Features

Features

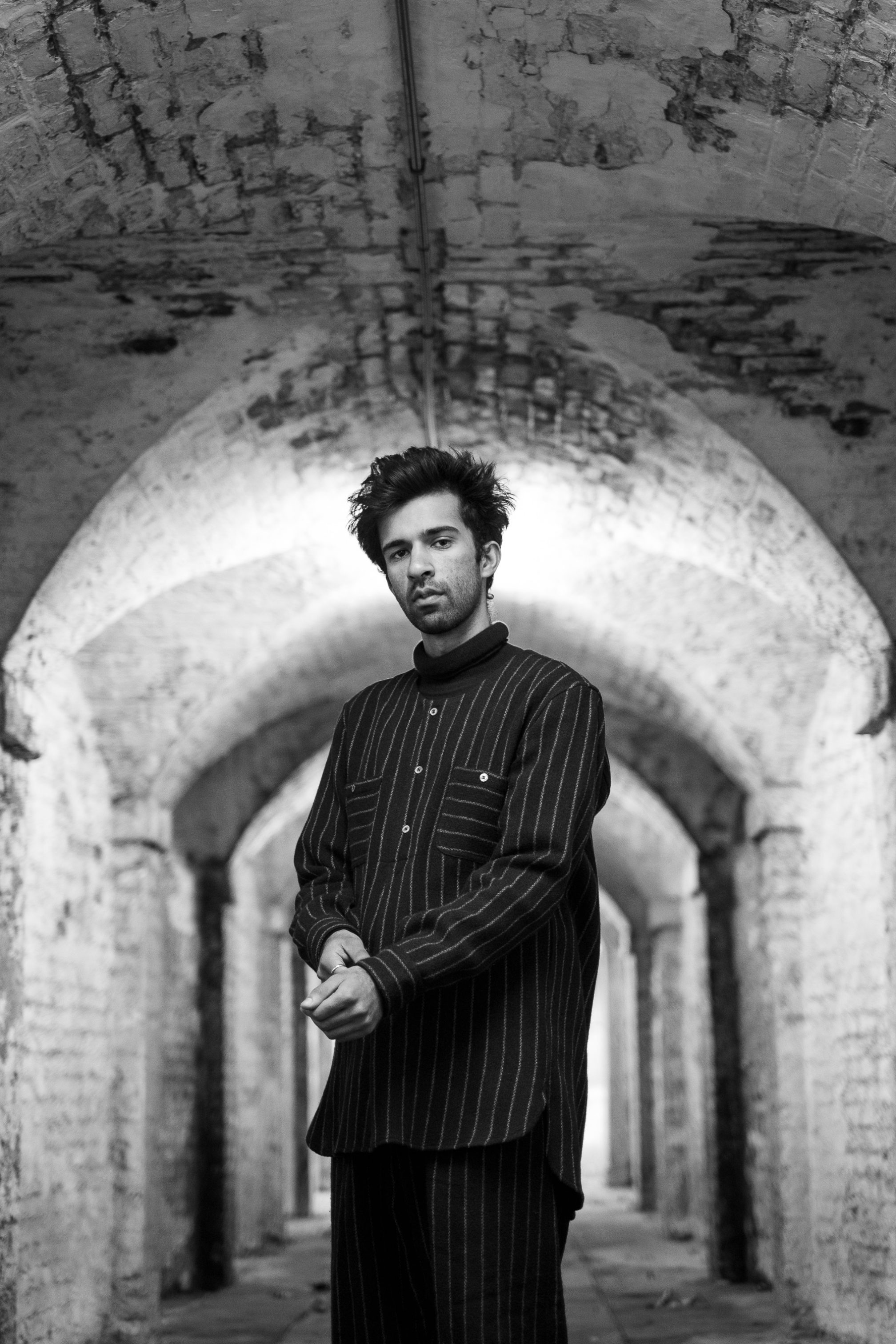

Haseeb Iqbal: "DIY spaces are at the root of so many influential music scenes"

Seb Wheeler talks to Haseeb Iqbal about his debut book, Noting Voices, and the crucially important independent venues, festivals and events that it documents

Haseeb Iqbal has been immersed in the new UK jazz movement for several years now, frequently having epiphany-inducing moments to the likes of Sons Of Kemet, KOKOROKO and Ezra Collective.

These mind-blowing moments have often taken place in DIY or independent spaces, venues and festivals, with the events organised by promoters who – just like the musicians and the fans in attendance – do it strictly for the love.

In his debut book, Noting Voices: Contemplating London's Culture, Haseeb joins the dots between the artists, promoters and fans who have built a burgeoning scene around the sound and energy of new UK jazz and shines a light on how important to and influential on wider culture grassroots movements such as this are.

Read this next: How grime and afrobeat is influencing UK rap

Focusing in on the DIY infrastructure that has emerged in London, Haseeb dissects this wildly creative and incendiary jazz wave in relation to the British arts institution, gentrification and education and makes a passionate call for the spaces where musicians like Shabaka Hutchings and Nubya Garcia practice, play and mentor the next generation are vitally important to UK culture on the whole and should be respected as such.

Get acquainted with his breathless excitement for this music its utopian potential in the Q+A below, where he discusses DIY scenes and spaces, why they should be cherished and nurtured and a vision for live music after lockdown.

Noting Voices started as a series of radio shows. Why did you decide to have these conversations?

Mare Street Records was a podcast that I started with a couple of friends, which I host. It centred on the London jazz scene, so to speak, and that's the musical scene that I've grown up with and [being played in a] lot of the spaces that I was going to from a super young age. And then this media hype started to generate towards the end of 2017 and I felt like a lot of the outlets that were covering it weren't really giving true justice to it. A lot of it centred on the culture, but it didn't necessarily centre on the spaces that facilitated that culture. Mare Street Records was an opportunity to relaxedly, through a conversation rather than interview format, just take it back to the root of where this culture came from, which was the spaces and the figureheads that spearheaded them. So Marina Blake, who started Brainchild festival, Lex Blondel, who started Total Refreshment Centre, Wayne Francis who started Steam Down, Slam The Poet who ran Steeze, Errol Anderson who started Touching Bass. So the book focuses on those five chats and looks at the importance of space forming community and the imperative relationship between community and space, and how culture stems from those ingredients.

Viewing space in terms of music and youth culture is quite a philosophical take. When did you first start looking at venues and dance floors in this way? In terms of these spaces being important and more than just a function for selling alcohol on a Saturday night?

When I started going to these spaces, there was clearly something different to anywhere else that I had been, which is what a lot of what I write about in the book is about, that theme of eliminating hierarchy and the lack of hierarchy that exists within those spaces. The festivals that I'd been to before were Reading Festival, Wireless and Lovebox, which is that mainstream consciousness, which is what everyone goes to. So you go to those and you're offered entertainment in a way that you are the consumer and they are the providers and there's a barrier, there's a VIP section, there's security guards, you are physically and metaphorically separated from [the artists playing]. And that just doesn't humanise the talent that you're seeing.

First time I went to Brainchild with a couple of friends when we were 17 years old, there were no VIP areas, everyone camped together, automatically there's something that you could sense. I wasn't at that point contextualising this entire idea that's in the book, but there was definitely a feeling of what's different. The same at Total Refreshment Centre as well, the relaxedness of it, that person who's performing is just going to come and sit in the crowd and what that chilled-ness and that lack of structure and that lack of spacing out people allows the artists to become better, it allows them to chill out more and it allows the people to enjoy it in a much more relaxed way, you're not conscious of what your role is there, your role is fluid.

The first time I went to Brainchild it was like, I've never experienced anything like this. I feel so comfortable. And I feel like I can be whatever version of myself I want to be here. It was just a rebellion against what I was familiar with. In 2016 in the Steeze Cafe at Brainchild I saw Puma Blue followed by Ezra Collective followed by KOKOROKO play to not that many people and that was the evening that changed my life. It was the first time I'd seen live music in that way: just being next to the instruments, seeing the power of physical instruments to evoke a feeling within you in a direct setting where there's no stage and there's no barrier in between you and the music. That reciprocal exchange just gave me a feeling that I've never felt before.

Read this next: Meet Nicholas Daley, the man dressing the UK jazz scene

The spaces that you mention in the book are driven by a love of art, culture and music. These spaces and these crews are probably not doing it for the money in the first instance. Given that these spaces aren't driven by money, how do you think that they can survive in quite a cut-throat landscape long term, but retain that magic of not having security, not being focused on beer sales, not selling 1000 tickets every week?

The longevity stems directly from the ethos and the philosophies of the space and the philosophies of the people that spearhead it. Brainchild festival has never had any sponsors, they've been sponsor free since they've started. That's been a key element for Marina [Blake, founder] to retain, even when times were really tough, and they were losing money, she stuck with that because she knew that that would change the feeling within the festival. 1 per cent of their budget a couple of years ago went on to marketing, it's now slightly increased, but it's always been word of mouth and what that's meant is that people are going to come if they've genuinely been told by a friend that it is so amazing. And that's what happened to me: the first time I went, three of us went, the next year, six of us went, the following year 15 of us went and in 2019, 60 of us went – it was nuts. And what that means is people are there for the right reasons. The focus of people like Marina is on the craft, it's on the space itself, rather than the image.

The same people will consistently come back year upon year because they know what the values of the space are. And they don't need to see what the line-up is going to be because they trust the philosophies and they trust the ethos of how Marina books, who she wants to bring in and everyone knows that it's going to be an incredible space. So I think when you've got the people there and the people who want to come back, the longevity kind of looks after itself. When it comes to sustaining a DIY entity, which is a lot harder, I know [the festival has] been working out a long-term financial plan as to how they're going to sustain the festival. But what I also write about in this book is that all of these personalities that front these spaces, they're constantly searching for new energies, they're never stuck in a way that is "this is right, and this is how it's gonna happen". And something that I write about in the book, which looks at that, is when this jazz lot started to get really successful after 2017 Marina bugged out and she was like, who am I going to book? And then she was like, right, the repositioning of these artists is making me reconsider what are our values? If Brainchild is a space for emerging artists and these guys are now too expensive to book, I need to recalibrate what our philosophies are and look to the next generation. I think that's been a really important part of these people taking that philosophy and remembering it and staying rooted to who they are.

There's a powerful section about gentrification in the book, as well as grassroots scenes, not being given due support for the art they create, what structural change should occur to safeguard venues like TRC and give support to people who are providing a platform for new talent and culture?

If you're used to going to the Royal Festival Hall or the Royal Albert Hall and you watch BBC Proms to consume your culture, you might forget about Steam Down being part of the picture, or Brainchild festival doesn't really occur to you. One of the things that I write about in the book is the fact that in the last year, we've had KOKOROKO perform on the BBC proms, we've had Sons Of Kemet headline Somerset House, we've had Ezra Collective performing on the West Holts stage of Glastonbury, Steam Down have performed on Later With Jools Holland – suddenly these people who have been cultivated and nurtured through these grassroots spaces are now entering the mainstream consciousness through these massive platforms. So, if the people in these Regents Park houses are going into the Royal Albert Hall to consume their culture and they're seeing KOKOROKO and really enjoying that, that culture has come from somewhere. And when accessing it on a mainstream level, I think it's easy to forget about the root of it, and the source of all these cultures. These people wouldn't be playing for these lot if it wasn't for these DIY venues. And I think there's a really interlinked element between grassroots and mainstream that people forget about. Even [a band like] Oasis – they were found playing pubs by Alan McGee from Creation Records. It is very rare that you're gonna see an important artist who hasn't passed through these grassroots spaces.

I think there needs to be a communication between the mainstream channels through which we consume culture and grassroots and that's a really hard thing to make do and I think a lot of people in the grassroots sector are pessimistic about that being a thing. But I think if we can build a level of communication between the two, hopefully people can become more aware of where this culture is coming from. The government can understand that these spaces are truly important, not only providing a large part of mainstream culture and allowing festivals like Glastonbury to pick their headliners and Somerset House and BBC Proms, but also they see it as a way of young people staying out of trouble and having an identity to mould and having a purpose to follow, and seeing initiatives like Tomorrow's Warriors as truly important. It's about allowing young people opportunities and community-based sectors and community-based environments to find their identity in an un-pressured, useful and supportive environment.

Community participation, spontaneity, DIY, these are all elements of jazz. Is it a coincidence that a lot of the book takes place in the context of the UK jazz scene?

For years I was there, I was feeling all of these feelings and being in these environments, like "what is it that is making me come to Steam Down every week?" What jazz has, and what live instrumental music has, is that directness, that reciprocal exchange between the musician and the listener. What I mean by that is, you are influencing how the musician in front of you is playing: if you're screwing your face more or losing your shit more or you're sweating more, they're gonna blow into their sax more, they're gonna hit their drums harder, they're able to channel that. Femi from Ezra Collective says that if he's playing at Ronnie Scott's but has been listening to Giggs that morning, Giggs is going to come out on the drums! He can let that loose. And if someone's looking at him, he's going to evoke that feeling and then it's going to bounce back to the audience. And that's the thing about jazz, it starts somewhere but neither party knows where it's going to end, it's totally based off that reciprocal exchange, and if there are three people in there, and they're sitting down, they're not doing anything, the gig's probably not going to be as energetic, maybe that's fine, maybe it's more of an emotive gig, but it's the listener element, it's the participating element and the thing about these spaces is there's no stages. You'd never go to TRC and see an elevated stage. Brainchild's main stage is a tiny fucking stage, you're right in it with these people. Steam Down, you're in this arched venue, you can't even tell who are the musicians and who are the dancers, and when you get rid of that physical barrier, that directness is able to reach a whole new level where it's so much easier to access each party and each party is so in the thick of it.

You focus on mentorship and transference of skills in the book. How can both elders and youngers in scenes get more involved with this?

It comes back down to the space in my opinion. We're at a really interesting intersection right now because I've obviously grown up with this music and it's now all hitting the mainstream over the last couple of years, it's gone nuts and we're at the point where the next generation is coming through, literally right now. You've got kids now who are seeing these musicians play, who are on the same path as these lot. They're saying, "I want to do that" or "I want to be like them, where am I going to go?" There's this new thing that's started, actually started in lockdown last year, an outdoor park jam, called the Sesh Brehs. I started going and I was the oldest one there at 21 years old! It's quite a mad feeling when you've got all of these incredible musicians who are doing their shit, shredding it, and then you had Mansur Brown who popped down or the older heads who were also there and it's like, the ego doesn't get in the way of a lot of these people and that's what I've got most respect for. Mansur has done all of the shit that he's done and hit the level that he's on yet he's still coming to Hilly Fields on a rainy Tuesday to look at these musicians who are playing and he might jump on the guitar and play a little bit and they're all playing. It's all rooted in the love of music, this scene, and it's all come with that.

They [the leaders of this movement] are used to the grit of it. They were used to going to Steeze every single month, going to Good Evening at the Royal Albert started by Tom Sankey, still runs it, puts his heart and soul into this night, every single Sunday a new band will be playing. These lot became obsessed with the craft, they became obsessed with going to the pub every month, or every week or jamming with each other in someone's garage. You need to be putting in five hours a day for the last few years to be built up at your craft. And I think when you're seeing these people now who are coming in, it's taken them so long to get to where they are, that they now know how to keep it because they didn't get it so instantly. And when you've got these young musicians who are truly looking up to them, and they're getting told directly from that mentorship angle, "this is what we did". Whether it's Tomorrow Warriors, free workshops, that's something that so needs to be protected. A lot of the new jazz musicians go there to mentor and they're not elevated from you. There's no ego in the way, they are humanised, and when these people are humanised in front of you, you think that you can create what they're creating, and that mentorship makes it so much more feasible in the mind of these young musicians, and the space again is the root of all of it.

Read this next: Steam Down is at the forefront of the UK's new jazz age

This feels like a powerful document as to how to proceed once the lockdown is lifted, what would you like to see change in terms of how venues and scenes are run and protected?

Protected is the key element isn't it? We're at a point now our entire interaction with the outside world is often through the realm of the screen and we're separated from the people around us and we've lost that human touch. So, the human desire is definitely going to be there, to get back into the room, to sweat with people, to hug each other, to dance with strangers – all of those things, it's a human need.

Just like animals have their primitive urges to come together, we have the same urges and technology had already been an infringement on that from before this time [the pandemic] and if anything, the people who were more consumed by that have now clocked that they need human interaction in a way that all of us do. And no one's an exception, we all need it. Some might crave it less or more, but we all need it. It's our oxygen.

So I think that human desire is going to be there. My only concern is that the government, because of the amount of money that they've spent, are going to see the arts as very low down on the priority list when it comes to what to inject funds into and how to save money. And they're going to be getting the axe. So I think we should prepare ourselves for some of that, because it's important to stay realistic, despite the optimistic energy [around the lifting of lockdown] that is brilliant. If there's one thing that this book celebrates, it's grassroots energy, grassroots activism, it's the fact that all of these laws have not been reliant on bigger structures, so let's keep it simple: Go to your local bars, go to your local spaces, be like, "listen, you've been closed for a year and a half, give me once a month, or a Tuesday evening residency, and I'm gonna bring some sick DJs down, and I'm gonna make a night happen for you, and you're gonna make some money on the bar, and give me 10 per cent, but let's just do it for good energy." People are going to be dying for new ideas, people are gonna be dying for new energy, in a way for all the people who felt like they were a bit behind before all of this, who felt like they were kind of the receivers and not the givers, this is a time to offer, this is the time to come in with your energy and not be scared of rejection. The minute you're scared of rejection, you're going to lower what you can do by 90 per cent – don't let that be a factor. Go to different spaces, go to different people, make friends with the people that run these spaces and say, "I want to bring something to you."

As I write about in the gentrification section with the jerk chicken guy, look out for the local community, get the local community down. Think of ways of collaborating, think of ways of not just centring ourselves, but bringing other people in and think of those who have struggled and bring communities together. So make it happen, be innovative, be bold, think the unthinkable, do shit that you couldn't think could actually happen and I think we can all do that and people will be wanting it. So let's not be scared.

Noting Voices: Contemplating London's Culture is out now via Rough Trade Editions

Read this next: The under 30s running the most exciting music festivals around