week that 9/11 happened, it was such a massive shift for everyone… Everyone was in shock for a few days, and then after a couple of days everyone went out again and the atmosphere when we were out after that point just really seemed to change. I really felt like everyone wanted to take advantage of being out, of having a good time, of being amongst their friends, of living as fully as they could, and from that moment on I just felt like it was really quite a watershed moment in my life, and I think everybody else’s. Everything we’d been doing up until that point kind of didn’t seem to make sense anymore, and it really felt like there was this new energy injected into where we would go out, or what people were playing, or what we wanted to experience. It just kind of fed into what we wanted to do creatively and where we wanted to be as people.”

Indie dance/electro was also bubbling in other cities such as Paris and New York, via respective labels Ed Banger and DFA, but “the Australian thing was definitely its own thing”.

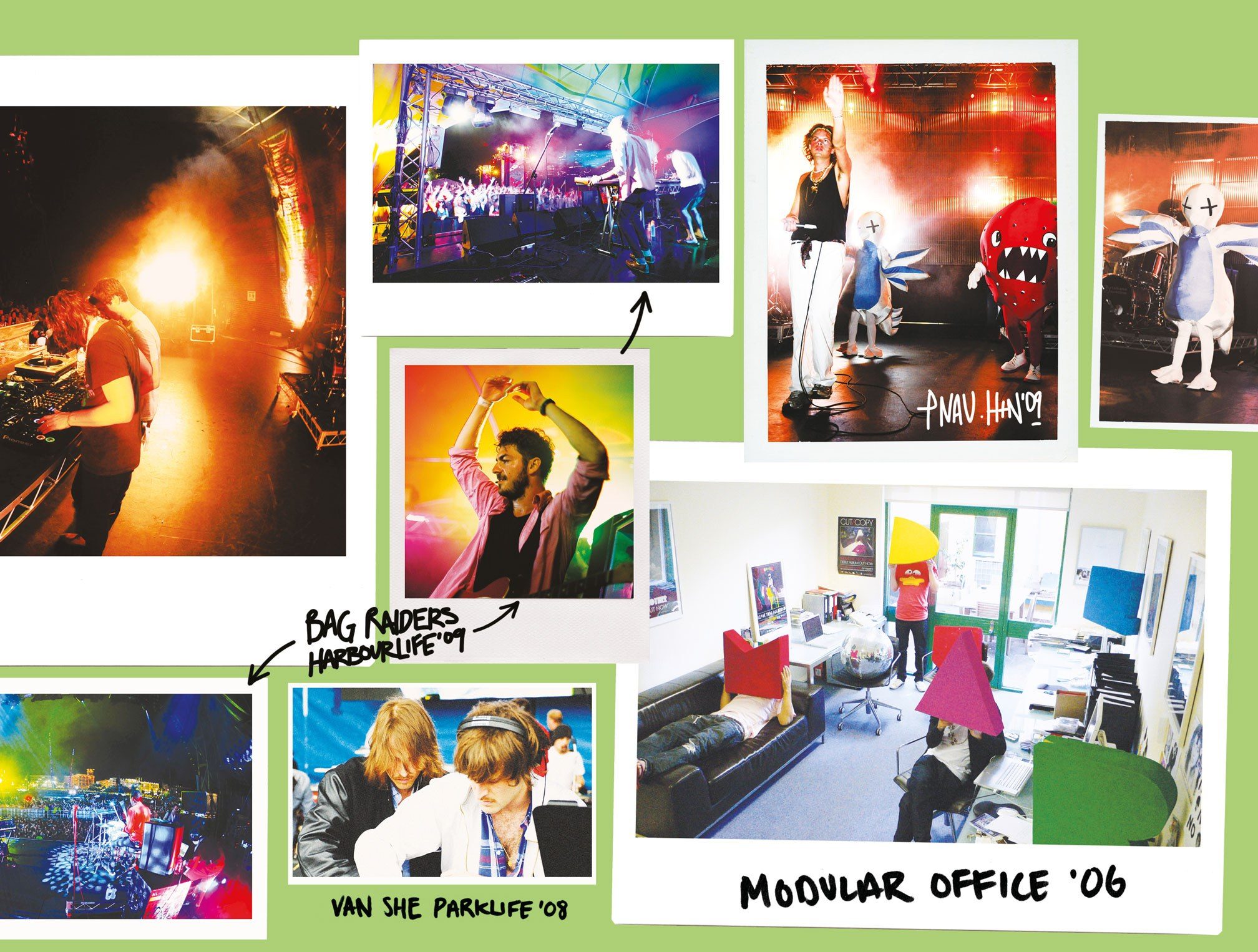

As Modular became the central label to that Australian sound, a supportive community of kindred spirits and like-minded people fostered from Melbourne to Sydney. Melbourne artists Cut Copy and Midnight Juggernauts became friends, with Honkytonks (which later became 3rd Class), the central club in their city, “kind of like our Haçienda”, Whitford says. The artists were bouncing off each other with sibling-like camaraderie: healthy competition, but always supportive first and foremost. The label forged its own path overseas, putting on parties in London, Paris and other cities to showcase their artists and make an impact. With a lot of the international indie industry indifferent to trying to set stuff up, Pavlovic says: “We created our own vibe because it was hard to get in there and tour on somebody else’s.”

From there, more recognised music hotspots started to take notice. “By that point (07/08) we were kind of flying, so we’d had an article in NME like ‘world’s coolest label’ and shit like this,” Pavlovic remembers. Tame Impala, now probably Australia’s biggest act, Bang Gang, Canyons, Bumblebeez, Wolfmother (whose EP Daft Punk were rinsing on their Alive tour bus, according to Pavlovic), New Zealand’s Ladyhawke – whose eponymous album was another key 2008 release – and internationals, including Klaxons and New Young Pony Club, were on the roster. Others, such as The Whitest Boy Alive and Hercules & Love Affair, played the 2008 Nevereverland celebrating ten years of Modular. The label also released three ‘Leave Them All Behind’ compilations, which showcased their artists to the world.

“It was just a good point in time where a lot of us were able to do the things that we loved and we were all on a similar page about what we did love,” Pavlovic concludes.

He sold half of Modular to Universal in 2005 and his remaining share to them around 2015-16 after a legal dispute with the big label that involved money owed to Tame Impala. Pavlovic tells me he’s a ‘no regrets guy’ but the band being affected was unfortunate: “I was bored of it at that time, and it was time to move on, but maybe I should have just walked away from it rather than just let it implode.”

‘Shooting Stars’ by the scene’s new young guns Bag Raiders was released as a single in 2009, after being on an earlier EP towards the end of 2008, and their self-titled debut album followed the next year.

That track closed the shimmering era, as a new one dawned. Sweat It Out picked up where Modular left off, signing Rüfüs Du Sol and putting out their first two albums, as well as What So Not’s first release, which included a fresh-faced Flume. In the sleeve notes for the label’s 10th anniversary comp, released in 2018, there was a tribute to Ajax. Rüfüs - among artists, including Van She’s Nicky Night Time and Bang Gang’s Beni - noted the huge influence the dance legend had on them: “From as soon as we were legally allowed into Sydney’s clubs, it was Ajax who we’d go to see as often as we could. He introduced us to many of the artists who influenced the early direction of our band and he showed us how to truly hold and work a crowd. He signed us, believed in us and – with spooky accuracy – predicted a journey that has changed our lives forever.”

The Grammy-nominated outfit’s signing is tinged with sadness, Raeburn says, as it happened around the time they lost Ajax, who was hugely influential in Sydney and later in Melbourne, albeit in a different way, where he lived at the time of his death. He was integral to the scene that became what it did, was massively supportive of all artists, including those carrying the torch now, and even left a positive legacy on the way people talk to each other, Raeburn says.

A movement that began with the ripples of artists experimenting turned into waves after 2000, when the internet allowed these acts to find fans and be heard everywhere for the first time – Cut Copy unveiling ‘Hearts On Fire’ on Myspace before they’d finished ‘In Ghost Colours’. It washed over the globe, establishing communities of Australian artists in all the major hubs and made electronic music, live and otherwise, the norm. The golden age of Australian music may have peaked in the late 2000s, but Rüfüs Du Sol and Flume both getting a Grammy nomination for Best Dance Release at last January’s awards is just part of its enduring legacy. “The landscape now is massive and it was relatively small when we started,” Moyes says.

Read this next: Why Melbourne has become so much better for partying than Sydney

After several years in Europe, Whitford moved back home to Melbourne last year, undoubtedly one of the world’s great music cities: it’s got more live venues per capita than any other (Melbourne Live Music Census, released 2018). He doesn’t see why with the rapid growth of major Australian cities they couldn’t become the “new Berlin, or the new New York” in 20 years, as the world continues to become more connected. He’s always championed local music through Cutters Records, which put out ‘Oceans Apart’, a comp of Melbourne artists, in 2014.

“I never felt like the music being made say in New York, or in London, or Berlin was necessarily better in some way than what was happening here, and in some respects probably the music happening here was a bit more interesting. Because I think being geographically isolated, it’s a bit like how evolution creates these weird species that don’t exist anywhere else – it’s similar with the music made here.

“We get a chance to evolve our own weird stuff here in Australia and I think that’s kind of a special thing that should be celebrated and something people should know about internationally.”

Scott Carbines is the Herald Sun Real Estate's Digital Editor and a freelance music writer, follow him on Twitter

Listen to a playlist of 12 key tracks from the era below

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs