Features

Features

Cerrone's contribution to dance music is as important as Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk's

The father of euro-disco has sold over four million records during a 40-year career

In the era of Extinction Rebellion, climate change and climate denial, is there a more relevant song than Cerrone’s ‘Supernature’? Written and produced in 1977, its lyrics about nature wreaking revenge on man’s misuse of the planet have never seemed more apt – “maybe nature has a plan, to control the ways of man” – so it seems apposite that we’re talking to the man behind it on a balmy, global warming-assisted morning. Our encounter is a battle between what Cerrone describes as his “fucking bad Engleesh” and our laughably rusty French – though we eventually settle on the international language of Parisian cafes, Franglais.

To younger readers, Jean-Marc Cerrone may well be one of the greatest dance music producers you’ve never heard of. He’s been sampled hundreds of times, from rap giants Beastie Boys to the Avalanches and Groove Armada. Speak to any member of the modern generation of French producers, from David Guetta to Dimitri From Paris and Daft Punk to Bob Sinclar, and Cerrone’s music was and is a primary source of inspiration. Goldfrapp even named an album after one of his songs.

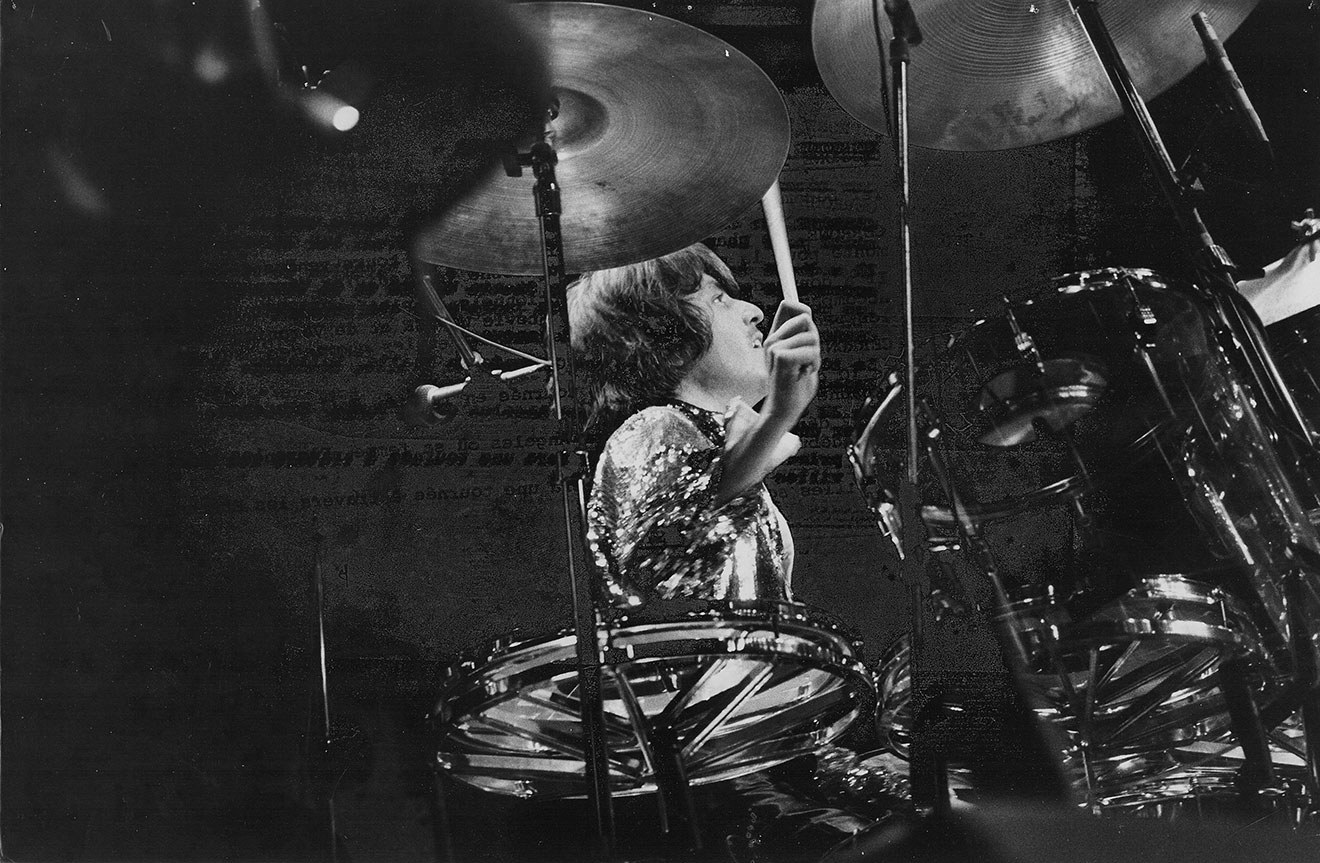

If Cerrone didn’t invent disco with his debut single ‘Love In C Minor’, he certainly brought to it a European swagger and a kick-drum the size of Bordeaux. “I’m a drummer. So when I decided to record ‘Love In C Minor’ I put myself right in the front, OK? This was one of the reasons nobody in France wanted to sign the track: ‘Why are the kick-drum and bass so up-front? Can you remix it?’ I said, ‘No, I’m a drummer. It’s normal for me. I put my instrument – the drums - right in the front.’ It was the heart of the record.” The fact that the track was over 16 minutes long can’t have helped it find a deal, either.

Read this next: 10 early-80s post-disco tracks that helped inspire house

An exasperated Cerrone formed his own record label, Malligator, and pressed 5,000 copies of the single. After a mix-up at a record store, 300 copies found their way to New York, where it blew up. US deals and adulation swiftly followed. His productions, with monster kick-drum and analogous bass, became the shoulders upon which most of dance music’s subsequent recordings have stood: rhythm over melody. Alongside Giorgio Moroder, he brought Europe to the disco. Yet he always managed to retain much of the r’n’b grit and sparkle that spurred him on originally: “I was influenced by Barry White’s string arrangements,” he says. “The brass and really special harmonies on Chicago’s records, and the wah-wah guitar from songs like the theme from Shaft. It was definitely American productions that influenced me more than anything else.”

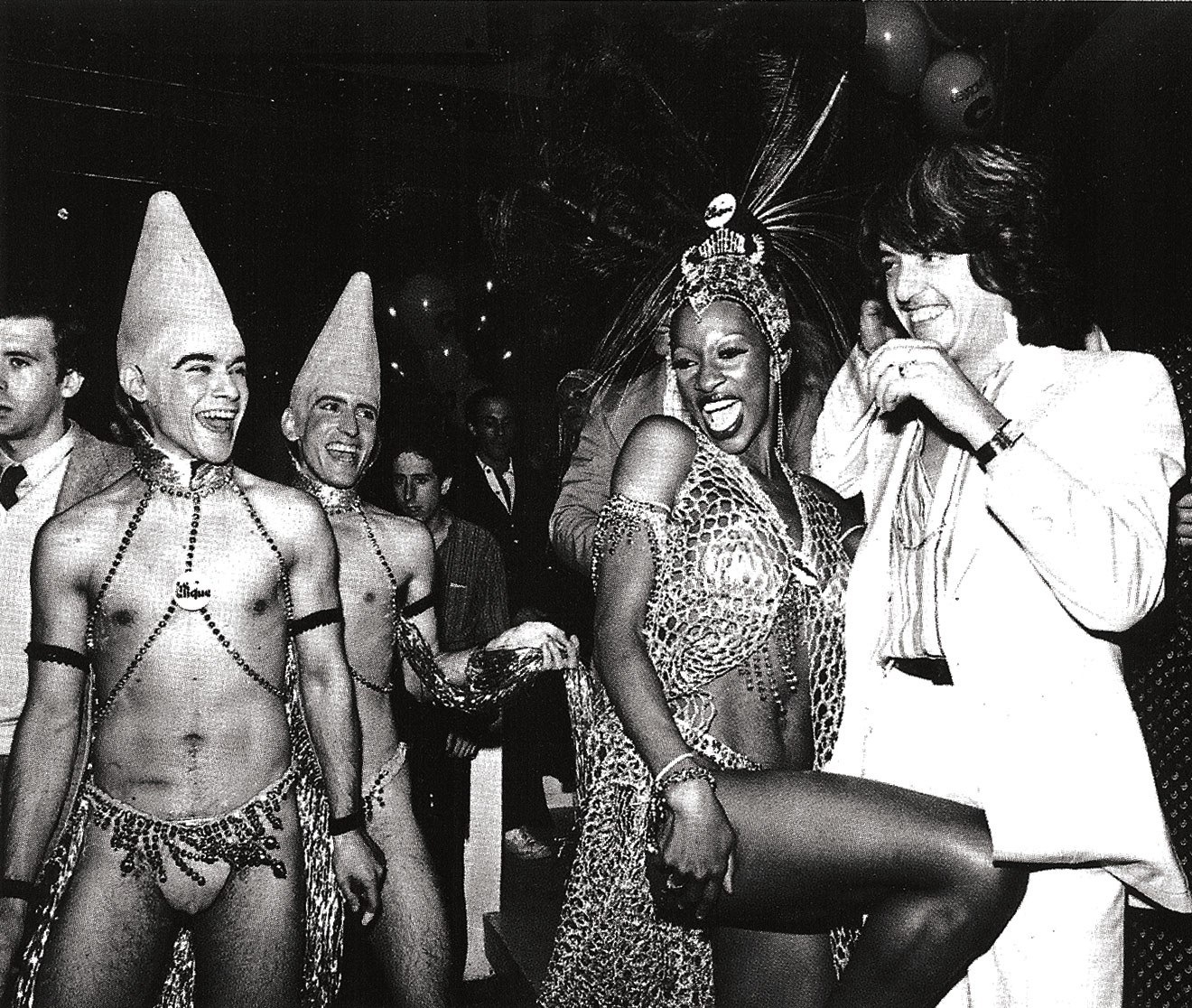

Cerrone’s success coincided with the peak years of excess at Studio 54. “I played there many times!” he says. “I had so many incredible nights in the VIP area, hanging out with Jean-Paul Gaultier, Andy Warhol and Jean-Paul Goude. We were all provocateurs, basically.” He pauses. I can’t tell you what happened.” Why? “Because there was a lot of sex, a lot of drugs and a lot of fun. Moreover, it was private.” He lets out a chuckle. What happens in Studio, stays in Studio.

One of French disco’s unsung heroines is the singer/songwriter Lene Lovich. She’s mainly remembered in the UK for 6Music staple ‘Lucky Number’, a big hit in 1979, but a chance encounter with Cerrone took her on a new path. “I met her in the street in London,” laughs Cerrone. “One afternoon in Piccadilly Circus I was in a cafe having a drink with a friend from Trident Studios and we saw the Hare Krishnas on the street and Lene was [with them]. She was so strange. We were looking at her and thinking, ‘What is she?’ She had red hair, a straw bird on her head, no shoes and she was singing in the street. I thought: what a fucking girl. She came up to me and said, ‘Why are you looking at me like that?!’” Cerrone invited her to Trident Studio to listen to his songs. Within two days, she had returned with the lyrics for ‘Paradise’. She subsequently worked on several of his albums, including providing the ecological theme for ‘Supernature’, perhaps his greatest ever song, inspired by HG Wells’ dystopian story The Island of Dr Moreau.

Read this next: Giorgio Moroder's Top 5 Soundtracks

These days, Cerrone is both a DJ and a performer. After resisting the lure of the DJ booth, he was persuaded by his record label to give it a go. “My first reaction was ‘I’m a musician – I don’t want to do this’. But I tried, and it was wonderful. Now five years have passed and I’m lucky that I do lots of big festivals.” In fact, his new album, ‘DNA’, developed from his DJ sets, as he produced more and more music to use between his own productions. “So what becoming a DJ did was take me back to when I first produced songs like ‘Love In C Minor’ and ‘Supernature’, which was my early electronic music. It gave me the opportunity to return to those roots.

“I’m lucky enough to still be on stage after so many years and it’s thanks to DJs, because they’re the ones who kept the door open for me,” he explains. “I’ve had so many remixes or samples of my music.”

It’s hardly surprising that a guy born with rhythm in his hands and feet is still internationally fêted, thanks to a run of releases and productions that are only now being fully appreciated. Nile Rodgers sums it up: “His contribution to dance music may be as important as Giorgio Moroder and Kraftwerk.”

The Lindstrøm & Prins Thomas mix of Cerrone’s ‘The Impact’ is out now; ‘DNA’ follows early 2020

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs