Features

Features

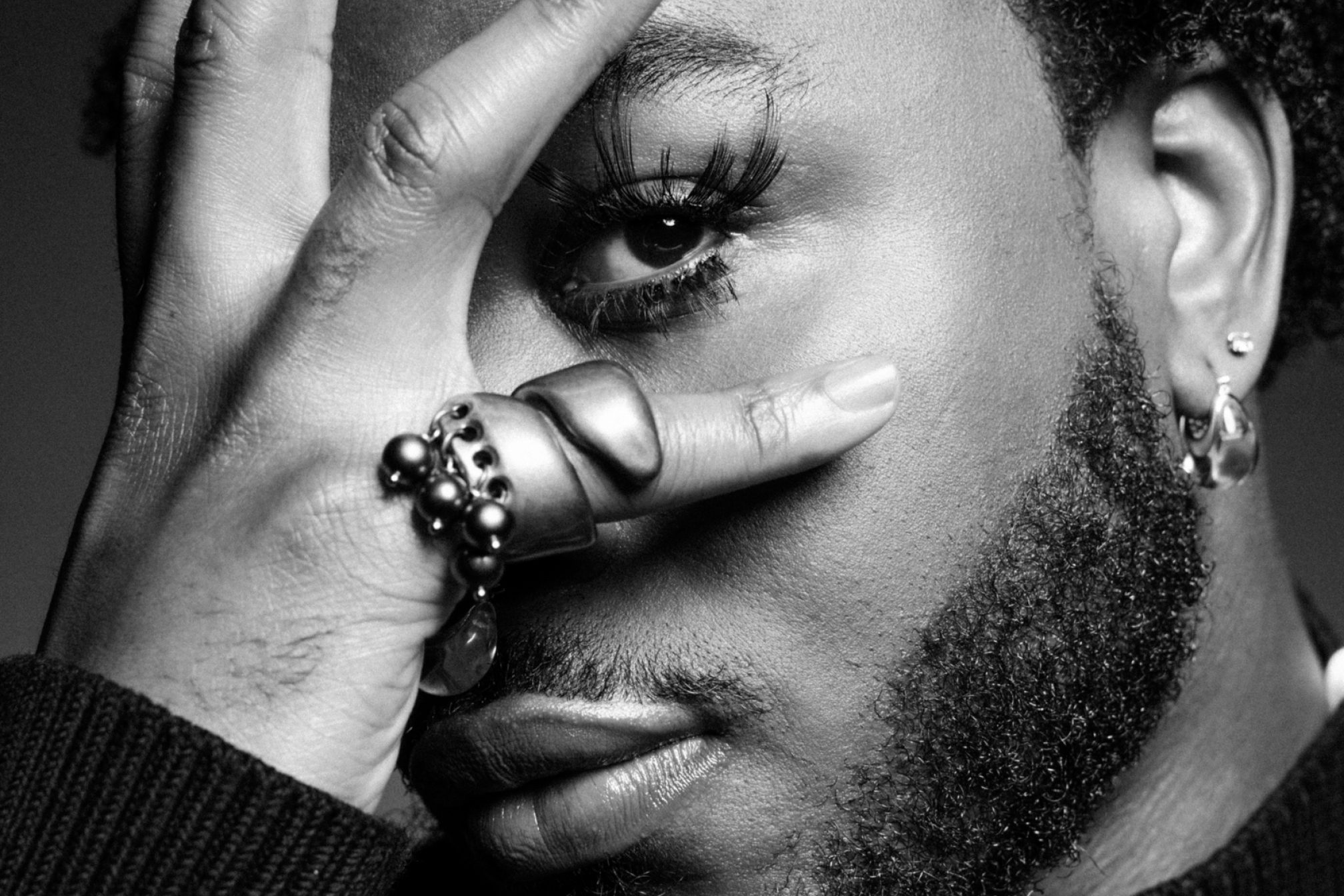

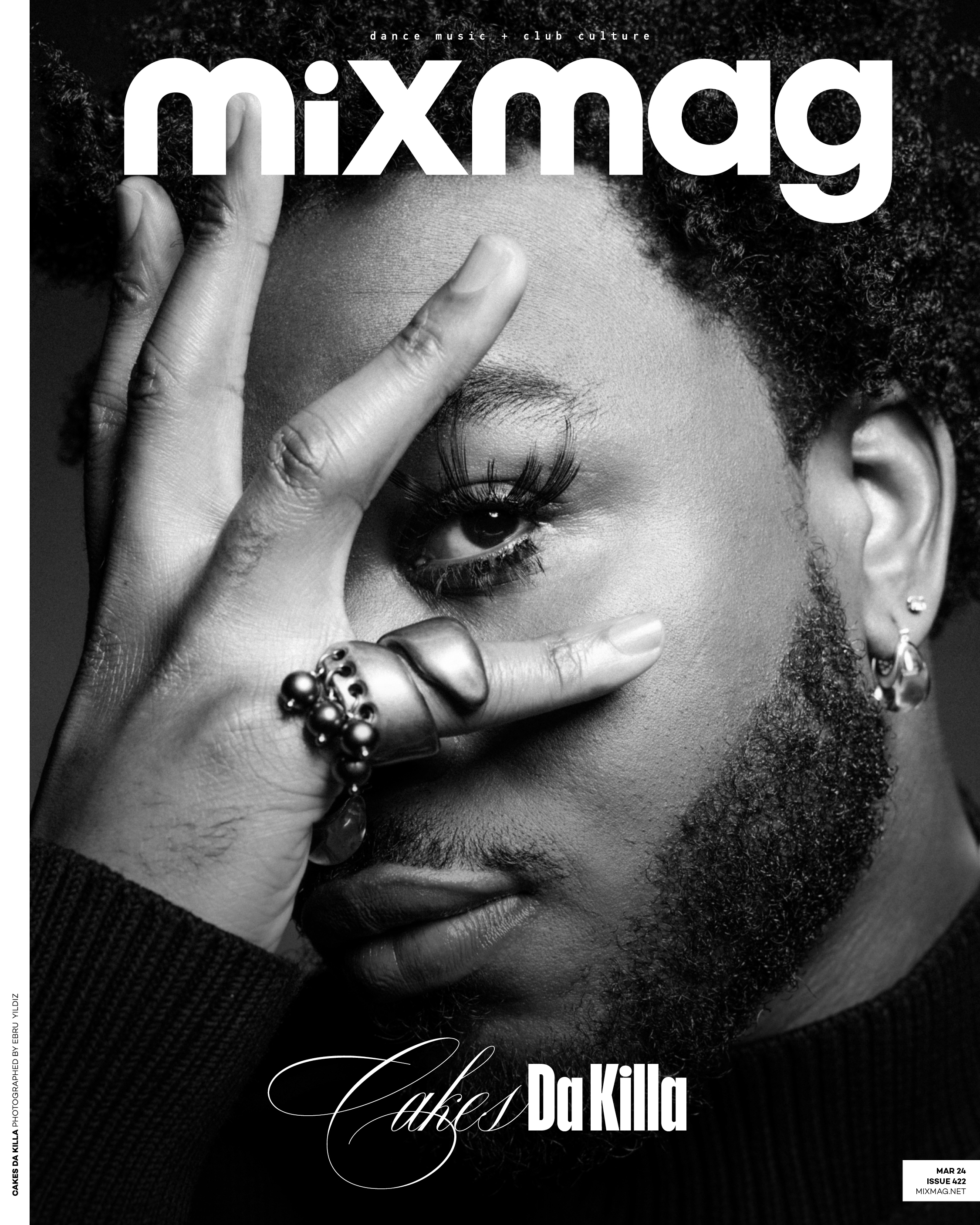

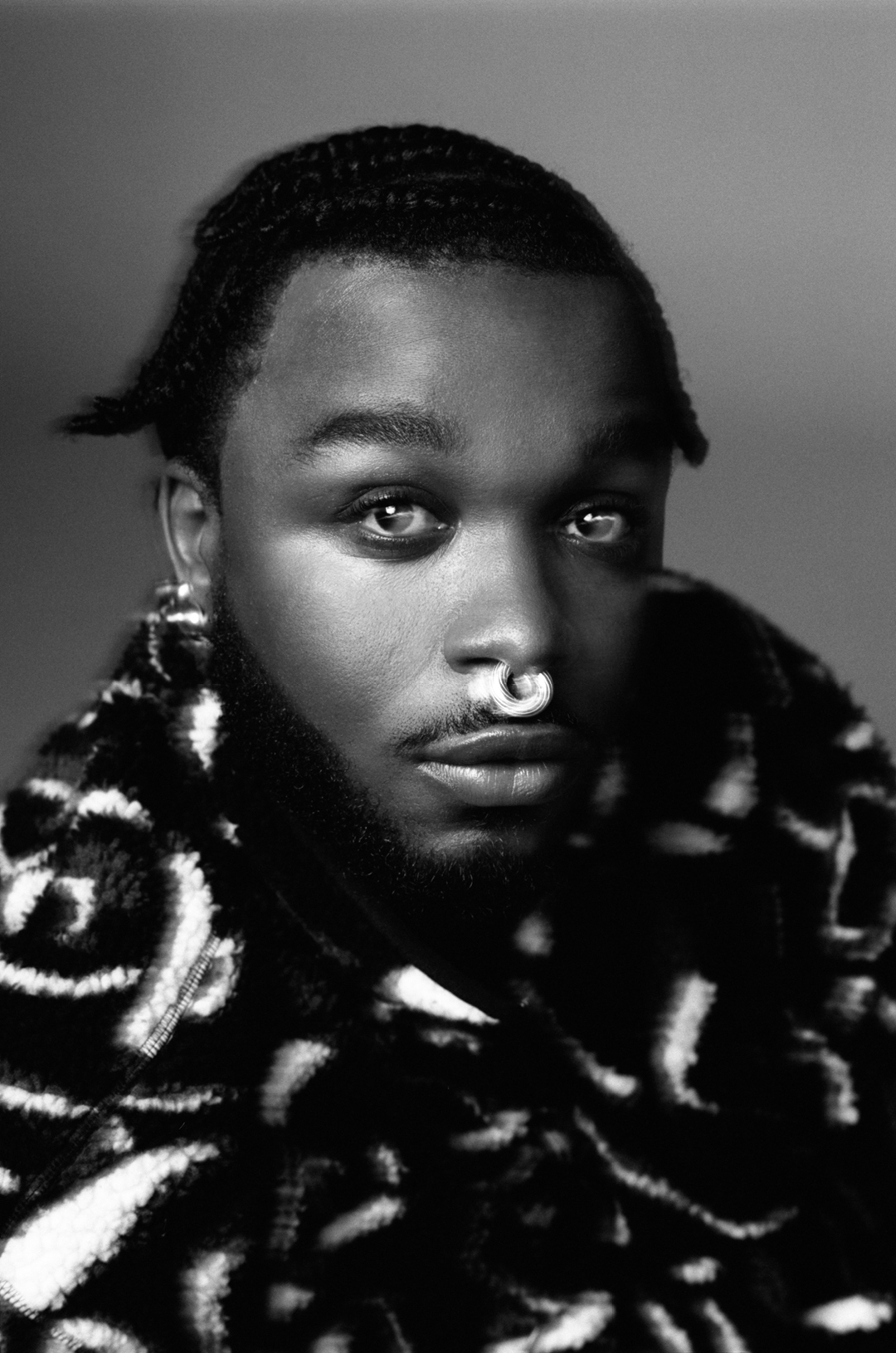

Poetry beyond the beat: Cakes Da Killa’s sharp songwriting is portal to his inner world

Inviting us on a journey into his inner worlds, Cakes Da Killa speaks to Tice Cin about finding a home within your village, the value of artistic taste and morals, and the allure of rabbit holes

Cakes Da Killa is a rap icon, a generational lyricist and songwriter who flips the club spaces and fault-lines of city-living with a surrealist interiority and sharp flow. Honed into prowess from a childhood writing poetry in the quiet bedroom community of Teaneck, New Jersey, Cakes, real name Rashard Bradshaw, always had his mind set on finding something more. From a young age he navigated his own feelings of being set apart from those around him, never really integrating himself into the landscape of the town he grew up in. “At that time, it wasn’t really cool to be the Black kid reading manga or writing poetry,” he reflects. Much of Cakes' musical influences started to form in those imaginative worlds. “I don't want to say I felt isolated, but I knew I was doing my own thing.” This level of assurance is how Cakes built a new world for himself.

“I was always gay. I knew that from a very young age. I came out in the third grade, so that already made me an ‘other’. I was always chubby, and I was always creative and artistic. I always knew I wanted to live in New York since I was a very little kid,” he says of his early memories. Aside from trips to see family in the areas of North Jersey where club music was popping the most, growing up in Teaneck felt far removed from that musical palette for Cakes. “It was a little whitewashed and boring there, if I grew up in Newark, it would have been different. Maybe I’d have made Jersey club.” It was this slight separation, however, that allowed Cakes to blend his influences gradually as a young person. Going to college in dance hub Montclair, and coming closer to different club sounds, Cakes was rapping in his dorm room between trips to New York. “I got small tastes of everyone’s different experiences of club and dance music, I was able to get that little taste of Jersey, and I could also get that New York flavour and that Philly flavour.” Exploration has always been key for Cakes, as soon as he graduated college he moved to New York in the late 2000s, “because that’s where all the weirdos were.” He proved himself time and again, freestyling in the back blocks of Brooklyn and securing reams of features with the likes of Honey Dijon and Rye Rye. Putting himself out there has always been an energising part of his process. “I wanted to go out and actively explore, because I know some people, they never even left home, they never go into the city. I was just like, I’ve got to get there.”

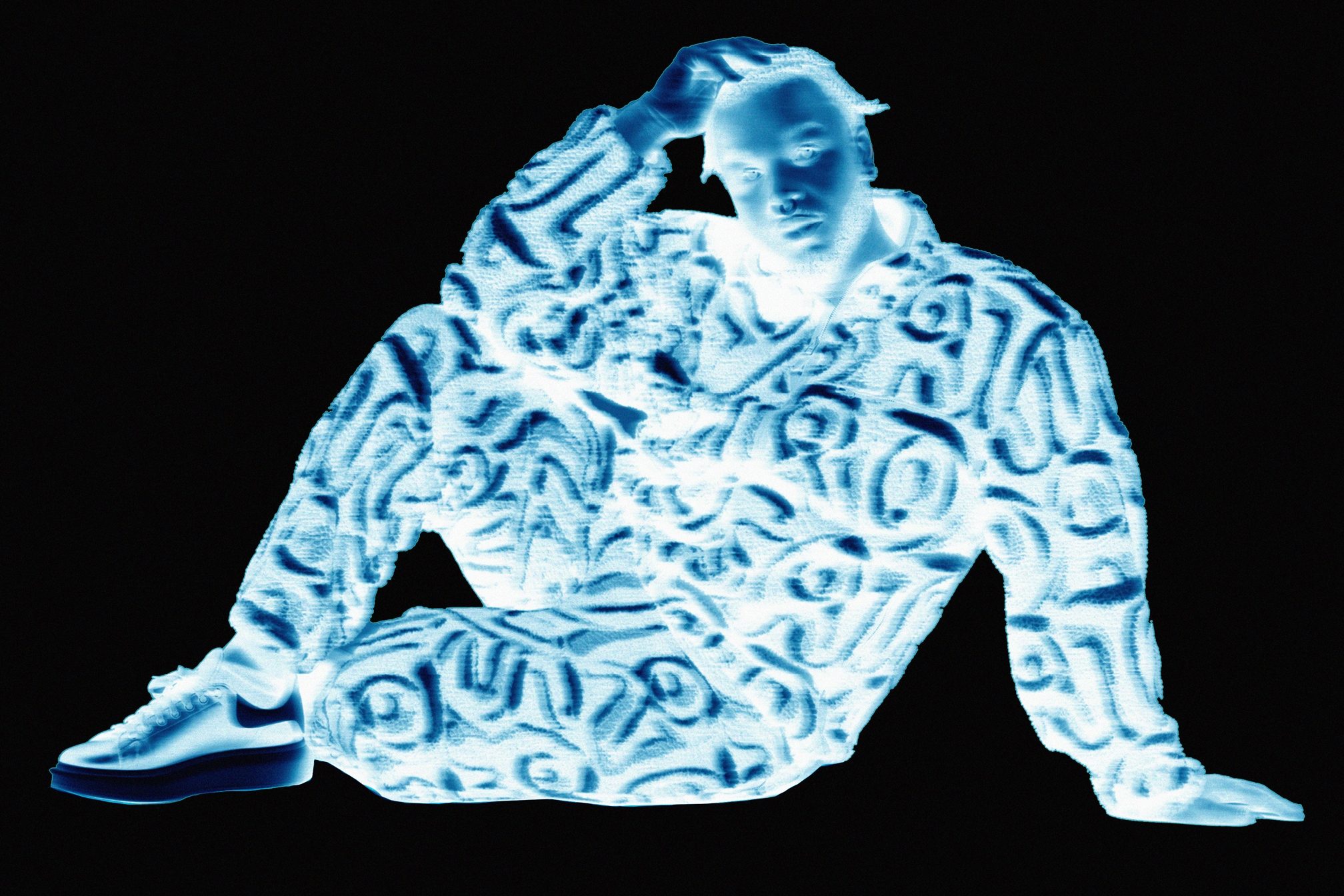

Fresh off a COLORS performance of recent single ‘Cakewalk’, Cakes has an electric energy as a performer, from touring Europe and rapping in the crowd of London’s Camden Assembly Hall in a sailor’s cap and skirt, to intimate after-hours sets in New York’s underground party scene. Newark community activator, the house and Jersey club stalwart Nadus, shares his first experience encountering Cakes live:

I remember the first time I saw Cakes perform at a Cunt Mafia event on this quiet block. I think it was Johnson Ave in Brooklyn at this random warehouse with these dark red lights. The event was dope but the whole night changed when Cakes performed. The energy in the room shifted. The more I would go to an event he was at, that became the status quo. That first night I introduced myself and naturally shared that I was from Jersey, Cakes saying “me too!” made those bars, those experiences and those shows special. A young, Black man like me, from the state of New Jersey, killing it. It's been dope seeing the different versions and sounds and visuals of Cakes, and him being his full self through all of it. You talk about NY rap to me, he's one of them ones...you talk about Jersey rap to me he's one of them ones.

Cakes’ new album ‘Black Sheep’ with long-time collaborator Sam Katz, the producer behind 2022’s ‘Svengali’, is a tour through his own amalgamated city on his terms. It emphasises the rapper’s ease within in-between spaces, comfortable with the idea that Inside and Outside are two different psychological territories that his music is always moving between. The whispered refrain of “black sheep” in ‘Downtown J’ feels like windy subway staircases, curling us towards neo-noir songs like ‘Cakewalk’ that move between poetry in formal verse and Cakes’ hissed rap flow. Earlier in the project, the chilled and sexy ‘FourPlay’ is a breathing link, a batida-inflected charmer that makes you imagine lovers in seduction. In a similar vein to his 2014 track ‘Truth Tella’ ( featuring the bars “posted up with my papi, eating salt fish-ackee / known for waxing the kitty, I call him Mr. Miyagi”), Cakes writes with lavish viscerality, not too shy to let his listeners behind closed doors as he pushes the dial with his linguistic flair: “I open the doors like he’s the tight lock”. The pride on his face is apparent as his smile widens when asked about his new album: “I've been sitting on it for a while, so I'm happy it's finally able to be out in the world. I think what I love most about it is that it's the most me project. It combines all the things that I love sonically. I think it's very honest. I'm always proud of the work I do, but I'm happy that I was able to actually put out a project that covers all bases for me.”

Growing up, Cakes was obsessed with fighting games, especially Tekken, Soulcalibur and Street Fighter. “We always wanted to be the woman character and whip some ass. That's the gay trope!” he laughs. The production on ‘Black Sheep’ cut ‘Crushin in Da Club’ has an 8-bit game meets hookah lounge energy, with Cakes revealing: “Sam Katz made it like the Lowrider soundtrack.” Similarly, on Cakes Da Killa’s 2014 project ‘Hunger Pangs’, Sam Katz’s mix of his song ‘Truth Tella’, produced with LSDXOXO, also has that gaming influence, seemingly spliced between Soulcalibur and Pokémon’s creepy Lavender Town theme. These soundtracks formed a psychological lodestar to Cakes over the years. “Even the loading screens stick with you.There's a game series called Marvel vs. Capcom, and they have a very crazy score that's really in my psyche. Those memories can influence your tastes without you even noticing,” he says. “When I listen to ‘Black Sheep’, I do hear little bits of every one of my old projects on it. That's because I write all my own music and I pick all of my own beats. If you listened to the project from top to bottom you could hear it like a retrospective.”

Cakes developed as an artist in a highly online era, heavily on the likes of AOL and Myspace, and he’d write to instrumentals then post them on Facebook. He came of age when being online was more of a social experiment. “People only logged on to computers to Google a question, we slowly made our digital communities,” he recalls. Online was just a space for you to keep in contact with your immediate circle, or your scene, or the town you were in. “Now you can be in contact with the entire world in some of these spaces. And now companies have put more presence on it and you have to deal with algorithms. Online has always been scary, but it's even more scary now. Myspace felt so innocent, comparing a Myspace bulletin to a tweet for example, a tweet could start an actual war!” Simultaneously, he stresses the importance of online communities for maintaining spaces that are part of counterculture or not considered mainstream: “We need to tend space for that, too.”

Read this next: Video games are influencing a generation of electronic innovators

As an independent artist Cakes Da Killa has worked across many labels, like HE.SHE.THEY, Stixx’s Downtown Mayhem, Venus X’s GHE20G0TH1K RECORDS, and Classic Music Company. “The artist that I was when I was working with Hot Mom USA is definitely not the artist that worked with Classic or HE.SHE.THEY, because I'm constantly evolving, and experiencing so much in life. There are certain things that will be staples in my sound, which I think if you're a fan, you would pick up on,” he says. To Cakes, growing as an artist requires learning the industry, which is constantly changing, and knowing that every label handles artists differently. The lessons are well spent. “That’s why I'm able to be in label situations now and know exactly what I want and what I don't want, and what works for me, and what doesn't.”

As with many people operating across the music industry, Cakes Da Killa has dealt with a lot of fuckery in his time. “Oh, so much fuckery. Fuckery lessons!” he exclaims. “It comes with the territory. But that's why you have to not be desperate to be in too many situations. Which sucks, because sometimes you just want it to make sense and you want it to just work, but sometimes you have to say no or you have to lose out on opportunities.” There has been a safety net of sorts for the highly motivated rapper, as he gratefully acknowledges that features and gigs have given him the ability to have more options. “I've been able to be a touring artist for the better part of a decade, not a lot of artists could say that. I don't take that for granted. I'm constantly being asked to collaborate with people, and I'm able to turn down a lot of things, but that's not out of ego, that's just because I'm so particular. Learning the game means learning that you can't always be in every room.”

Shy of the potentially gatekeeping connotations of the term “protecting culture”, Cakes feels there’s a good way for people to engage with scenes outside of their own, like ballroom culture. “There's a way you can experience culture and pay homage to it or actually work within the culture and be a part of it.” He highlights his producer Sam Katz as the type of collaborator who really gets it. “Sam Katz is a white male who's done my last two records. But to me, Sam knows he's a white male and he's operating as a white guy. He's not masquerading like, ‘Oh, I'm in New York, so let me go to a ball and make a ballroom beat.’ A lot of producers have that kind of conquistador energy about themselves.” While he feels inspiration shouldn’t be policed, he has noticed a pattern. “I think people be biting…they be copy and pasting things that shouldn't really belong to them. A lot of the times my only reservation is, please don't send me anything that says ballroom, if you're not in ballroom. Don't send me a bounce beat - I get a lot of those - if you're not actually in New Orleans. I don't want to be attacked by someone, even in my own community, saying: ‘Bitch, why are you appropriating?’ Or: ‘Why are you working with someone who's appropriating?’.”

Read this next: Voguing: A Brief History of the Ballroom

The balance between personal cost and values has been a mainstay in his career. Cakes once had an opportunity to do a song for a commercial and his client wanted a bounce song. He responded: “I don't make bounce, but I want to take the opportunity.” He brought in a bounce artist to make it more valid and in reply the client went cold. What happened next? “It ended up being a fucking Super Bowl commercial!” he exclaims. And the artist that ultimately took it on was not a bounce artist. “That was good for them that they got the opportunity. But I just know for me, my artistic morals are worth way more than a cheque. I knew if I did a bounce song and that shit was in the Super Bowl, Big Freedia is going to cuss me out! These are people I know personally. You're going to see them around, they're going to be like: ‘Bitch, what are you doing? There's a bigger price on that.’”

In his early twenties, Cakes was making more money than he realised, to the point where he didn't have to get a day job as an adult until the pandemic. Prior to that he was constantly doing features and touring, and he always put 100% into his live shows. “It didn't have to always be a sold-out, packed audience. Sometimes, if it's 12 people in there, one of them is a promoter that works at another venue, and they like what they see,” he says. Money didn't become a thought until he couldn't make it from performing and features anymore. He needed to start thinking about himself more as a business, a transition from eccentric artist to something more. “Once you get to a certain age, you have to figure out how to fuse the artistry and the business in a way that makes sense. You need to continue to sustain it if you want to do this forever.”

Going back on tour after it ended was a nerve-wracking choice for someone who had only just adjusted to a new rhythm of nine-to-five work. “I got used to that way of hustling and it took a lot out of me to convince myself to return to touring post-lockdown,” he reveals. Ultimately, the sheer love of performing took him back: “That crowd interaction and that exchange of energy with people makes me feel like this is what I'm supposed to be doing.

Cycling back a little bit to 2015 when Cakes dropped the ‘#IMF’ EP – moving with Minnie Riperton samples and lyrical explorations of love and loss — it shows another part of his artistry. There are parts of ‘#IMF’ which could ring bells for listeners during the pleading vulnerability of ‘Black Sheep’ track ‘It’s A Luv Thang’ ft Wuhryn Dumas or the relationship with distance in songs like ‘Problem 4 Problems’. Isolation is a recurring theme within his music. “I do a lot of things alone. I travel alone. I write alone. I do a lot of things alone. That feeling is the vessel that holds a lot of my inspiration,” he says. There’s a duality to Cakes Da Killa in this regard, as someone who also loves socialising and being outside. “I think those moments of unplugging and just downloading and processing things are very important,” he says. “I think that that's why my work is so wordy. It's not until recently, listening back to some of my earlier music, where I'm like, a lot of this is not really a record, it's poetry on a beat, where I'm not really thinking about it. I'm just writing what I want to write.”

The free-flowing verse that encapsulates so much of Cakes Da Killa’s music, especially his earlier songs, comes from writing poetry in his childhood. Back then, he says, “all the rappers would respond to the question ‘how did you get into writing music?’ with the reply, ‘poetry’.” For Cakes, it always started with the word. “I always have to edit myself. I'm too wordy, too, too wordy. I love that though,” he says. He feels like that's what's missing in the current musical climate. “Most rappers now, when you ask them what they like about music, it's never the word or the poetry. It's ‘I want to make a bag’ — which is also cool. I think you need to also have that drive to be able to get your money because the industry will play you. But I do feel like the lyrics and the music are the two parts that make music. If you don't have an appreciation for either one of them, what are you doing?”

‘Don Dada’, Cakes Da Killa’s recent collab with NY producer Proper Villains, was used in the trailer for the film Femme about a drag performer whose career is affected by a homophobic assault. It has a darkness, different in tone to his own video for the track, a bright and flirtatious 1970’s style strut through city rooftops, where Cakes plays an eccentric photographer in a curious exchange with his model-spy, Bidi, exploring the power of Black gazes. When people hear his music through syncs, and they interpret his music within a different context, Cakes loves it. “I was really honoured to be included within the rollout for Femme, even just that smaller moment. I love any opportunity where people could reimagine anything that I do because I think it continues the conversation of the work (outside of just being compensated).”

Getting older and growing in himself, Cakes has started to realise the immediate world he lives in is “actually shit.” A lot of this is his experience of being American and processing a lot of the hypocrisy woven into society. As a Black queer person he has “always been othered. But to even just see that people really don't give a fuck is disheartening.” As a child writing poetry, reading manga and imagining what the future would be like, he thought we would be living “in a more futuristic, idealised, fantastical way by now. But people want to regress. It’s sad that we don't really value human life or the planet.” It can be overwhelming for him to even think about sometimes. That’s why talking with friends and using music as a form of escapism helps him. “Escapism means everything to me because that's what I used to survive being a young queer Black person,” says Cakes. He also hopes by making music that “people who are dealing with an overwhelming lot can listen to a record of mine and maybe feel some type of comfort.”

‘Black Sheep’ reinforces the regenerative quality of that escape and resilience. In the training grounds of his early years, he was reading, watching movies and listening to albums front to back (“which no one seems to do anymore”) and it kept him anchored. “Before we even had that type of language to know that it was escapism, escapism gave me the skills to develop the armour that I needed to face the world,” he says. It gave him the understanding that he could create his own world. Before high school je’d never wanted to be a recording artist, but interactions with friends who were dancers and singers - the first creative people he became close to - showed him a path to walk out onto. “I would say that that's what gave me the nerve. It does take a lot to just move out of state and decide you're going to be this person. Most people don't do that. Most people are not even themselves in their regular day to day,” he says.

Moving to New York was a spiritual and symbolic shift for Cakes Da Killa, but this came with its own caveat of misconceptions, which he alludes to when asked about how it feels to be considered a New York rapper. “I don't think that the New York thing is the issue. I'm more hung up on the New York rapper thing, because that comes with a certain connotation,” he says. “Whether or not I claim wherever I’ve been, I never was that person to be like, ‘oh I'm trying to put New York on a map’, because it has already been so influential to me. I know the native New Yorkers hate us transplants. But so much of New York culture is made by that.” On the flip side of the coin, people from Jersey who now realise Cakes is one of their own will ask, ‘why don't you claim Jersey?’. “I do get it because there are a lot of people who are false flaggers in that sense. My story is my story, and that's what it is. I’m nomadic. There's no shame in my game.”

In ‘Black Sheep’, it feels like we're seeing the world through Cakes’ eyes. We're seeing clubs and nightlife as church, but also, the smoking area and other liminal spots, as the ‘Mind Reader’ video explores so well. The atmosphere and the psychology of queer spaces “means everything” for Cakes to capture in his writing. “Because that's where I blossom. That's where a lot of my inspiration comes from. I go to these places to be inspired. I go through these places to hook up with people, to mingle, to socialise, to worship,” he says. Putting vignettes of these spaces into his albums is his way of giving the reader that experience. “I want them to be put in a world because that's how albums used to feel to me. You were in the artist's own landscape. Music from a more cinematic kind of point of view.” Sonically, he glows with joy to outline that his collaboration with Sam Katz is what enhanced the immersive quality of ‘Black Sheep’. “A lot of the world-building is Sam putting in his own taste to it. It's a blessing that he and I have similar intentions, we push each other forward and we challenge each other and it always ends up working out.”

Having written about going down rabbit holes a fair bit, it’s easy for us to get sucked into talk of different dimensions. “Portals are cool depending on where they go. I love rabbit holes. I was just talking to my friend who did this doula retreat in Ecuador, and she was talking to me about her spiritual experiences. Those are always good portals and rabbit holes to go down,” Cakes say. That’s also why he loves history. “I'm such a history buff and I'm always trying to ask why and doing more research on different things. But that could end up having you watching a documentary on Hitler's weird sex life. That's the nerdy-ism in me.”

If he could take someone to an alternate dimension of his choice, it would be to Atlantis. “Are Black people allowed in Atlantis? In my Atlantis they would be. There's interesting folklore about slaves, how from one of the ships, slaves were tossed overboard into the water to drown them, lost to the water, and ended up becoming mermaids. Drexciya, that type of folklore.” Cakes finds this mythology very romantic, because of his belief that water is spiritual and cleanses you. Less virtuously, going through the rabbit hole is an invitation that became more apparent when he started drinking alcohol: “That's what kind of made me more of a partier, going off to another universe…”

Read this next: Mysteries of the deep: How Drexciya reimagined slavery to create an Afrofuturist utopia

Entering into his world, the ‘village’ and queer community spaces where he feels understood has brought about some of Cakes Da Killa’s favourite collaborations. “Those experiences and relationships have happened naturally based on them being the village,” he says. Collaborating with queer people of colour makes the conversations go quicker. ‘I don't have to play catch up. Sometimes when I'm working with people (and that's not to say that they're not qualified to do it), they might look at me and assume, ‘gay rapper, OK, for this music video, we'll do Paris Is Burning. That's already been done. Let's think more Hype Williams, or let's ask each other, ‘have you seen the movie Taxi Driver?’. Sometimes you have to explain yourself outside of the box that society puts you in” he asserts.

The effervescent rapper has been attached to so many different waves over the years, but lately things have felt different for Cakes Da Killa. “I don't think I have that in the same way anymore, which is why I think the album ‘Black Sheep’ came about, because in my mind, I would have loved to be in a group. I love collectives. I don't love group projects, but I love group dynamics — I don't like dealing with egos though. Collaboration across the board is great if it's done right. As of right now, it's me and Sam.”

A fully hands-on artist who has essentially creatively directed his whole career, it doesn’t come without the risk of burnout. “It’s exhausting. Exhausting. Exhausting. But it's rewarding,” he says. This isn’t about control, Cakes is comfortable with delegating to a team, it’s about due diligence. “When you are the life force behind something, sometimes people look to you to give final say on everything, even things that you really don't care about. I’ve put myself in that position based on my work ethic, so I don't complain. I value that position because I am very particular, and I think I have to be particular because I want to be here for a long time, and I don't want to do anything or put anything out that I don't like in the future.” He likens his process to looking at a baby picture of yourself, and wondering why your parents put you in a strange outfit but you can still appreciate it for that moment. His journey as an artist has taught him to be particular with, for example, the makeup he might have on at a video shoot or his styling. “I always have to keep on it, because a lot of people only want to dictate to their artists. Some artists need that, but I don't think that that makes you an artist. You need to be informed, and you need to have some type of taste and viewpoint and perspective. Ask, what are you a vessel for?”

He emphasises that there’s space for everybody, but he also wants better for everybody. “There needs to be another side to fluff music if people want to have a different experience. I don't think fluff music's bad, but that shouldn't be the main sound,” he says. The viewpoint of ’Black Sheep’ has an evolved grit to it, with bars like “I lay my verses down cleaner than you lay your lace” in ‘Problems 4 Problems’, an elevated aggression to projects like ‘Hunger Pangs’. “This is the first project I'm doing where prior to its release everyone already thinks I'm such a mean girl, actually, now I'm going to be a mean girl,” he asserts. In a music and cultural landscape where many cultural muses have the same stylists and choreographers, it can be hard to feel like artists in the mainstream public eye are offering variety, from the content of their music to their aesthetics. “Got the same wigs on, you all got the same belt, and it's insane to me,” says Cakes, leaning into this with gently instructive passion. ‘As a creative and as a vessel, you should have a viewpoint. Janet Jackson and Madonna could both wear a Jean Paul Gaultier dress. They're not going to wear it the same. Be a different moment! A lot of people don't want to have the input, I do get it, it's hard. I feel like that comes with the job of being an artist though, to present something that's unique or fresh.”

On a mission to better present the sonic aesthetic of his music through bringing his live shows “up a notch”, Cakes says, “that's my favourite form of presentation. I'm going to make sure that I'm constantly levelling that up. For so long, I was happy to say ‘let’s get a couple of dancers, let's put on a good show, and have a little comedy’. Now I'm like, ‘bitch, let’s get the choreo situated. Get the VJ situated’. For this next tour, I’m investing more into my live presentation.”

Above all, Cakes Da Killa wants to be received by the public as a songwriter. The features on ‘Black Sheep’ - Dawn Richard, Wuhryn Dumas and Stout - performed to lyrics written by Cakes, a collaboration that was affirming and surreal for him. “I know that in my core, I'm a songwriter, because it moves me so much to just hear someone interpret my lyrics. It makes me feel so fulfilled,” he says. He’d previously had opportunities to write for artists including MARINA (formerly Marina and The Diamonds), who approached his manager requesting a writing session. The collaboration wasn’t able to become fully realised but it was still a turning point for Cakes. “That was so amazing to me because not only did I feel like, ‘wow, somebody's actually seeing me just for my talent’, it made me know that I'm good enough to be in those rooms. Those types of situations, and they've happened here and there through the years, those are always the best, because sometimes with the media, they make you feel like you're only enough for a box, and then you're just like: ‘No, bitch, I'm talented.’” Deciding to adapt his albums so that they’d also serve as a songwriting demonstration has helped him to find a way to share in a climate where getting into the songwriting game can be difficult, especially if you don’t live in LA.

Cakes is effusive about how the right collaborations can make a record. “They did their own ad libs and all that. I was singing off-key to this track that I’d written, and then they redid it, and put their spin on it. To hear Dawn sing my lyrics, to have Stout and Wuhryn just interpret a concept that I wrote is insane to witness,” he says. The matches made natural sense: Cakes had been a fan of Dawn, who came of age on the reality show Making the Band, since the beginning. She’d always been in his pop culture psyche. They crossed paths because they had the same management at the time, and right before the pandemic, they did a show together. Both artists, who were considered alternative (“because we're Black artists who don't make strictly hip hop or R&B, which is stupid, because all music is Black”), soon realised they had been mutual fans of each other. Another time, at a bar, post-lockdown and feeling fully outside, Cakes met Stout. “I'm obsessed with Stout's voice, and I knew she would do exactly what I needed her to do on this record, because she has that churchy vocal. It’s not strained (which is also a cute way of singing), but for this record I needed a powerhouse. I need singing from the bottom of your feet.” Wuhryn also has that raw talent of “being able to sing down and riff down”. They met “in this community, which is why I'm so pro going out, because you never know who you would meet at a bar. If I hadn’t met Stout at that bar, we might not have been able to collaborate.”

Having previously said that rapping was initially his way of making fun of straight dudes, it’s plain to see that Cakes Da Killa is a genuinely funny person. The wordplay in his bars are fun with their risk, like in ‘Svengali’ when he raps: “I’m celibate because none of you f*ggots can top me”. Humour and truth overlap for Cakes. “See those little things with the celibacy metaphor? Those are the nerdy-isms in me that I think people don’t do in rap anymore,” he says. Citing influences such as Busta Rhymes, Missy Elliott and Ludacris, he shares: “Technically, I could be considered a very serious rapper, people say I rap-rap. I'm serious about the art form, but I don't take myself too seriously to be playful, because I'm not a conscious rapper. There’s still a little humour.”

In the New York episode of his two-part BBC radio documentary The future of hip-hop, Cakes went back to interview radio host Peter Rosenberg, 10 years after their Hot 97 interview on Ebro in the Morning. That interview focused on a lot of what Rosenberg referred to as “being ignorant for the purpose of learning”, and let’s just say little to no questions were asked about Cakes’ music and his poetic lyricism, his thoughts on the ballroom scene, or any of the landmark collaborations he’s had over the years. Overheard in the background of their BBC interview, just before the official conversation begins, you can pick up Cakes joking about tables turning (a stand-out theme in ‘Black Sheeps’’s ‘Ain’t Sh*t Sweet’ too!). It’s a palpable moment. “Ebro and Peter have always been very supportive of me in their own ways. I think people looking at that Hot 97 interview now kind of are like, ‘oh, my God, the Hot 97 interview was so bad’,” Cakes smiles. “I didn't consider it that bad because that's the type of conversations you would have with people who weren't queer at that time. So to me, I'm just like, ‘OK! Let me break it down for you.’ But seeing him after that, for the BBC interview, it was very fulfilling because I was happy that I could be interviewing him and showing people, ‘look, I'm still here. Isn't this so crazy?’”

‘Black Sheep’ is out via Young Art Records on March 22, pre-order it here

Tice Cin is a freelance journalist, follow her on Twitter