Scene reports

Scene reports

Music utopia is the mission for Oslo nightclub Blå

As part of Oslo World Festival, Blå Club brings African culture to a country that couldn’t be more different

“Norway is a free country populated by free people,” proclaims some white text scrawled on an old wooden sign hanging from the gargantuan willow trees over the Akerselva river outside Blå, a graffiti-laden club dedicated to emerging dance music cultures. Alongside Mela House, Khartoum Contemporary Arts Centre, Cafe Sør and the Nordic Black Theatre, it’s one of the most progressive spots in Oslo. Blå’s exterior walls are as motley and kaleidoscopic as the crowds and music that enliven its inner world – particularly on a string of frosty nights during Oslo World’s 26th edition. Blå’s bill is dedicated to artists who have come from South Africa, Lesotho, Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda and Somalia as part of Black Major and Nyege Nyege’s label nights, tasked with showcasing the work of their artists and their ability to translate their passion across any border, language barrier or societal boundary.

Blue and yellow banners adorn most of the city, proclaiming this year’s theme of ‘Utopia’: “an imagined place or state of things in which everything and everyone is perfect.” This writer has been tasked with hosting a panel for the festival called ‘Utopias Under Africa Skies’ and providing a DJ set that would somehow communicate my idea of a harmonious Africa and what that could sound like. I’m joined by Derek Debreu and Arlen Dilsizian, founders of Uganda’s Nyege Nyege Festival and label, along with their labelmates-cum-family Nihiloxica and DJ Hibotep.

The idea of an African utopia is often dismissed due to the widespread misconception that the continent lacks culture and the kind of organised society required. But the Oslo World events see artists introducing a new energy to the city that perhaps it didn’t know it needed. Despite – or because of – the continent’s battered and bruised reputation, African artists are now in the vanguard of new sounds and ways to experience themselves and their music, and Oslo has come to embrace them entirely.

Read this next: Festivals who support local scenes help dance music on a global level

It’s an interesting theme for a country known for its citizens’ high quality of life. Norway’s social safety net is world-renowned: almost everyone is well taken care of, with the country standing at a pretty utopian 9.4/10 on the Quality of Life scale. Compare, say, South Africa’s GDP per capita of $13,500 compared to Norway’s $71,800 and the difference in day-to-day life is palpable – particularly when a night out in the city centre more often than not begins barefoot in a nearby townhouse, wooden floors constantly heated to abate the Nordic chill. The use of Uber is discouraged in Oslo to protect the rights of local taxi drivers and to promote the use of the super-efficient public transport system. The clubs are a short walk away from each other, the safe cobbled streets filled with people strolling around at ease. But while the famed culture of Janteloven (putting society ahead of the self, reticence, and a reluctance to celebrate individual achievement) suits a cold and hostile landscape where cooperation is essential, it can also have its drawbacks.

“One of the biggest challenges Norwegian society has is that people can be very closed-off and struggle to express themselves, unless it’s to close friends or a therapist,” says Beatrice Kurmodzie, a Ghanaian-Norwegian singer-songwriter who goes by the stage-name AKUVI. “It’s a very socially awkward nation where people don’t speak to strangers because they’re so wrapped up in their own lives; of people born into wealth and stability, where the government makes sure everyone is doing OK, but people end up asking, ‘Who am I? What do I exist for?’ More often than not it seems to be people of colour who give you soulful, interesting and lively music. Spaces like Blå, Cafe Sør and the Nordic Black Theatre allow for people to be present, and expressive both on stage and in the crowd.”

Rutger Bregman’s book Utopia For Realists suggests that people who have everything they need to flourish are less likely to take risks or break away from any blueprints that keep them comfortable, and thus lose a sense of how they can be and do better. Art and expression suffer with no hardships to lament, no obstacles to overcome and no individual achievements to celebrate. Whether this is the case in Norway or not, the influx of other cultures entering the region, bringing new ideas and new experiences of struggle and maintaining self-love and internal wealth despite difficulty, seems to have benefited Oslo’s burgeoning music scene.

Svanhild Landvik and Marit Soldal have been booking acts at Blå since January 2018. The two also run a collective called KOSO CLUB with Piiksi and Hanneks; an artist-run, female-driven collective aiming to connect and strengthen femme creatives and club music. At Blå they’ve booked Shock Value’s Juliana Huxtable (USA), Lua Preta (Angola/Poland), Flohio and Yxng Bane (UK) Stella Chiweshe (Zimbabwe), FAKA (South Africa) and many more in the last year alone. ‘Everyone is welcome here,” says Svanhiild; “[we want to] show Oslo some of the best and most talented artists from around the world.”

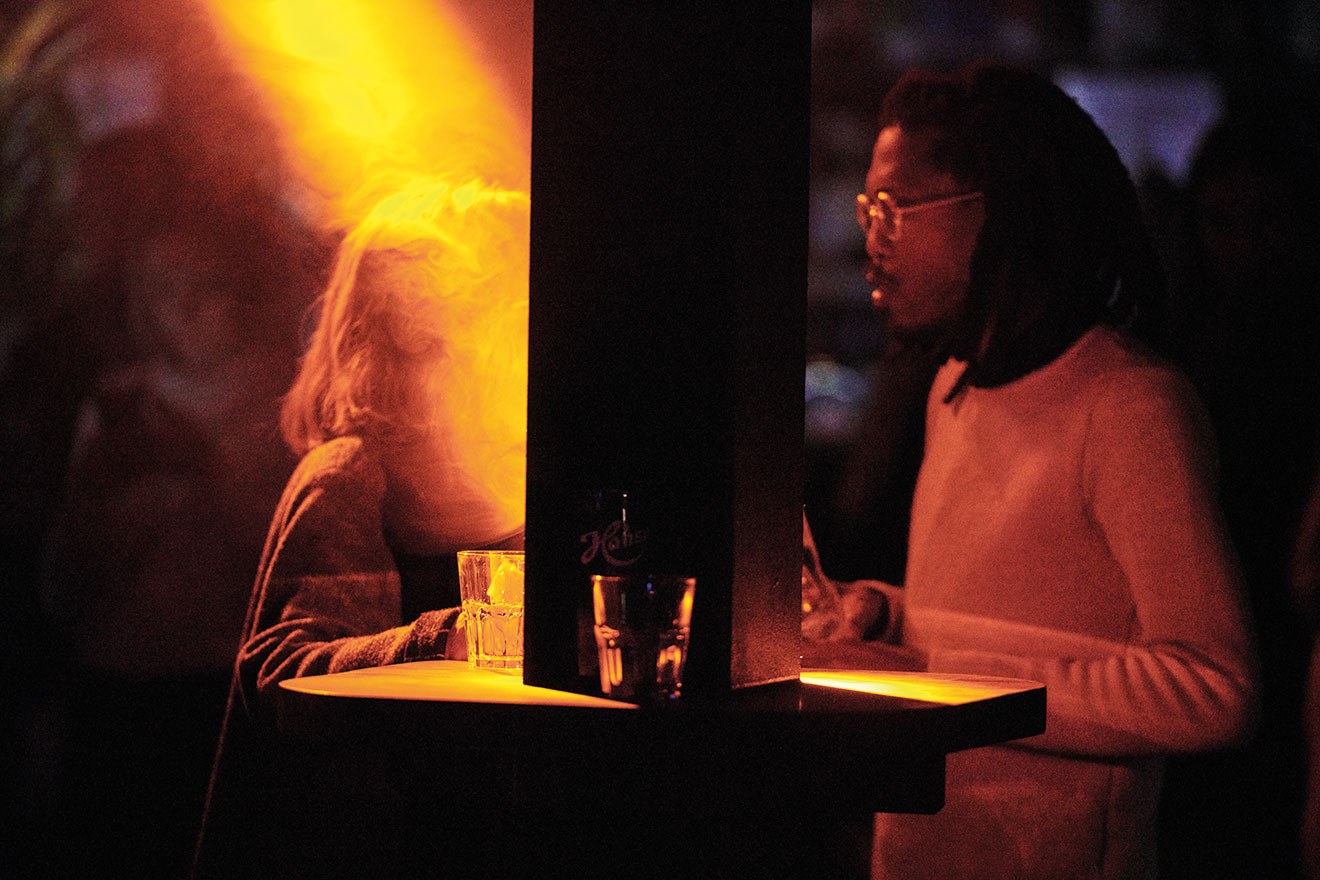

Looking out over over Blå’s crowd, we see red and purple floor lights falling on pools of people swaying back and forth. Hips and hands start to gyrate, at first a little awkwardly but later with a freer kind of spontaneity as the night intensifies. Spellbound by Nihiloxica’s fervent energy, the audience starts to forget… or perhaps to remember.

When asked how he bridges the cultural divide between himself and audiences unfamiliar with his sound, steely Ugandan lead drummer and MC Spyda replies without hesitation: “I don’t explain myself. I express myself. That’s what drumming is. We’ve reached a time where no-one can tell us who we are, and we decide what kind of Africans we want to be.” Even though two members of Nihiloxica are not Ugandan, Jacob Maskell-Key and sound designer PQ (Pete Jones) form a pivotal part of the collective for a harmonious and groundbreaking collaboration between cultures reminiscent of Blå’s ability to transport those present to uncharted worlds.

Read this next: Cxema parties are changing the face of the Ukranian techno scene

The past few years have seen Blå threatened with closure over concerns that the noise and rowdiness generated by its revellers posed a threat to safety. Thankfully the city’s residents came to the decision that this stronghold of nonconformist culture was a necessary location for preserving Oslo’s diversity. But maybe it was not just the diversity that its citizens were seeking to preserve; rather the friction between cultures and in turn, the warmth that difference can generate between people.

On the dancefloor, snaking dreadlocks brush up against ivory shoulders as Selasse’s remix of South African jazz legend Hugh Masekela’s ‘Stimela’ filters through the club’s PA. Stimela is the isiXhosa word for ‘hope’, and was originally written during a time when South Africa desperately needed equality, shared spaces and freedom. Today, braids and ’fros, kink and curl all in varying shades seek the same on every dancefloor in Oslo: to be the ‘free people’ that the sign outside Blå promises. It’s clear that everyone present, audiences and artists alike, believe that the way to utopia might just start with music.

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs