Features

Features

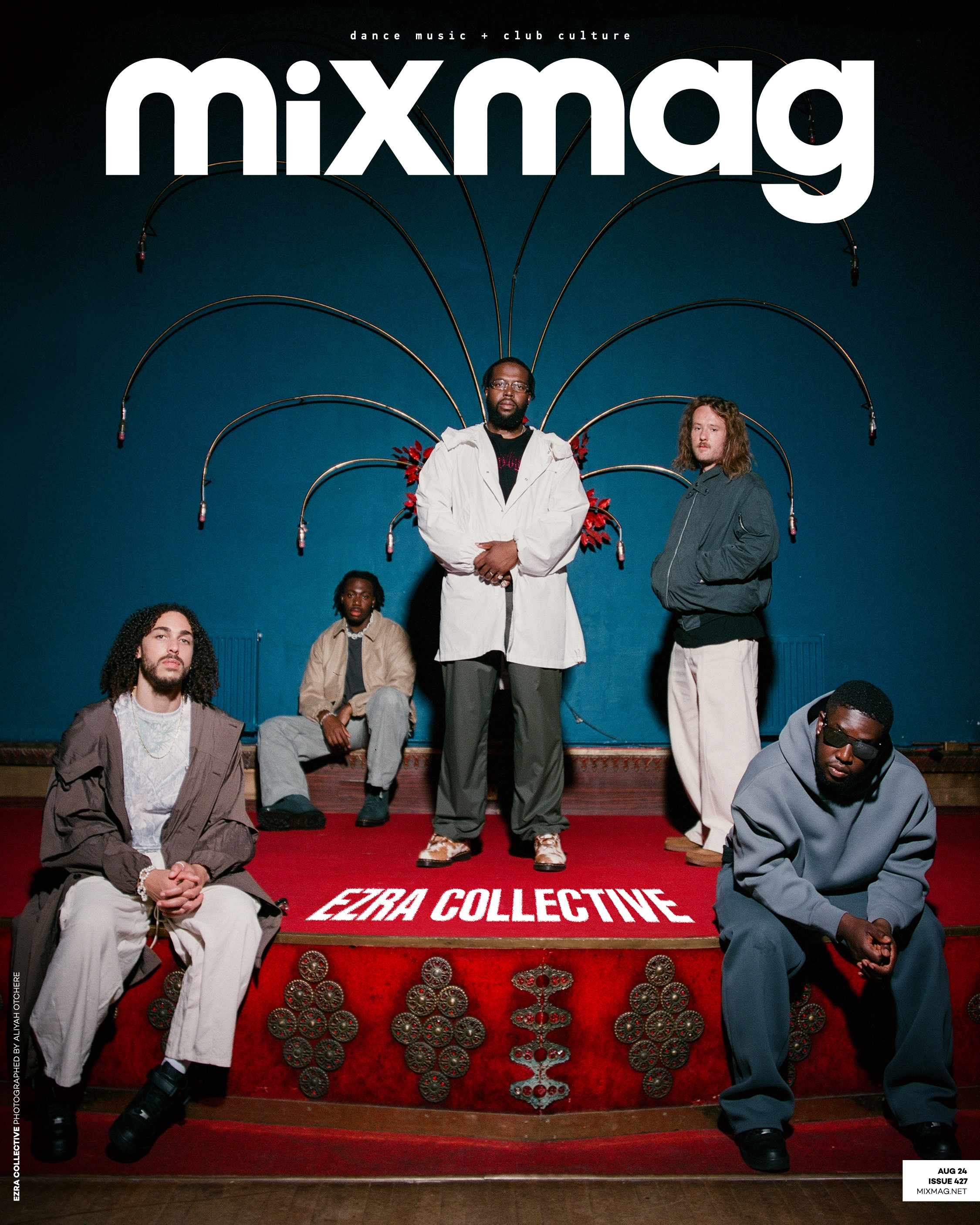

Free your body: Ezra Collective are bringing dancing back to jazz

Ahead of the release of their third album ‘Dance, No One’s Watching’, Ezra Collective speak to Sope Soetan translating the chaos of their live shows to record, the influence of church and travels, and rejecting elitism to help make jazz dance music again

If you ask Femi Koleoso, Ezra Collective’s drummer and bandleader, the dancefloor is in a state of emergency. A code red if you will. “Dancefloors, especially in London, have become too beautiful. Girls are in heels; boys are in chains. Everyone's wigs are pristine. Everyone's got a trim. Everyone's just super fit. Aren't we here to skank?” he questions. “I want to leave this place looking like I've been in a fight.”

I meet Koleoso alongside the band’s trumpeter Ife Ogunjobi on a warm Monday afternoon at Church Studios in Crouch End, North London. The historic recording facility has borne witness to altars and pulpits at the hands of myth-like giants such as George Clinton, Beyoncé, Patti Smith, Eurythmics, Jimmy Cliff, Kanye West and Sinead O’Connor. “VirgIl Abloh did a Louis Vuitton show for Tokyo Fashion Week. I was on drums for that and it was recorded here. That was the first time I came here”, Koleso recalls.

It is also where the quintet additionally comprising Joe-Armon Jones (piano/keyboards), James Mollison (tenor saxophone) and TJ Koleoso (bass), recorded the strings for their forthcoming third studio album, ‘Dance, No One’s Watching’.

Set for release on September 27, ‘Dance, No One’s Watching’ is a celebration of unadulterated freedom and cathartic impulse. More than just a record, it’s an imagined end goal, the ideal state of mind. It's informed by a mantra that developed while the band was on the road touring ‘Where I’m Meant To Be’, their 2022 Mercury Prize-winning breakthrough album which came to life during lockdown. “Albums are diary entries. A documentation of where you are right now. With ‘Where I’m Meant To Be’, it was our documentation of lockdown. With this record, it’s very much the documentation of ‘we’re back outside’,” Femi declares.

Read this next: The Cover Mix: Ezra Collective (Dance With EZ)

When listening to the 19-song collection, that sentiment is loud and clear. Through the four acts it’s split into - with titles ‘Cloakroom Link Up’, ‘In The Dance’, ‘Our Element’ and ‘Lights On’ - the album effortlessly simulates the communal feelings, moods and happenstances that occur on a night out from beginning to end. Ezra Collective star in the affair as the house band of an event that’s equal parts rave, blues party and Sunday morning service. “We wanted to take the listener on the journey we experienced watching people in places freeing themselves and their bodies. All the way from getting ready at home, to the cloakroom, to the dancefloor and even to the night bus”, Mollison shares, speaking over email.

Surprisingly, the album is at its most jubilant and merry on the ‘The Herald’ and ‘Everybody, their dual ode to the sound and atmosphere of the West African church.“The dancefloor I’m most frequently on is the church dancefloor. I wanted to diversify what people saw as the dancefloor. When done properly, the church can be so similar to the club”, Femi explains.

As the record’s opening and closing numbers, they serve to bookend the album in a very intentional manner. “‘The Herald’ means ‘the bringer of joy’ and ‘Everybody’ is about articulating the feeling of inclusivity,” notes Femi, referencing hallmarks that have long formed an integral part of Ezra Collective’s brand since their 2012 formation.

Like Olabisi Ajala, the Nigerian travel writer and journalist whose infamous trek across 87 countries on a Vespa scooter is immortalised on the album’s rhythmically grandiose lead single ‘Ajala’, Ezra used all they saw, touched, tasted and experienced on dancefloors across nations like Nigeria, Australia, Ireland, Turkey, Spain, New York and more to form the record’s stimulus.

Their time in Nigeria came via a humbling opportunity to perform at Femi Kuti’s fabled New Afrika Shrine, the open-air nightclub in Ikeja, Lagos State. It's created in the image of the original Afrika Shrine venue founded by his father Fela Kuti, which burned down in the 1970s. “Playing in a Black country for the first time was very, very, very deep for Ezra Collective, I saw so much of the culture I’ve known, lived, and grown up with in its most authentic version,” Femi emphatically states with a still noticeable essence of pure wonder and gratitude. It also signalled a posthumous co-sign from a landmark figure central to Ezra’s musical ecosystem. “That building’s significance to our musical identity goes without saying”, Mollison comments. Ife, however, was most moved by his encounters with the crowds in Japan. “It’s always interesting to see how everyone’s choice of dance can vary culturally. The way those guys jumped from minute one all the way to the end was crazy. Especially because you’d tend to think they’re more reserved,” he says.

Read this next: Tony Allen: The self-taught drummer who became the best in the world

It was during this trek that the album’s title was born. “On-stage early last year, I remember saying to an audience, ‘The only dance I want to see is a dance like no one's watching. I'm going to give every single person here permission to dance not mosh, not jump, but dance’,” recalls Femi. When I push on why he makes a point to specify the ban on moshing, Femi says: “They provide a hiding space that dancing doesn't. The problem is people feel a self-consciousness with dancing. The beauty of a mosh pit is everyone looks mad and no one cares. That's what a dancefloor should be like but it isn't. I wanted to make that distinction.”

This distinction is made abundantly clear by the album’s striking artwork. When I note that it reminded me of Marvin Gaye’s 1976 classic ‘I Want You’, Femi confirms that was deliberate. “It’s the most perfect depiction of what I believe the dancefloor should be. They’re not even looking at each other. They’re just in the moment,” he says. Indeed, when looking at that original iconic painting by Ernie Barnes, it’s hard not to notice the arched backs, the expressive faces, the complete loss of inhibition. It epitomises what dancefloors should be — a place to bring our collective guards down, a place where we can momentarily disarm our perceptive armours. A restorative place where everyone can be brought to the same level. “That picture became our mission statement,” declares Femi.

Ezra Collective have been called “the London jazz scene’s de facto party band”. Jazz purists will know that ensembles described as such are historically most associated with the swing era - the dance music of the 1930s and ’40s. Ezra Collective stylistically cannot and should not be grouped as being solely belonging to this tradition. The harmonic experimentation and complex musicianship shown on their delightful take of Wayne Shorter’s ‘Footprints’ alone disproves this. But perhaps unknowingly, purely by virtue of their motives and objectives as a band, they’ve taken on that role. This has been emphasised by the remix ‘JOY (Life Goes On)’, produced by electronic duo Joy Anonymous, becoming a staple in the club scene and infiltrating nightlife spaces with little to no relation to the jazz sphere.

When I ask if the album’s title could be interpreted as commentary on reclaiming jazz as a form of dance music, Femi drops a bomb. “I've not told anyone this, but one of the titles I was wrestling with was ‘Dance Music’. I was actually going to call it that because I think it's mad that's become a genre,” he says. Pushed for clarification, he adds. “By that, I mean an electronic form of music for people to dance to is now called dance music. If you say, ‘I'm into dance music’, that to me doesn't make sense as a sentence. So, you mean reggae? Hip hop? Dub? To me, it’s about what kind of dance music?”.

This is symptomatic of how jazz music, despite its radical roots, has culturally evolved into an institution that is often seen as synonymous with high art and pretentious attitudes. “I feel the power of dancing has become diminished in jazz. It’s become very elitist. Ourselves, Yussef Dayes, Nubya Garcia and a lot of other people in the scene, have brought dancing back to the genre,” says Ife. Not since the acid jazz movement has there been a looser idea of what jazz is and can be, but most importantly where it can dwell.

The acid jazz movement began life in the '80s as an evolution of the “jazz dances” hosted by pioneering DJs like Gilles Peterson, Paul Murphy and Chris Hill. These were events that played hard bop, samba, Latin jazz and selections from the Blue Note catalogue in between chart funk, soul, disco and house. By the '90s, the phrase had evolved into an ambiguous genre category referring to artists who fused jazz with funk, hip hop, rare groove, house and breakbeat. Acts like The Brand New Heavies, Incognito, Us3 and Jamiroquai would be among the most notable, and come to epitomise the sound. The movement even spawned a same-named record label founded by Peterson and Eddie Pilar.

Read this next: How the jazz-dance underground broke into the London mainstream

Though unfairly obscured and a victim of cultural erasure today, echoes of that fabled time certainly exist in the work of today’s contemporary British jazz scene. “I didn't have them to look up to because I didn't know what it was until recently. It's only now when I see things from Jamiroquai, I can see it's not far off from what we do. I feel like some of the ingredients that gave us acid jazz, we accidentally used them too. We listened to people like Goldie and Channel One Sound System and then came up with our own brand of jazz.”, Femi notes.

In subsequent years, the genre has been given the space to be demystified, move away from modes of respectability and re-emerge as a youth-focused sound. With many of this generation’s talents being of Caribbean and West African descent, naturally they have a preference for bottom-heavy sounds and incorporate those forms into their masterworks. “We like Afrobeat, reggae, hip hop, grime, dancehall, jungle and funky house but we mix it in with the intellectual side of jazz and all the interesting things you can do with rhythm and harmony. It was only natural that people would dance to our music. We’re still London boys at the end of the day,” Ife says.

The plan when putting the album together, however, wasn't centred on a pre-occupation with what genres they’d fuse in. Those came naturally. For Femi, constructing songs that bore the atmosphere of their live shows was the main task. “The agenda was how do we get the feeling of Ezra Collective live but the sound of the studio. I wanted it to feel chaotic. I wanted it to feel like you're in the room,” he says. The Beatles’ rooftop sessions for ‘Let It Be’ and Fela Kuti’s ‘Water No Get Enemy’ are cited by Femi as key north stars for this, but he's most enthused when speaking about how gospel musician Kirk Franklin set the standard for striking that specific balance. “When you listen to ‘The Nu Nation Project’, all you have to do is close your eyes and you’re in the church. It's so crisp. It doesn't sound like a live record, but it feels like one.”

Read this next: Almighty influence: Why Gospel music deserves more support and investment

Admirably, Femi also references Ezra’s own back catalogue as a counter example. “‘Where I’m Meant To Be’ is a beautiful studio album, but it doesn't feel live. When I listen to ‘No Confusion’, ‘Ego Killah’ or ‘Siesta’, I think they’re brilliant songs but it doesn't feel like how we do it live. This new record creates that blend more powerfully. It’s another galaxy,” he says.

As musicians of their ilk and pedigree, it’s not surprising that artistic growth remains a priority with each record. Yet with their win at the prestigious Mercury Prize and a Top 30 placement on the UK Albums Chart only recently in the rearview, the lure of repeating a winning formula could be tempting. “Fortunately, Femi had the foresight for us to start working on the album way before all the accolades. By the time we had been awarded with the Mercury, we had already nearly finished recording,” Mollison reveals. It might be too soon to declare their previous album as “career-defining” but it wouldn’t be hyperbole to say it set the wheels in motion for an incoming imperial phase, and not just for them, but for potentially their scene at large.

The win at the Mercury Prize was historic as it marked the first time a jazz act had the honour bestowed onto them in its three-decade existence. A banner and milestone moment for a generation of musicians who’ve come to symbolise a new golden age in British jazz. Adding to these strings on their bow, this November they will become the first jazz act to headline OVO Arena Wembley. Some would say Ezra Collective are quickly becoming the act central to the scene earning more cultural cache in mainstream spaces, but the boys themselves are too grounded in the lineage they come from to get absorbed in the hype. “It's a deep feeling of gratitude for the amount of heavy lifting that was done for us to be in this position. It’s like being born into a family business that your great-great granddad started, and now it's your turn to take the baton. You don't feel you've created something; you're just grateful for what came before you”, Femi says with an emphatic earnestness.

Cognisant that they stand on the shoulders of the likes of The Jazz Warriors, Jazz Jamaica, Empirical, Courtney Pine and countless others in British jazz’s genealogy, Ezra Collective understand there’s an inherent responsibility levied onto them. In addition to Femi’s own frequent work with youth organisations and schools, Ezra have remained steadfast in paying it forward by inviting students from youth music charity Kinetika Bloco to join them onstage at their shows at Glastonbury, Royal Albert Hall and Hammersmith Apollo. “Our aspirations are far more in the direction of creating a legacy that inspires people. That’s the deepest level of success,” Femi avows.

According to Gary Crosby, member of Jazz Warriors and founder of Tomorrow’s Warriors, the jazz education organisation where Ezra Collective first met, these actions are an extension of how his former students were reared. “Our ethos is ‘Each one, teach one’. We expect those who come through the programme to give back to the next generation by becoming music leaders themselves, leading ad hoc sessions, and passing on their experiences,” he says. “This has become a sustainable model that is distinctive to Tomorrow’s Warriors. The way Ezra have spread their success to others shows they are committed to the nurturing of new young practitioners.”

It's that humility and consistent engagement with community work that allows the band to retain their integrity and focus on maintaining the purity of their art. Even in the face of mounting commercial pressures and expectations. “You always want to feel you're moving forward, but you've got to see forward as a musical and creative thing, not a numbers thing. If it became all about going number one and it doesn’t, suddenly you've taken away from something that should be a deep moment of pride,” Femi says. This understanding, however, is not just shared between the band themselves, it’s a line of thinking that extends to their wider team. Corroborating over email, their manager Amy Frenchum says, “What motivates me and keeps me pushing forwards is aligning with what a personal definition of success is for the artist on their own terms. Goals and ambitions have to be personally nuanced to keep you human – otherwise you just get lost in the industry machine of comparing stats and figures – when that shows no reflection of how personal and different each artist’s journey is.”

No matter how they arrive there, the third album in a musician’s career is typically marked with chatter about how it's supposed to “solidify” their standing or “consolidate” their previous success and acclaim. When grouping all of Ezra Collective’s album titles together, there lies a narrative in between the lines verging on the allegorical. “With [debut album] ‘You Can't Steal My Joy’, there was definitely a feeling of us being ignored. Very much us against the world kind of feeling. Then with the last album [‘Where I'm Meant to Be’], there was definitely more of a grounding in who we are and what we want to portray,” Femi reminisces.

For the Ezra boys, the new album is deeper than just an expression of joy. It’s the culmination of a residing inner peace and security that supersedes all understanding — and doubling down on that feeling, no matter how it looks. As Femi asserts,“There’s something so beautiful about looking mad to everyone else, but only you know how real it is. Scrapping the need for self-assurance and just being completely self. That’s the place I feel Ezra Collective is in right now”. Unless we refuse to heed Ezra’s call and surrender to the intrusive nature of insecurity and indecision, this can be a destination within reach not just for them, but for us all.

‘Dance, No One’s Watching’ comes out on September 27 via Partisan Records, pre-order it here; get tickets to their Wembley Arena show here

Sope Soetan is a freelance music journalist, speaker, publicist and researcher, follow him on Twitter