Features

Features

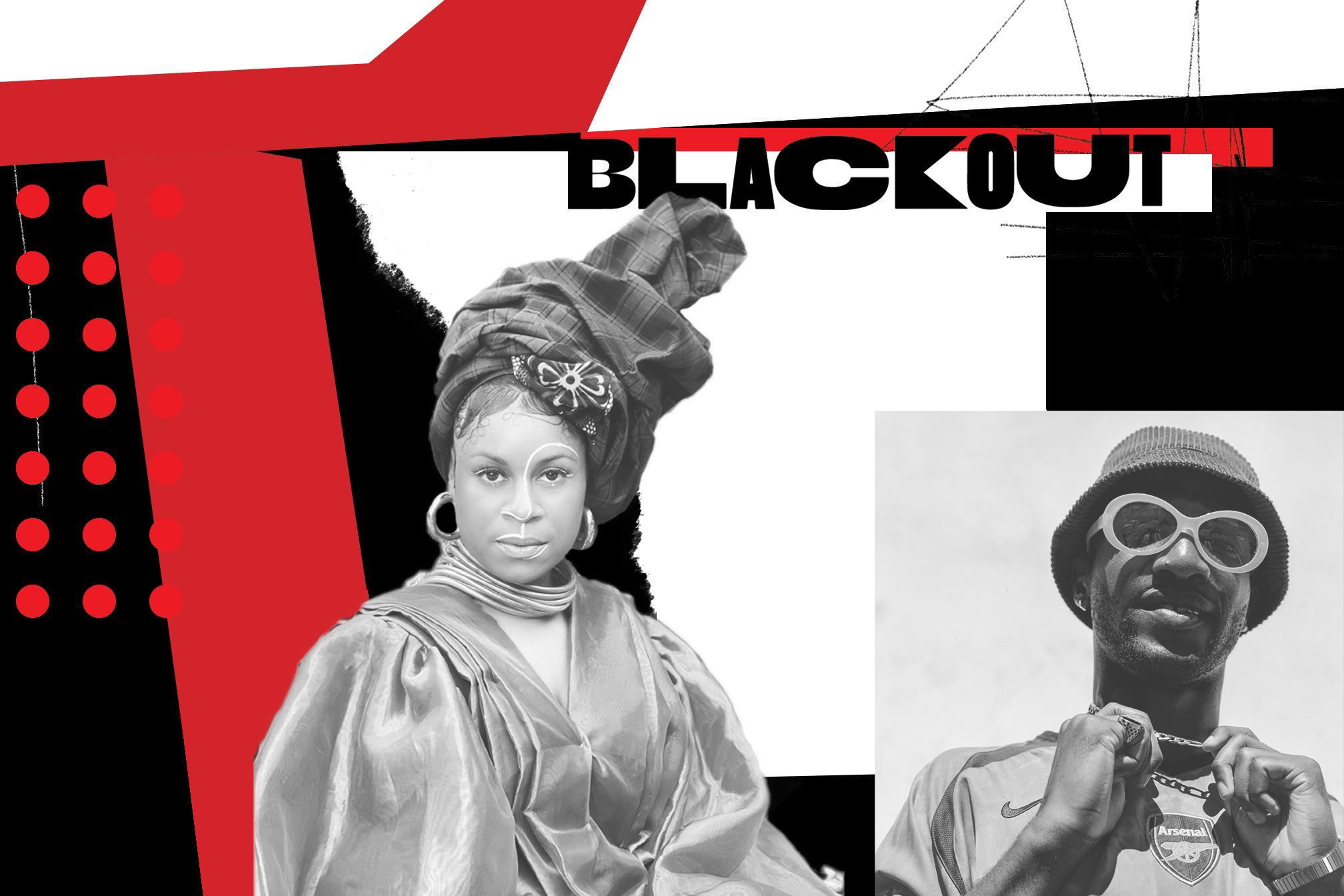

Aluna: "I get asked daily to be exploited by a white DJ"

Aluna and Conducta discuss being Black in dance music, how to build a better future, and why you should sometimes bite the hand that feeds

Aluna and Conducta are a proven to potent musical pairing, with the latter's Kiwi Rekords cohort recently remixing cuts from Aluna's debut solo album and producing ‘Renaissance (Kiwi Remixes)’ EP — a perfect tonic to SAD season that's brimming with mood-elevating energy.

Independently they're also both crucial voices in the dance music community, working to uplift Black people and call out white supremacist behaviours. Aluna recently penned an open letter challenging the scene to tackle "long standing racial inequalities", and Conducta has been steadfast in his support for fellow Black artists and commitment to re-educating people on dance music's historical Blackness.

As we continue our Blackout series beyond the recent Blackout Week, we bring to you a conversation between Aluna and Conducta about the exploitation of Black artists in the music industry, the whitewashing of dance music's roots, their plans for creating and sustaining spaces for Black people in music, and more.

Read their conversation below.

Aluna: I’m curious about the way that, historically, the government has come up with different pieces of legislation that have affected Black dance music culture. Do you know about Form 696 and have you experienced that personally? Because I didn't live in London, I grew up in St Albans where we didn't have a single club, so the loss of the club scene wasn't something that I was aware of.

Conducta: I grew up in Bristol, and then I moved to London when I was 18. Bristol club-wise was popping and nightlife had always been a thing. In London it seemed like there was a direct plan of action to get rid of clubs. I remember when I first came to London, there was Cable, Rhythm Factory — there were so many clubs in East London which are all now either pubs or accommodation.

It's interesting that at the beginning, you wouldn't see certain genres on flyers. It would be rare to see grime, garage or hip hop on a flyer, because that would be a trigger point [for the police] to ban them with Form 696. I remember many times having to do shows and the promoter would ask me for my name, address, and all these kind of things. It was only about two or so years ago that I clocked this was all because of Form 696. I kind of thought the way Black music in general was treated, in terms of not being on flyers and stuff, that there was a general consensus that mainstream clubs didn't want to fuck with that kind of stuff and it was put to the side. But knowing it was a concentrated effort to eradicate shows happening was a revelation, although not really surprising.

Aluna: In a sense, without the in depth knowledge, you get this kind of vague acceptance that: ‘oh yeah, nobody wants Black people dancing, definitely not’. You're thinking, that's a kind of feeling and opinion. But it's a targeted piece of legislation where that opinion is backed up by a system that can actually eradicate that. It's not like some guys being like, well, the club will get a bit riled so I'd prefer not, it's not about that. I think it's important to know how that affects an entire genre and culture of people.

Conducta: 100%. That in particular contributes to something you spoke about in your open letter, in terms of the whitewashing of dance music in general. I kind of mentioned it in my DJ Mag cover, about how it's funny that if you show an average white teenager who listens to music a drill tune and a Kerri Chandler tune, they'll think that a white person made the Kerri Chandler tune, because house and techno's been whitewashed by people thinking it's these white DJs making house music, when the origins of that come from Black people. That's been completely eradicated to the point where there needs to be a real re-education in terms of dance music.

Aluna: Have you sat down and learned or do you just happen to know the history of garage and how the sound developed?

Conducta: My first real experience of garage was So Solid Crew, and seeing them on and '21 Seconds' on MTV Base was like: wow, this is garage music. And then it kind of came from my godbrother with tape packs from Sidewinder shows, Dizzee Rascal, Heartless Crew, Wiley and all those kind of things. That was all around when I was 13/14. I only really got into the history of where garage and house came from and all that around four or five years ago. It's taken me however long.. I'm 26 now, I wasn't really aware of that history and the culture and heritage of dance music until I was 21 or 22. Again, that's in the context of me being conditioned to be like, if I see another Black person in the club I should feel like: oh wow, we both got in!

Aluna: [laughs] Oh my god!

Conducta: That's what's mad; I would be genuinely surprised when I played shows if I saw more than five or six other Black people in there. And even when you're in the show, you're going to get asked if you have drugs on you. Throughout my whole clubbing experience and being a DJ, the amount of nights someone would ask me like 'yo, you got anything?'. Even at a point maybe two or so years ago, I was backstage getting ready to go and DJ and someone asked me for pills, not even acknowledging the fact I might be performing, just assuming that I was someone's tag-a-long or a dealer.

Read this next: Marshall Jefferson: Why I quit DJing

Aluna: It's also interesting the way that affects the genre identification and classification. House and garage are seen as separate to grime, aren't they? Grime is definitely 'urban Black music', right? And then house and garage got separated from it. I feel like the link of house and garage to dance music is also separate; it didn't get carried on in the mainstream with 'dance music'.

Conducta: I've been trying to articulate exactly what you've just said, but not been able to articulate it like that. I think that's exactly what happened in terms of, the lineage of tracing jungle to acid house to house to garage to what grime became is there, but in the mainstream, grime got put into this thing over here, and house and garage got put in this [other] thing over here. And then even within house and garage, when EDM became a thing all of the foundations and roots of where EDM came from, which was house music, again got marginalised and pushed down to the bottom, and put into this new specialist box.

Aluna: So, when someone's asking me for example, 'why is mainstream dance music so white?' — it's like there was filtering process throughout history. You've got all these different types of dance music, and anything that was Black culturally, in a visible way, was taken out as a, like, subgenre. And then anything that was able to was turned into a white culture, like the house part of house and garage, that had a pop moment really in the 90s. That's where I started to notice the normalisation of using Black women's voices without celebrating Black women at all; that's how I grew up seeing Black singers. I think a big moment for me was seeing Moby and all of the depth to his music was from these Black voices, and he was this bald white guy. I was like, I don't understand. I certainly think he was influenced by Black music through and through, but he was so revered. Like, 'wow! Moby, what a genius'.

Conducta: I think again it kind goes to, there's people, often white people, in power who will fail to acknowledge the roots of dance music, or they’ll pretend to acknowledge but they definitely won't amplify the roots and Black people within music. Exactly what you're saying about female vocalists: I hate to hear demos now when I hear someone sample Brandy or Ashanti or these r'n'b singers, because... put it this way: I've seen producers who have sampled many Black artists but chill with golliwogs in Facebook profile photos and think that's fine.

Aluna: Is that still going on? Americans don't know what a golliwog is. If you go on a tour round Europe, in the Netherlands or something, you find whole shops dedicated to golliwogs. They're like, strung up in the window! What the fuck.

How about this: if you were going to throw a percentage out there of dance heads - not Black dance heads, but general, mainstream DJ dance heads - how many of them believe that dance music was invented in Europe?

Conducta: I reckon probably like 90%.

Aluna: Isn't that crazy? And if you tell them it was invented in Chicago and Detroit in the the late 70s and 1980s, they will in your face deny it.

Conducta: They will hard deny it.

Aluna: Hard explain that we're crazy and stupid, and ‘can't we hear the difference’.

Read this next: Kevin Saunderson: “Black people don’t even know that techno came from Black artists”

Conducta: Of that 90% though, I'd say that now there is no real excuse. All of those DJs have more than enough access to information and the cognitive ability to understand things. More often than not they choose to actively deny things or don't want to accept things because they don't want it to affect them. It's funny, loads of them won't say stuff because they know that their fans will react a particular way. Even if they believe what they want to say, they won't speak out on particular things because they know the backlash it will get. They don't have the bravery or moral compass to stand on the right side of things.

Aluna: You know what I think? Even if they admitted it, almost like 100% of those people would say: 'yeah but we made it better'.

Conducta: Yep, that's the other side.

Aluna: 'We took your primitive, basic idea and we developed it into this mainstream sound that you hear today' — I can see how pride and a delusional perspective would lead you to that conclusion. But it is to say that, if Black people were able to sustain that industry within our community, we would have developed it.

Conducta: 100%.

Aluna: The other thing to say is, if you look at all the subgenres, we have developed it. We've been making that music. If you look around the globe, you've got dancehall, Afrobeats, you know, Black people have been making dance music since the European sound went mainstream. For me, there's two things that need to be done. One is obviously the history of where mainstream dance music comes from. But it's also un-reversing that filtering process. Let's be real here, grime is dance, house and garage is dance, drum 'n' bass is dance, Afrobeats is dance, dancehall is dance, it's not reggae. I feel that that's such a bigger fight. You can get someone at Spotify or Apple who's running things to admit that dance music was created by Black people, but it's a much harder task to be like: now embrace all of those different genres into the umbrella of your mainstream money-making machine please.

Conducta: I feel like the reason it's evident that battle is hard is because I think there's almost a correlation between DJs who were quiet and didn't really say anything during that whole week where everyone wanted to apologise for being racist and the black squares and stuff, and the DJs who are now fighting for shows and saying 'we need to be able to DJ, this COVID stuff isn't right'. Because their money is being affected they're willing to speak out on stuff. When it comes to making line-ups more equal, or promoters being like 'cool let's actually have some Black women on here, let's have some Black DJs on here', of course none of them are gonna be like 'let me even the playing field'. Unfortunately I think that’s because inherently within a lot of DJs and people within dance music, if it was a chance to make the scene or community 10% better or make themselves 2% better, they'd always go for the 2%. A lot of people just want to pillage whatever community or scene they're in, get to the top of it, and continue to pillage it until it's dry and not really give back.

Aluna: Yeah. This is the thing, if white producers wanted to continue to stay in their own bubble, make their own music, and not fuck with Black people at all — I'm talking, if you are not allowed to sample a Black person, you've got to take all the Blackness out of your music, you can't touch it — I'd be like, ok, keep your genre how you want it. You stole it, keep it. But I get asked daily to be exploited by a white DJ. They want to exploit Blackness so deeply; it's so deeply rooted, so inherent. At first when you're coming up, especially as a young Black woman, you're seen as opportunity. So when they ask to exploit you, it's like a business exchange. It's: give me your soul and your uniqueness and your flavour, and I will give you... well, normally the way it goes is 'exposure' right? I'm like, yeah, 'exposure', hmmm. Can I eat 'exposure'?

There's different types of exposure. I think they need to keep the 'exp', then the rest of it make 'exploitation'. It doesn't add up... Sometimes it does: being exploited has basically created the career that I have. But these things go through my head. First of all, the hypocrisy of me talking about the Blaxploitation that happens at the same time as accepting those offers in order to feed my kid, right? There's that kind of hypocrisy that you deal with in your own mind. At the same time as saying 'this is unfair', you're taking the deal. But on the other hand, I feel like that particular type of feeling like a hypocrite, taking the deal, silences us. The fear of being told 'if you don't like it, don't fucking take the deal'.

Read this next: The exploitation of Black women vocalists in house music

Conducta: In terms of my experience of being used and exploited, I feel as unfortunately again it kind of goes back to: it's a shame and it's sad and it shouldn't happen that anyone's first experience of dealing with a label or anything on a big scale is always a bad one, always a burn. I often think that the way major label systems work and they exploit rappers now, young kids essentially, is like modern day slavery. Not to go on the Kanye kind of thing, but in terms of, you're actively tricking and looking for kids to trick to play a lottery of 'yeah this might work, this might make us money, but we don't care [about the artist]'. And they'll happily carry on doing that and pillaging, playing off violence and gang culture and things where it's ok in that corner as long as it doesn't affect their day-to-day life. Like, 'go and be Black over there, go and do your thing, then we make money off of it'. It's distressing to see. And when you have life obligations, if you have stuff to do and want to get out [of contracts], it's like money rules the world so what can you do? You sometimes have to take the hit to therefore even live to tell the tale.

Aluna: This is what I would like to do: next massive DJ that offers me whatever deal it is to use my voice, I will be like: ‘yes you can exploit me in exchange for that money’. Here's what I get: 'I'm a massive fan, I really think you'd kill this record I've got, you've got a really unique voice' or whatever it is. Delete, delete, delete. This is what I would love: 'Hi Aluna, I'd really love to exploit your Blackness to make my music sound like it's got soul, to make me seem deep, and also to freshen my sound, because I don't know how to speak to people, I've got nothing to say, I can't sing and I can't dance. Without you, or someone like you, I can't connect with anyone, so can I please exploit you?’.

Conducta: [laughs]

Aluna: Somebody please email me that! I would be like, 'yes you can! Right now, put the money down, give me the bag let's do this'. But it's this pretence. I have to be like, 'oh my god, you're going to give me exposure? Thank you!'.

Conducta: It's almost like... I don't want to say white saviour complex—

Aluna: How many times do you get called a 'legend'? Like, what are you talking about? More like loser; call me a loser. Correct your language, what do you really mean? 'Listen loser, you can't be a solo act without me, you have to be a featured artist for your entire career, because people don't invest in Black women'.

Aluna: You're a Black man, right, so you're more in the lane of - correct me if I'm wrong - 'oh you're going to go it alone aren't you?'. When someone is doing a festival line-up and they're looking at you, and they're looking at 100,000 other white DJs, are you going to get booked?

Conducta: There's certain festivals that in my head I know I'll never play.

Aluna: What the fuck does that feel like?

Conducta: I don't know if this is a good or bad thing, but I feel like now I've conditioned myself to not really care, because it's not for me. I know that exists, I know that's over there and how they move — it's gone past the stage of having to bend over backwards to do stuff. I feel as if, being Black anyway, you have to be extra-extraordinary, or do something incredible in comparison to any white mediocrity around you that's not even close to half as good. My battle has been to essentially just create my own space and make my own ways to not rely on people who don't really give a fuck.

Aluna: So you're working outside of the system?

Conducta: Trying to! It's annoying because you have to dip in and out of that system to sustain and build outside of it. But there's spaces for us, and it's about finding and also creating those spaces. That's the way I kind of see stuff. For example, I don't think I'll ever do a Radio 1 Essential Mix.

Aluna: I know you've even said it yourself: it's a strategy to keep moving forwards, right? Finding and creating your own culture so that you don't have to even fight with the white side of dance culture, the mainstream culture. I have always noticed that I could make my life, on the one hand, easier if I did 'Black stuff', if I stayed out of those lanes. But I didn't, so what I find is that I am at HARD Summer fest on a white DJs' stage in front of their massive white audience. But guess what? There's two Black people in there. Then I'm like, 'fuck, what are you doing here? You're not safe!'. So now I'm like, well I can't just leave you here. So that's why I did this solo project. Once you see that there are some Black people trying to reclaim spaces for themselves where they're not wanted, I feel obliged to be like, I will create a space for you here. I've had to do things like go, well, that's for white people, but it was originally Black and it's time to reclaim it.

I just wonder — from your position where you have a certain comfort in knowing that you can stay in the cultural world that you've found and developed and are the centre of almost — can you see yourself going: but also, that's mine, I'm coming for it, I'm coming for my space, I'm coming for my Essential Mix, I'm coming for my stage at HARD Summer festival, do you ever think about that? I know that you're focusing on your work, what you're doing now, but do you daydream about those kinds of things?

Conducta: Sometimes yes, because I know what doors it can open. I know that when you're a token or have been used for something and exploited that way, you always have that kind of shitty feeling of 'fuck's sake'. But for me it's like, I know what good I can do. Anytime I see a Black producer making garage or dance music, I immediately try to empower them and help them because I know we've probably gone through similar things. But there's been occasions where you'll deal with someone who's been conditioned in a particular way to chase this or that.

I feel as if now, it's a privilege, I don't necessarily have to chase particular things. Whereas a couple of years ago, I was 100% chasing those things, because I felt like that's what I needed to do, I needed to jump through all these hoops. But the issue with that is you'll keep on jumping through these hoops and you'll keep on needing to do stuff to satisfy people. You'll be like that guy, you know that BBC dancer who does the body locking and the breakdancing? You don't want to be that person where you're just trying to entertain white people. I feel comfortable now not having or wanting that, or putting that on a pedestal. Because that's the issue as well, these things are kind of put on a pedestal to us. When you're Black you have to work 10 times harder for everything. Nothing is ever really given to you, especially within dance music. You have to grind for it, and you know that the six other people, your peers, who are white probably haven't put in or had to be as resilient or go through any of the stuff you've been through.

Read this next: How the Dance Music Industry failed Black Artists

Aluna: So, really the solution is for Black people to continue to invest in our own culture, even as subgenred and unsupported as it is?

Conducta: I think that's the best way.

Aluna: Because white people ask what we want from them, right? So, is it: nothing thanks, we'll do our own thing? You've got to remember, again, what the ceiling of that is. With stuff like Form 696, how can we build our own culture, with us in it, without mixing with the white allies?

Conducta: I think it's a case by case thing. Usually in a lot of these communal spaces, whenever it's anything to do with racism or homophobia, people try and put these things down as societal issues. If it's racism in football, or racism in music, or homophobia in football, it's like: ‘these are societal issues’. All these things are little microcosms of how the real world sees things, and at the top of a lot of things, people hold these views that don't align with ours. It is possible that there are allies and there are people that do care and want to make a difference, and being able to identify them and them helping to integrate the platforms we already have into the mainstream definitely does help. Personally, I feel as if I dip in and out, and I'm able to do things like be on the DJ Mag cover. It was nice to have my friends and other upcoming DJs and producers be like: 'oh wow, I never knew you went through all of this, it's amazing to see and it’s inspiring that if you can overcome it then it's something that I can do'. I feel people like me have that responsibility to be a constant reminder that, yeah, fuck all that stuff, we're still here and we're still doing our thing.

Aluna: So it's like: mentor each other, build each other up, and then when we get to a certain level we can make collaborative ventures with the white dance community?

Conducta: Yeah.

Aluna: From a position of foundation build up, it's a strong one.

Conducta: For sure. Because I feel as if you forget that they want you. You feel as if you're offering something to them, but really they want you because of how brilliant we are. For any kind of conversation or negotiation, they should be in a position of respecting, acknowledging and wanting to really positively support us in the right ways. Rather than, as you say, just shamelessly exploit.

Aluna: Well that seems to be the only deal that gets offered a lot of time, isn't it? It comes down to money as well. Here's the thing, if you're coming up, say there's two deals, one from the Black community and one from the white community, one of those you're gonna eat off and one of them you're not. That's what it comes to. The reason that the white dance community and industry is so successful is because they have been able to financially back that entire industry.

Conducta: Yeah. Again, it's difficult, because like you say, we have to eat and provide. When you're faced with the decision of those two options, more often than not the person is going to take the money option. Whenever I've been faced with something close to that, I always try just land on my morals and let my integrity kind of direct what the right thing to do is. Because I think now, as you experience more stuff within music and you get older and you're more well versed in the tricks and lingo people use, you have a very good radar as to what people's interests are, what they actually want from a transaction. Do they really care for what you're doing and what you stand for, or are they here just to amplify and make money for whichever white guy is employing them?

Read this next: Annie Mac: "There's not enough Black people in every level of the music industry"

Aluna: Ultimately, what you're talking about is ownership. Maybe that is the only way to really change the industry, for Black investors and the up and comings to collaborate more. If you are gonna do a deal with a white record label, someone on that team might be an ally, but ultimately there's no ownership at the head of that that looks like you. And so... I didn't even say the phrase earlier that I was going to: 'you don't bite the hand that feeds you'. Whereas, we're saying: bite it.

Conducta: Yeah, nibble [laughs]

Aluna: Bite that hand, and yeah, those opportunities will get taken away, but as a Black community we will be able to [have ownership], like we see in AFROPUNK. I'd love to be able to talk to people that created that festival in a very competitive world but have shown that investing in Black owned industry in the music industry works. And so have you. You’re an example of ownership within the industry, and how that gives back to the community. You feel like you can look at the racism that exists from a position of strength, in a way.

Conducta: Yeah. In terms of my story to get to where I am now—when I was in my record deal and it was going awful and I wasn't able to release music and was feeling suicidal, I think it would have been very easy thing to do to keep on riding down that path: get out of that deal, go to another deal, make some more music, kind of just be selfish and not really want to give back to any community. People do it. Even being dropped, I could have just done my own thing. But for me I always feel that obligation to not just create community, but to uplift others and show everyone ‘I've been in the building and this is what happened, you can make that mistake if you want', and 'here's how I responded to that mistake that I made'. Because the issue is, when you're Black, not only do you have to work insanely hard, but if you make a mistake, the recovery is very hard. You feel pressure because if you make mistakes you know that you're almost put into oblivion; I think that's the pressure there. I aim to show people that you can come out of that pressure, you can make that mistake and there is a way back. You have to be resilient and it's hard, but there is a way back from that kind of thing.

Aluna: I was talking to a group of Black people who had been responsible for creating the hip hop genre and consumer experience at DSPs, and how because there was no Black ownership and leadership at the very top, those people invested all of their selves into the growth of the culture at those platforms, but then the racism was such that they did have to leave in the end. But they had to leave behind what they built. That thing about ownership with what you've built, you'll never have to leave that behind, and I think that's a really important thing to realise as a Black person.

Your entrepreneurial skills are very much needed at these big music corporations and jobs are available, and it's exciting because you see, for example, someone who's doing really bad in one area of Black culture and you know all about it and can go in there, advise them and fix it and be a king of the castle for a week. But when the shit hits the fan, you're gonna want to leave, and you'll leave all your legacy.

I think not underestimating your power as a Black person within those fields has to be taught and mentored to young executives and entrepreneurs, and where to put their energy. It's no small thing to think that, by not investing your time and energy in a white industry that you're going to be giving yourself setbacks, but someone like you can explain the value at the other end of it. The value isn't really that pay cheque, as much as we want it. If you're not on the poverty line—let's be honest, there are plenty of Black people who are not on the poverty line who would still take the bag over and above their feeling of self worth in the progression of their career. I think that's the kind of spot where we can find traction and change in the future. Obviously we can't go round saying to people who are still living in poverty 'don't take the bag', but there is that kind of bubbling middle/lower middle class/aspiring to middle class community of Black people now that need to be spoken too.

Conducta: Another thing is that, a lot of the time, a big thing in music or in general is representation. As I said, I remember going to clubs or looking at DJs and just seeing a bunch of white guys. I didn't know any Black dance/electronic/garage/house DJs; it was just whitewashed.

It's been good to get Black people on the label [Kiwi Rekords] and release them and give them a platform. It's such a nice feeling, like: Prescribe Da Vibe, when we released his EP at the beginning of the year he got put on some big playlist by a producer and he text me like 'yo I can't believe how well the EP is going down'. That just made me smile. He's making music in his bedroom, probably didn't take it that seriously, probably would have stopped to be honest if there wasn't a lot going on or would have just done it in his spare time — but for him to have those small moments of joy and having people appreciate his music and it be on a platform, for me, those are the little wins that give me hope. I just want to keep on doing stuff like that and putting people on, shining a light on people who deserve it and wouldn't otherwise otherwise get it in a white dance music world.

As well as dismantling it being a white club, I wanna be able to dismantle it being a boys’ club. That for me is the next step, giving women more confidence. Because in terms of production and stuff, from what I’ve seen in dance music I almost feel as if you’re [seen as] ‘just singers’. It's a real shame and I feel like that's the generational issue or problem that I definitely want to contribute to tackling. Because I see it and I dislike it, it rubs me the wrong way. There's a couple of producers that I've spotted and I think have a lot of potential. For me, that's my next challenge really.

When I think back to when I was feeling suicidal and not wanting to do music anymore, I think that I do have this platform and this obligation, and I am able to help and put people on. I just want to do that as much as I can. I feel like between the previous generation of people who made garage, there was no bridging of that gap. When I came to London and was making music, there was no one who I could really be like, 'oh cool you're making garage as well?', especially a Black person. That's why I feel such an emphasis and responsibility to support if I see a Black producer.

Read this next: The unsung Black women pioneers of house music

Aluna: This has been really cool. I think we've both talked about the disparities in the industry, but also kind of pointed to some really strong mindset solutions. I ain't relying on anyone else changing, because sometimes it feels like you'll wait forever. It's almost like, yes, we can keep educating the white industry on how they can make changes, but half of the time that will fall on deaf ears, and while those ears are plugged up with cotton wool, we're doing our own thing, we're building.

I think one uplifting thing that I like and really cheers me up is thinking about how fun it is to build something from a genuine perspective. There's no stealing involved in what we do. There's something really juicy about a first, being first, or reviving something, reclaiming something. Although it comes from a negative of having things taken away from us, it is also so life-affirming and exciting to rebuild something and uplift people who've never been uplifted before, or surprise the world with what they've overlooked and underestimated. For me, that's just really exciting. I suppose my only real reason for pointing out all the bad stuff and the shitty stuff is in order to identify all the really exciting things to do! You've just shown and talked about so many of those exciting things that come out of adversity. It's really inspiring.

As a Black woman, I do feel like I'm a few steps behind man in my ability to uplift and bring up and mentor and all those kinds of things. As a mum I have a really strong desire for that, but I'm battling sexism and racism within the industry so I get to a point where I'm like, I can't do any more. But that desire never goes away, I'm like: I need to somehow uplift young Black women to be producers. I don't know how to do it, it's gonna be a long time. But at the same time it's really exciting to think about.

‘Renaissance (Kiwi Remixes)’ is out now, get it via Bandcamp

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs