Features

Features

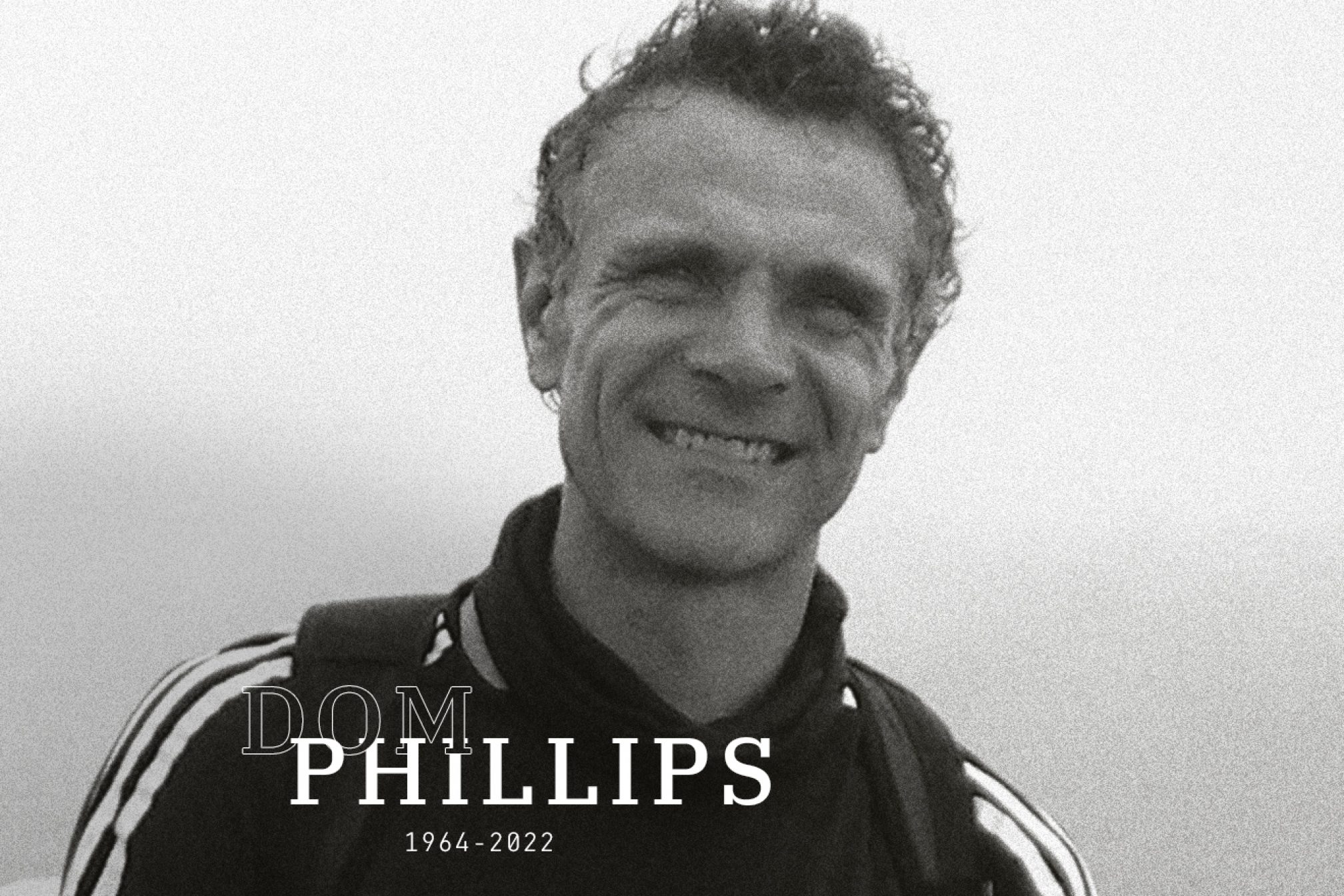

Unshakeable truth-seeker: Dom Phillips’ burning love for humanity fuelled his brave journalism

Frank Broughton pays tribute to his close friend and former Mixmag editor Dom Phillips, a curious and courageous journalist who was working to protect the world

“There are chickens on the dancefloor!”

It’s New York 1992 and I’m in a freezing Williamsburg warehouse with Dom Phillips. You can see your breath. The local artists are doing their best to create a happening. Which means a stack of day-glo-painted TVs tuned to static, a deal of bad graffiti, and clumps of weird knitted-together junk in every corner. Someone is swimming in a fish tank with a video camera looking at their knees. The floor is genuinely filthy. There’s music but it’s hardly a rave yet… though who knows! Apparently, upstairs on the roof they’re firing up a barbecue. Dom fears for the chickens.

I’m living in Brooklyn – round the corner – and Dom is an editor I write for who’s visiting from London. We’re in our twenties and life is full of strange possibilities.

“Look at the ceiling, all those Christmas trees.”

“Upside down!”

I think it might be his first time in New York, I’m not sure. But it’s the first time we’ve met and I’m doing my best to show off my adopted city. Dom’s the perfect guest for this – endlessly curious, question after question, excited to meet people, always charming. The next day we walk over the bridge to eat Puerto Rican food on Delancey and marvel at the shop windows full of hip hop jewellery and late-model boomboxes.

Dom made me a writer. I’d been doing reviews and little music pieces for various mags, then in 1991 he gave me my first feature: “Techno takes New York”. He generously guided me, helped me structure it, even sourced some supporting quotes. Dom was Assistant Editor, then Editor, at Mixmag through the clubbing explosion of the nineties, and similarly mentored a generation of writers, photographers and nightworld ne’er-do-wells, as he brought pro journalist standards to the woolly world of dance mags. Among the snare rolls and the fluffy bras, Dom saw the bigger picture, and his writing brilliantly documented both the evolution of the music (it was Dom who coined the genre tag “progressive house” for example), and the emerging culture of nightclubbing-as-lifestyle. Under Dom, Mixmag questioned the spiralling wages DJs were earning and captured the emergence of the superstar DJ. His famous cover "Sasha: Son of God?" led to Dom and a miffed Sasha tussling physically outside Ministry of Sound.

In Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, the book Bill Brewster and I wrote in 1999, Dom’s voice rings out throughout, offering unmatched insight. He gave us great insider stories about the industry, but also eloquent words about the passion of the dancefloor. That was Dom, always speaking from the head and the heart.

On the Saturday, with my girlfriend June, we go see Frankie Knuckles at The Roxy, a vast swirling floor of fabulousness driven by house pianos and glitter vocals, in the company of Joseph and Reggie and the other giggly Filipinas; followed at 4:AM by the weekly pilgrimage nine blocks north to the Sound Factory, an altogether more serious dancefloor. Here Junior Vasquez wrings us out and squeezes us into Sunday afternoon. The energy of the place is always incredible: an endless ferocious tribal stomp, otherworldly deep house, Wild Pitch epics. No bystanders, no chit-chat, no booze, amazing sound, incredible lights – this is communion. Dom is blown away and throws himself into the action. In Mixmag he declares it, “the ultimate in clubbing”. But he’s also fascinated by the social make-up of the place and needs to know the stories of the different dancefloor families: the banjee boys working their little runway, the bulky gym queens swaying together on K, the DJs and dance label folk song-spotting under the booth.

Another day I take him to the East River off Kent Avenue, where a huge wasteland gives you the best views of Manhattan. At the river’s edge we see a man throwing a wholesale box of apples, one by one, into the river. I offer to take one off his hands, but he gestures that he can’t spare any and carries on throwing them in, watching them bob away in the current. His explanation is in Spanish, so Dom and I leave confused. I quite like the mystery but Dom is determined to solve it, and asks everyone what they think this guy was up to. He won’t leave the question unanswered. By the end of the day he’s got it: it was a Santeria thing, someone tells him. The apples were an offering to Ochun, the river goddess.

Many years later, I’m watching a video of Dom asking more questions. He’s in a dark suit with a crisp white shirt and he’s speaking Portuguese. He learned the language within a couple of years of moving to Brazil; within five or six he was writing articles about global economics in it. Now here he is, speaking directly to the new President about the rainforest. This is hard-right ex-military evangelist Jair Bolsonaro, the man who chilled ecologists by declaring the Amazon “open for business”. Dom points out that since his election, fines for eco violations have plummeted, and that the environment minister has been chumming around with gold miners: “The message the government is sending is not very positive,” he challenges, microphone in hand. “The new numbers on deforestation are showing a frightening increase. Sir, how do you intend to show the world that the government has a serious concern for the preservation of the Amazon?” The President looks irked, angry. “You need to understand,” he answers loftily, “the Amazon belongs to Brazil, not to you lot.” To Bolsonaro and many of his followers, the rainforest is a hindrance to Brazil’s development, an overgrown backyard filled with priceless minerals and expensive timber. On satellite images we watch it burn.

This was the moment I knew Dom was unshakable. These days speaking truth to power is rare. Truth is elusive and heavy to hold. And power has learnt to hide from anyone who might have truth to share. In the wrong place, truth carries penalties. So this is quite a moment. We watch Dom face to face with this dark force of geopolitics. Bolsonaro: the embodiment of twenty-first century human error. Like Trump, like Johnson, he has split his country down the middle with a great lie and ridden in on the chaos.

We watch, awed and a little scared. This is real bravery. That’s Dom up there on the world stage, asking difficult questions. Our Dom, with his 100-watt smile and his dimpled creases and his banjo and his gravelly laugh. While we piss around writing content for brands, here’s our mate at the sharp end of humanity’s future.

Dom was a real journalist, and he didn’t flinch. This was already his fourth act. Raised in Merseyside, in Bristol in 1988 he started a pirate station and an arts magazine – New City Press, then he helmed Mixmag, then he wrote a book getting under the skin of big-money DJ culture: Superstar DJs Here We Go. He went to Brazil to write it and never looked back. Instead, smitten by the country’s resilience and optimism, he got deeper and deeper into the place and its amazing stew of humans.

His next book was to be How to Save the Amazon. His aim was to make it as mainstream as possible, to give a loud voice to the indigenous locals and to suggest practical ways they might be empowered to develop and protect their homelands sustainably – the lungs of the one planet we have.

Except… Except Dom is no longer here to write it. For 10 days he was missing, then lost, now confirmed dead. He’s dead because there are a lot of people working towards a different ending for the Amazon. It’s a dark, twisted ending where the rainforest is ground down into money. The narcos rinse their coke there, tipping solvents into the groundwater so that richer people in safer places can have their drugs. The loggers cut roads deep into the jungle to pull out centuries-old trees for our fancy kitchen floors. The fishermen catch protected species to feed the narcos and the loggers. Behind them are the miners, and soon after, the oilmen and the cattle. Dom’s friend and guide Bruno Pereira, the man murdered with him, had been a brother to the rainforest and to the people who call it home. He once worked for the government to protect these people and their interests. But because he was good at his job, under Bolsonaro he lost it. And then because he carried on giving his life to the place, he lost that too.

The cruellest twist is Bolsonaro’s hateful dog whistle of encouragement to future murderers. In that area “anything could happen… they could have been executed”, he told the press in tacit, barely coded approval.

This was the last trip Dom needed to make for his book. Brave Dom who deserved to settle down with his beloved Alessandra, to have a quiet life in Salvador in the flat they’d just bought. To raise the kids they planned to adopt, to see his ideas gain strength and make a difference. If a guy like Dom can’t save us, someone with a pure heart, brave optimism, and a burning love for humanity, who will? Who will step up and finish the book for him?

A fundraiser has been set up to aid the families of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira. Donate here

Frank Broughton is an author and journalist