Features

Features

How the Dance Music Industry failed Black Artists

DeForrest Brown, Jr. surveys the last three decades of the dance music industry to figure out what went wrong for Black artists

2020 hasn’t been kind to the dance music industry, though much of the resulting damage has been self-inflicted. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic set into motion a series of complications that would surface many of the industry’s structural shortcomings. Recently we’ve seen Kevin Saunderson – one of the founders of the techno sound – come forward in an interview with Billboard magazine stating that “the scene is [still] failing Black artists”; The Black Madonna reluctantly and spitefully changing her name to The Blessed Madonna in response to years of criticism from Black voices, and the closing of Dutch club De School in the wake of accusations of racial profiling and sexual harassment from their security staff and debts caused by the pandemic. At the same time, protests around the world over police killings and brutality of unarmed Black people such as George Floyd, Amhaud Arbuary, Breonna Taylor, Rayshard Brooks, and Elijah McClain as well as Jacob Blake and countless other unarmed Black people in the United States have forced sections of dance music to begin reevaluating how they’ve previously mishandled situations of race and inequality. Most recently, a dispute over Dutch record label R&S’s handling of Black Lives Matter with producer Eddington Again led to the label's founder Renaat Vandepapeliere making a public explanation after he was accused of using discriminatory language.

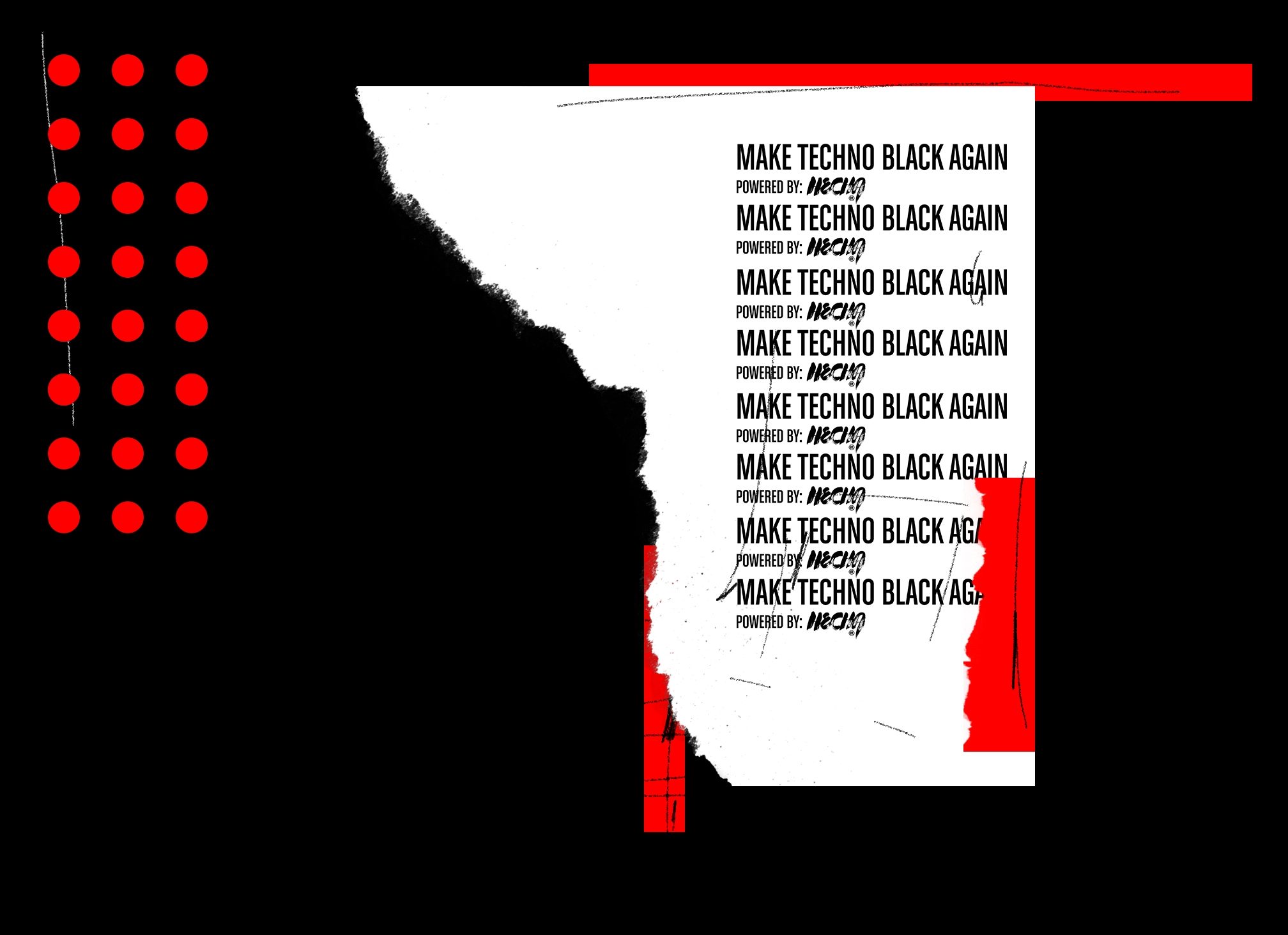

In December of 2018, I signed to Planet Mu records as Speaker Music after two releases with sound artist, composer and writer Jon Davis, who performs as Kepla on PTP as a way to engage with the problematic cultural and economic dynamic of the music industry as both a participant and critic. Along with this, I began working as a representative of the Make Techno Black Again campaign, powered by HECHA / 做 which celebrates the origins of techno and its roots in cities like Detroit and the African-American working class experience as well as donating 50 percent of its revenue to Teen HYPE (Helping Youth by Providing Education), a Detroit-based youth arts nonprofit. Inspired by NYTimes reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones’ 1619 project, which re-examines the horrific and criminal enslavement of Africans in the United States, I wanted to lay out a historical project through my writings and works that hopes to gather Black people with a phrase that implies that techno is a cultural expression and movement that deserves to be reclaimed into our collective memories.

Make Techno Black Again

The challenges that Black musicians experience are more or less built into the system. I often say that you can’t talk about techno, or Black music as a whole, without addressing the transatlantic slave trade. Regardless of how you look at it, Black people are a central point of labor extraction in the United States and the rest of the world mirrors this aesthetically and ideologically. From experience working in the music industry (and as a former East Coast Editor at Mixmag), I know that publications, labels, promoters and festivals are not inclusive in any way, nor are they interested in tangibly upholding a standard of diversity. Kevin Saunderson asserts in the aforementioned interview with Billboard that “the problem is that many of the people in power in these companies don’t really care.” He continues on to say that, “They’ve got a responsibility to correctly represent the culture they’re profiting from, but the responsibility in their mind is only to make money.”

The dance music culture industry as we know it has benefitted and is built from a cultural theft and estrangement starting with Neil Rushton's compiling of Detroit tracks on the ‘Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit’ compilation with Derrick May on Virgin’s sub-label 10 Records in 1988. This release introduced the term techno to European listeners, but the recognition of the sound's origins in middle class Black America did not spread as far or wide. In the liner notes for the compilation journalist Stuart Cosgrove named Juan Atkins, Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson the Belleville Three, but subsequently excluded the stories, lives and inspirations of the other musicians who contributed to the album such as Eddie Fowlkes, Anthony “Shake” Shakir, Blake Baxter and Members of House (whose members Mad Mike Banks and Jeff Mills would go on to found Underground Resistance). The innersleeve notes opens the inventors of techno’s origin story with: “Think of Detroit and you automatically think of Motown, but be careful not to think too loud because the new grandmasters of Detroit techno hate history.” Today in 2020, it is important that Black creatives stick together and discuss where and how we have been positioned amongst our white and European peers.

During this year’s Dweller Festival celebrating Black electronic musicians and culture, Make Techno Black Again hosted a panel with Frankie Hutchinson (founder of Dweller and co-founder of Discwoman), DJ/producer SYANIDE and cultural producer Camille Crain Drummand, discussing “who does techno belong to?” During that talk, I made a number of blanket statements in a heated “town hall” meeting that I would like to explain more clearly here. For 6 months in 2016 I was employed as Mixmag’s US East Coast Editor. At the time, the job for me was a big deal financially, and a clear advancement on my resume. Specifically, this position would allow for me to advance from being a freelance writer to a staff worker with a potential living wage and regular income. By outsourcing labor and expertise to third-party self-employed workers, publications are able to manage a seemingly endless pool of writers who exist as content generators with no rights, representation or protection against corporate entities. With this assumed job security, I found a new challenge in that I was the only Black person on the US editorial team despite the existing diversity among the wider American staff. My employment at Mixmag felt tokenistic and diminished almost immediately. Despite holding an editorial title, I often felt as if I was expected to be humble and accept a role of only writing news stories and the occasional album/single review as assigned by other staff members. Eventually, I was unceremoniously fired for “not being a fit,” though there are only two articles from my time at Mixmag that are representative of what I could have contributed to their platform: an interview with Fatima al Qadiri on the subject of police brutality and a profile of the underground Philly-based ATM collective (DJ Haram, SCRAAATCH).

Mixmag opened offices in Los Angeles and New York in 2015 in hopes of tapping into the burgeoning US dance music market. Despite the financial collapse in 2008, the EDM Boom and a flourishing music festival culture including brands like Coachella and RBMA (Red Bull Music Academy) created an entry point for European brands, artists and consumers who had mostly existed in an insular industry structure much smaller than that of the American pop music machine. In an article published earlier this year by Rhizome on EDM, speculation, and finance, writer Alexander Iadarola considered the connection between economics and dance music from a purely American perspective, writing: “The height of EDM’s popularity was carnivalesque in the extreme, and the EDM moment was characterized by unbridled big business, high-intensity partying, and escapism.” In the United States, dance music that doesn’t fall under mainstream EDM popularized by Skrillex has been largely non-existent aside from situations in which it has been absorbed into the mainstream subconscious through television programming like Adult Swim or subtle influences in popular music. American consumers through the 2000s were more likely to listen to pop and indie music precisely because publications like Mixmag tailored the narrative of dance music to the UK, and European labels subsequently wouldn't distribute widely in the US out of fear of having to compete against America’s massive music industry. In a 2015 interview with the Independent, Mixmag Global Editorial Director Nick DeCosemo commented on how the magazine is very protective of what they consider to be “true” house music as Mixmag began to grow its presence in the US market, "LA without a doubt is having a moment; friends of mine say it feels like London in 1990, 1991 [...] Every week, another tranche of European DJs arrives in LA."

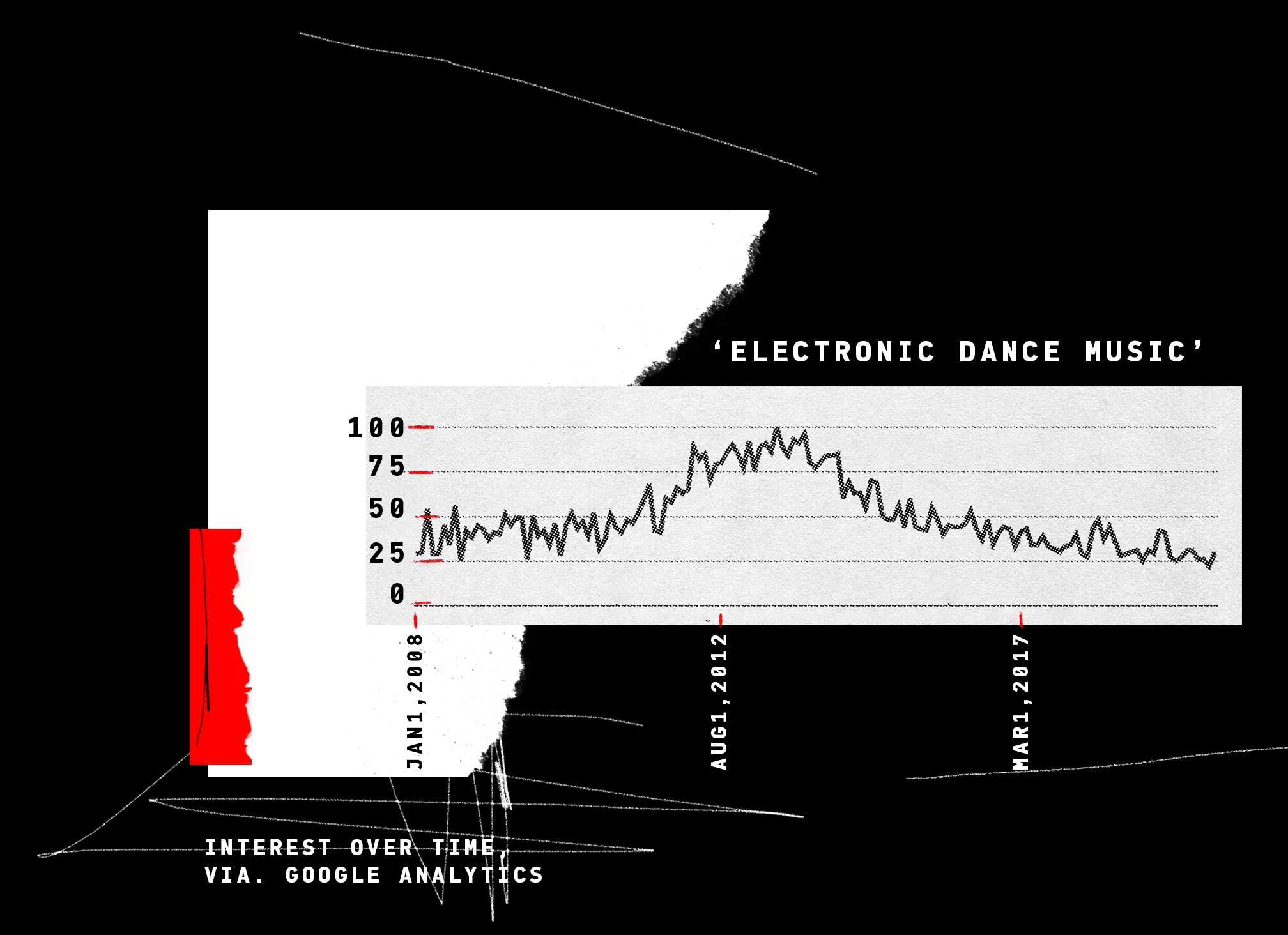

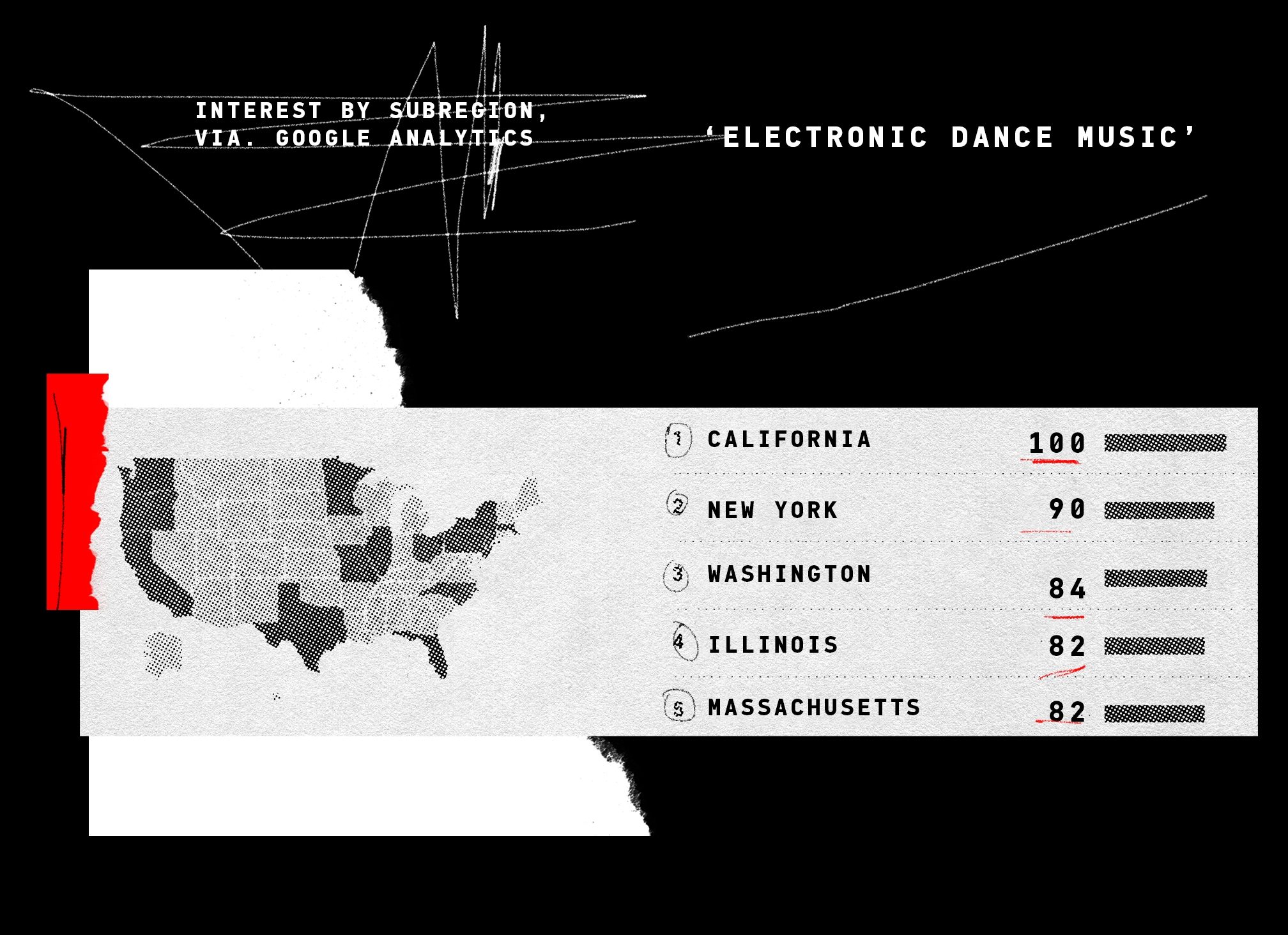

For a previous writing on “how platform capitalism devalued the music industry,” I presented two Google trends charts laying out the level of general interest that Americans have shown in electronic dance music from January 2008 to February 2020. A brief peak in interest can be seen around August of 2012; but when considering the subregional trend chart, dance music is mostly restricted to coastal states, often associated with being economic generators for the United States between Silicon Valley, Wall Street and their varying elite universities.

The goal of my article was to write into the dance music narrative an inherent cultural rift between the US and European understanding of race, culture and value. When the entire history of the Western world and how Africans would even end up in America and throughout the global diaspora is included, the dance music industry begins to look like the result of a contemporary stage of colonialism in which a large population of white/European leisure class citizens with multinational access repeatedly “discovered” and absorbed diasporic and indigenous culture into an unviable, but booming economic venture. Techno music was always about the idea of being involuntarily subsumed into a commerce-oriented society. Detroit’s two greatest exports were cars and music, and the city itself was a blueprint for the potentials of 20th century urban planning and musical development across the world. Detroit would later be out-produced by German and Japanese automotive manufacturers and fall into a financial depression, prompting “white flight” to the suburbs leaving behind Black workers who had fled north as an escape from the white supremacist domestic terrors of the segregated Jim Crow-era of the American Southeastern states.

The term techno is a prefix of the word technology, but could be further extended to encompass technocracy, meaning a society or government run by technical experts. The properties of a technocracy was explained in detail in the 1980 book The Third Wave by futurist and businessman Alvin Toffler, which a 19-year old Juan Atkins read in a high school class called “Future Studies” before developing his vision for techno music. Detroit was the example of what a technologically enhanced city of the future could look like, and its collapse showed that something was very wrong with the way in which white people were conceiving of and designing a future for Americans—the resulting economic disparity and race riots took the future away from its Black population. This is a frequent way in which white people disenfranchise and harm Black communities. Cybotron, Juan Atkins’ electronic funk band with Rick Davis, a reclusive Vietnam veteran crafted the sound and concept of techno in the early 80s together through interpersonal conversations with a shared vision of a future where they as African Americans would be able to live in a city and nation that acknowledges the traumas of the past as well as their effects on the future.

Beyond the dance music industry having a problem with understanding race, it has a problem with understanding how it has structured itself to ensure that it and every person involved with it will be susceptible to racial and categorical biases. A letter addressed to Resident Advisor and “the rest of the UK music press” from Roshan Chauhan, aka R.O.S.H. took the journalistic integrity in the dance music industry to task. In a sweeping 14,000 word essay Chauhan outlined examples in which music journalists neglected to fully define and uphold terms and industry standards while subjecting others (oftentimes Black people and people of colour) to arbitrary definitions and narratives. The letter wove together quotes from reviews and artist interviews in an attempt to breakdown how press absorb and contextualize genres while obfuscating cultural backgrounds in the process. For the July 28 issue of his newsletter First Floor, music writer Shawn Reynaldo penned a one-sided conversation on how plausible it would be for majority white-run and staffed publications to employ and support its Black demographic. Reynaldo writes that the discrimination and racial bias in the music industry needs to change, “but change isn’t all that feasible when the site’s primary revenue streams (i.e. ticket sales and advertising) have all but dried up, freelance budgets have been cut and much of the staff has already been furloughed.” In a more recent letter on September 15 called “the Music Industry Isn’t Built for This,” Reynaldo admits that, “while music media outlets have done their best to expand their focus, be it discussing the impacts of COVID-19 on the industry or reporting on how the Black Lives Matter protests have reshaped the cultural landscape, the hard truth is that, by and large, even the most veteran music journalists are woefully under equipped to properly tackle these issues.”

In essence, 2008 to our present industry collapse could be characterized as the result of music publications attempting to run websites like small online ad-sale startups to capitalize on an influx of a global Millennial consumer demographic in metropolitan cities and a catalogue of intellectual properties throughout dance music history. Even platforms like Vice attempted to tap into the seemingly growing demographic by launching its short-lived dance music vertical Thump. After a decade in the American market, a pandemic and social/political unrest, the dance music industry is at a stalemate. For the unforeseeable future, clubbing will remain an idea in abstract because of the pandemic. While the industry is experiencing this pause, I’d like to look backwards.

Mixmag, the “Dance Music Bible”

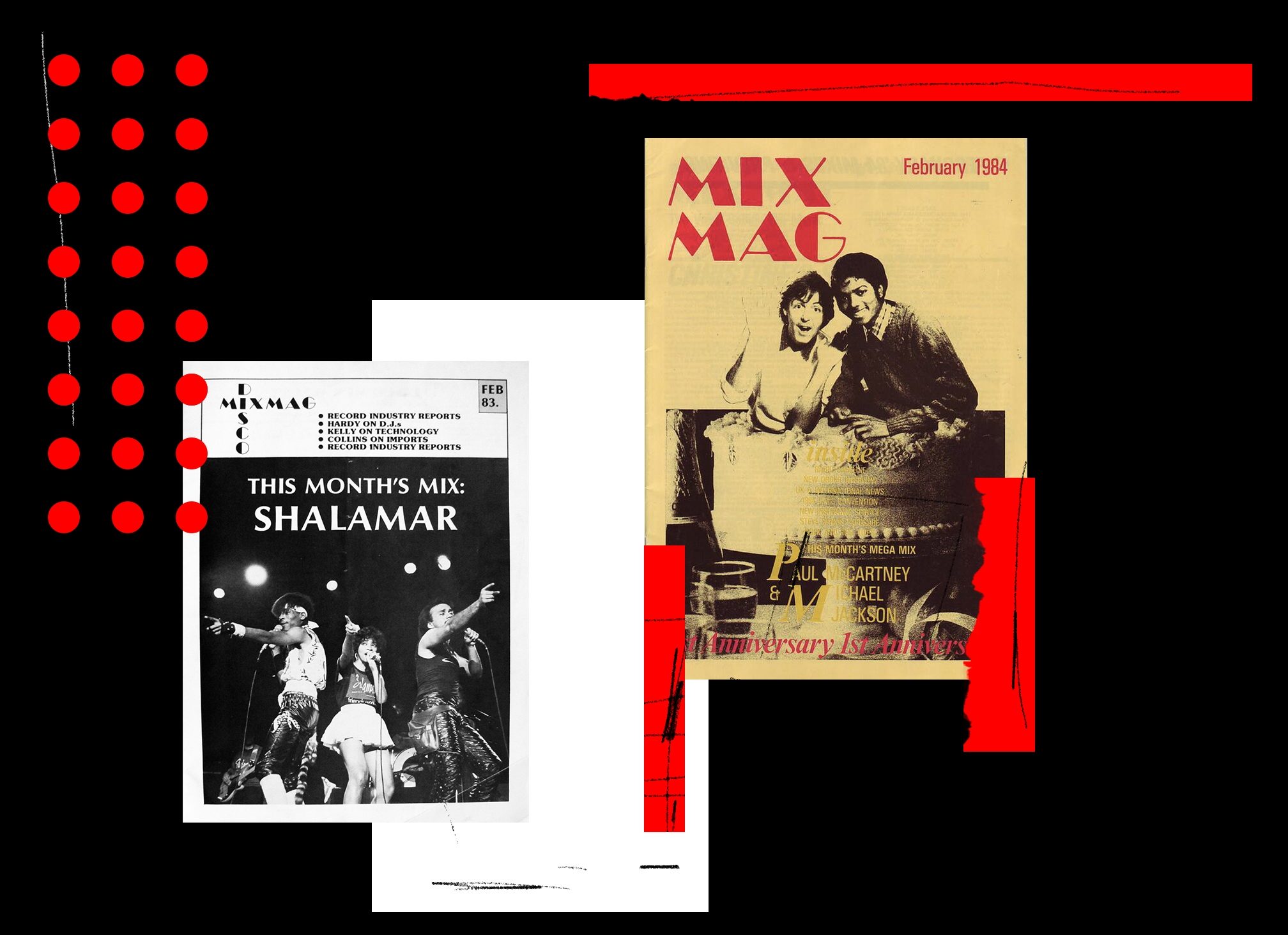

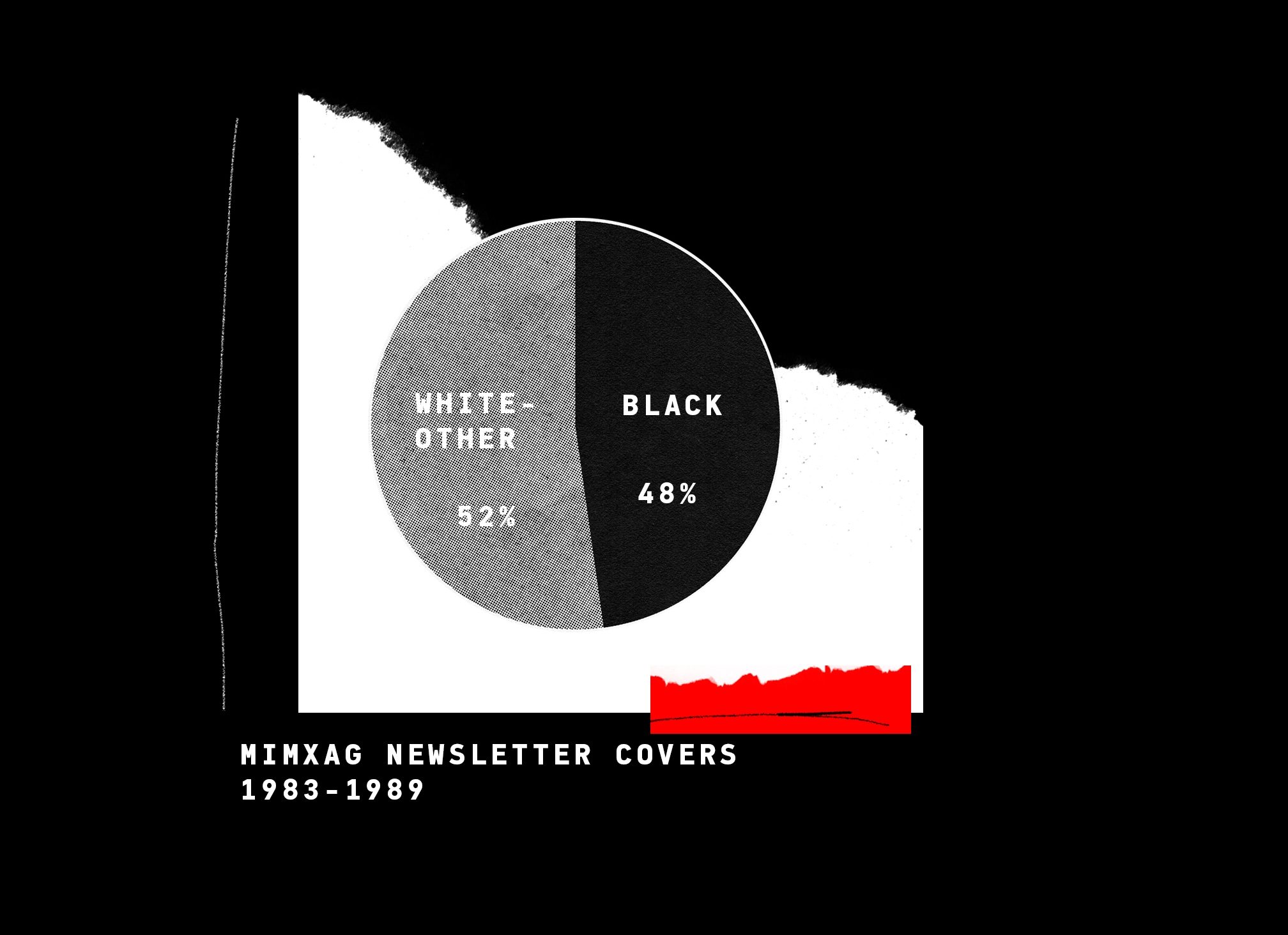

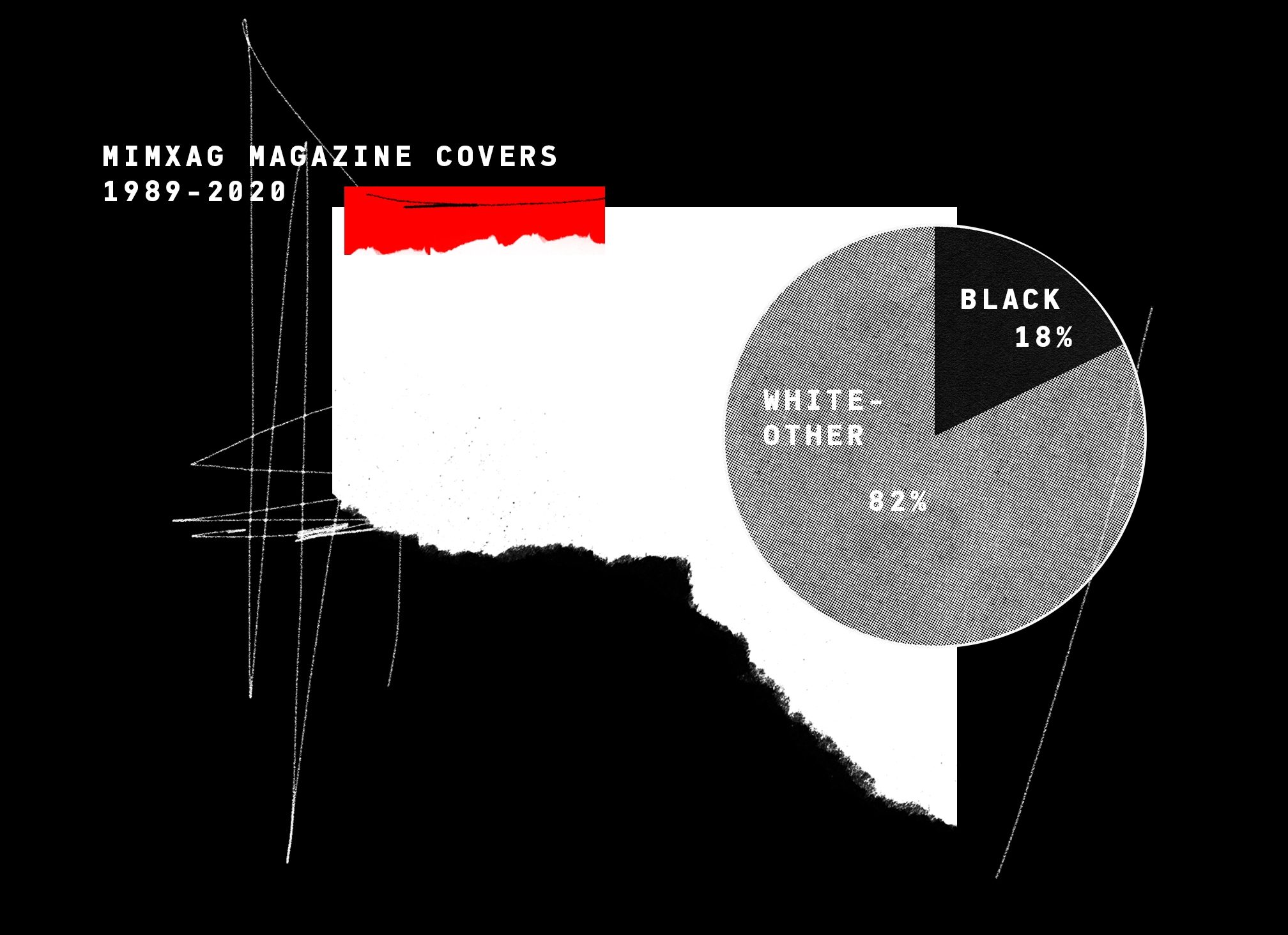

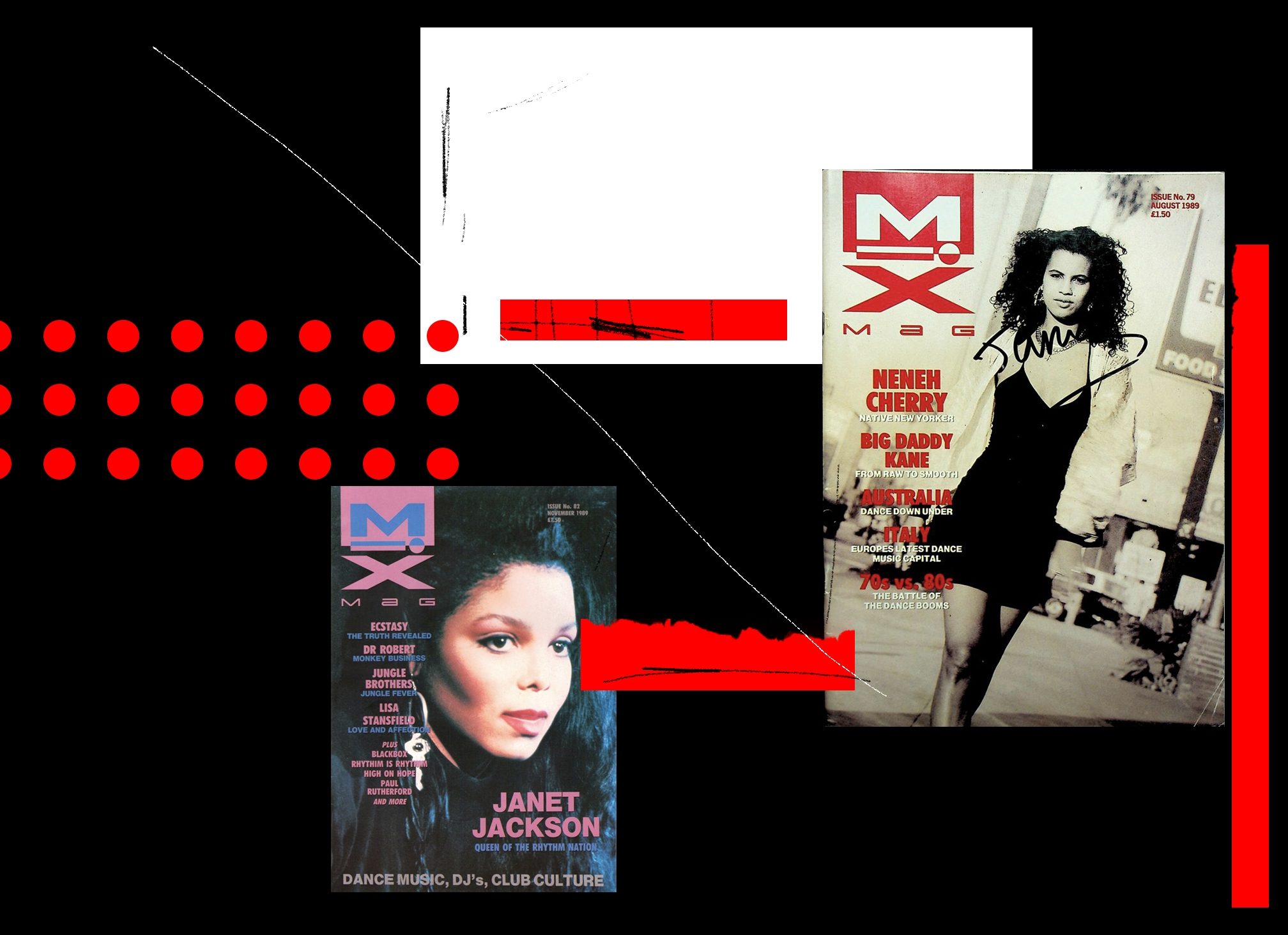

Mixmag launched in 1983 as a UK-only black and white zine featuring a cover photo of African American disco group Shalamar. Distributed by the Disco Mix Club mailing service, Mixmag circulated as a newsletter until establishing itself as the publishing company and the first dance music magazine in 1989. Throughout the 1980s Mixmag’s covers would consistently feature Black musicians such as Bobby Brown, Janet Jackson, James Brown among others as American pop culture began to filter into the United Kingdom. Before this, an event in 1979 called “Disco Demolition” or “the day disco died” was spurred by a Chicago radio show host and anti-disco campaigner named Steve Dahl who lead a riot of 50,000 white people who blew up disco, soul and funk records in the center of the Chicago White Sox's stadium in what could be called a white supremacist and homophobic act of terror on the American Black and queer dance community. Despite this, disco would take on a new life as a “progressive music” being pioneered by Chicago and Detroit's Black youth culture well into the 1980s after Motown records relocated from Detroit to Los Angeles in 1972––partially due to the race riots in Detroit in 1967. One could presume that at this time Mixmag the newsletter could not afford the rights to reproduce the images of American cultural exports like Prince and Michael Jackson, meanwhile white American consumers made a clear stance against dance music. But nonetheless, Mixmag covered Black music with a genuine interest until 1993. Though the September cover story of that year on the Prodigy asked, “Is this the final chapter for the rave scene’s last success story?”

A Black artist from Detroit wouldn’t grace the cover of Mixmag until Seth Troxler and Carl Craig in 2012; but the British, Afrika Bambaataa-inspired electronic act Leftfield would be featured in 1993. Leftfield’s album ‘Leftism’ pulled directly from Black music, but was ironically labeled “progressive house” by the magazine. The terms “leftfield” and “progressive house” would do two things to dance music: divide existing dance music genres into categories of dancefloor accessibility as well as placing a glass ceiling over the heads of the Belleville Three and future Black electronic producers. Mixmag making up a name like "progressive house” implied that the house music coming from the African American youth counterculture was not progressive despite “progressive music” existing in Detroit and Chicago from 1973 to 1985 while also displaying on multiple accounts a willingness to use Black music as an influence and basis without accreditation. Meanwhile, Artificial Intelligence, a compilation and series of releases of “electronic listening music” curated and distributed by Warp records between 1992-1994 would inform the “intelligent dance music” or “braindance” sub-genres and introduce artists like Aphex Twin, Autechre and Richie Hawtin. After frequenting and eventually throwing their own parties across the border in Detroit, Richie Hawtin and John Acquaviva, two white men from the Canadian town of Windsor, Ontario would start the label Plus 8 in 1994 with the debut release of F.U.S.E.’s 'Approach & Identify' containing a sticker that read: 'The Future Sound of Detroit'.

In a 1995 interview with Melody Maker, the late James Stinson of the seminal group Drexciya asserted that there was a “Caucasian Persuasion” over the history and industry of techno, “Ever since the blues and early jazz, Black music has been stolen and exploited.” The interview resurfaced in 2016, 20 years later, through a blog called Drexciya Research Lab that is dedicated to unearthing and organizing the myth and media produced by and around James Stinson and his collaborator Gerald Donald. Stinson's frustrations with where techno was going were quite clear in the article as he bluntly questioned “Why do Riche Hawtin and his Plus 8 family come down here and throw parties in downtown Detroit?” pointing out the influx of white suburban youth that began to gentrify the music scene while also affirming that techno was an original work developed by the Black community of Detroit as an expression of joyful resilience in the midst of urban decay and postcolonial melancholy:

“As far as I’m concerned, there isn’t anybody out there making original Detroit techno – apart from us, and that’s not being arrogant. It’s a plain and simple fact. A lot of people making so-called techno don’t understand where it came from and what it’s all about. I know this stuff; I’ve been doing it for a long time. I’ve been with the real deal, in the trenches, since this shit was born out of the womb. But so many people have come in and stepped over the name of original techno and toned it down. And that’s why we’re here: it’s time to turn up the heat.”

Mixmag would go on to document a narrative around drug addiction throughout European dance music culture with cover stories like “Why Does Speed Kill More People Than Ecstacy?” in August of 1996 and “Are Drugs Driving You Mad?” in February of 1997, peaking in 2018 with the sudden death of EDM superstar Avicii. Publicized drug usage could be considered a touchy subject for Black people, and is an example of what is meant when people talk about white privilege. Mixmag was allowed to publicly print stories about drugs and "drug safety" despite the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act of 1994, making raves in the UK illegal; while Black Americans were and continue to be overrepresented in arrests involving drug usage, and in the case of Breonna Taylor, killed by the police in a “War on Drugs” conducted by the United States government.

In 1999, two Editors of Mixmag’s first office in the US, Bill Brewster and Frank Broughton wrote a 600 page tome of a book called Last Night a DJ Saved My Life. Poised as a definitive history of DJing and dance music, the book at the very end of the 20th century collected the delirious decade-long hedonistic spiral of European rave culture into a single sober document. Brewster and Broughton, in the afterglow of the decadence of the 90s, detailed clubbing as a ground-level social revolution that was occurring in the UK in tandem with the expansion of American influence alongside the fall of Communism. In West Berlin in 1987, United States president Ronald Reagon declared in an infamous speech addressing the Soviet Union: “tear down this wall!" Those words led to the liberation of the Eastern bloc into a process of integration into a global free market economy and governing body allowing for a club culture to develop and thrive; meanwhile, urban areas in the United States with large Black populations like Detroit were left in financial ruin. The original preface for Last Night a DJ Saved My Life opens with the statement: “The story of dance music resides in the people who made it. Or at least played it.” Given the chart presented with this writing I’m prompted to ask who are “the people” whose stories are being told?

Business Techno Becomes an Industry Standard

At the turn of the century, the dotcom bubble burst and a lot of companies were beginning to lose revenue from a decline in overall industry profitability. The music industry began to reformat as the internet crept into the centerfold of our daily habits. At the same time, print magazines like Muzik and Jockey Slut were falling out of circulation. A subtext of both the late 90s and the economic strain felt in the industry today is that the demographic for dance music isn’t limitless and systematically gets older and eventually ages out. In the new millennium clubbers were entering their 30s, like millennials now, and began to slow down and focus on different priorities. So, the market low in dance music from 1997 to 2005 could be seen as transitional years to recoup relevance. Like many other industries, a series of bubbles and minor monopolies began to pop up using data and high speed internet connection as a basis. Following Last Night A DJ Saved My Life, Mixmag would take a turn away from American and British pop culture coverage towards the travel industry targeting a luxury leisure lifestyle demographic made up almost entirely of white and European male consumers. By 2017, Mixmag would rebrand as Wasted Talent Ltd, and purchase two other iconic UK magazines Kerrang! and the Face in a move to own and operate a fully integrated, cross-demographic platform.

In 2001, Discogs and Resident Advisor were both founded establishing a standard across dance music that catered to the refinancing of the industry with a somewhat elitist and technical mindset. If the 1990s were a time where Europeans discovered and experimented with techno as the basis of contemporary electronic music, then the 2000s was a full transformation into a hobbyist industry, producing the idea that if you have gear, software or even listen to music you should be making money off of it. To this end, Discogs operates as a kind of stock market, setting the global value of various physical music releases based on how readily available they are for purchase. Mirroring Pitchfork whose rating system for music reviews would make or break an independent musicians career in America, Resident Advisor sought to connect regional European clubs and scenes on a single platform, eventually opening a ticketing service and job board forming a kind of monopoly in the process (other club ticket providers include Ticketmaster and Skiddle). In 2002, the audio engineering website Gearslutz emerged as a community board for professionals and amateurs wanting to focus primarily on the technical expertise aspect of electronic music. In Denver, Colorado, online electronic music store Beatport was founded in 2004 as a place to catalogue and standardize dance music by genre and sellability –– notably receiving early investments and support from Richie Hawtin and John Acquaviva. In February of this year Beatport shared a press release, explaining its plan to expand the techno category on its website in close collaboration with over 200 majority white/European producers –– only four years after being put up for sale by SFX Entertainment, a live events conglomerate that was filing for bankruptcy having formed to capitalize on the EDM boom. Beatport’s founder and former CEO Jonas Tempel on May 25, 2016 penned an open letter at Magnetic Mag, describing how Beatport could be saved. Both Beatport and SFX Entertainment would recover and pivot focus away from dance music with new leadership.

Industry and consumer standardization put into place by competing independent operations is a feature of colonialism that at this point in history routinely extracts, adds and subtracts value as the market itself and the white men who gamble it needs. In a post-COVID music industry, we’re faced with a few problems: the decline of music sales in favor of wholesale streaming services and the inability to safely gather in-person for live events. The simple answer to this problem is for the industry to focus on selling units with publications covering music with an understanding that an album, EP or single are valuable in and of itself with an indisputable cultural context worthy of being explored through writing. White and European males have been and will continue to be the primary audience for dance music; but since globalizing their version of dance music culture and industry in a scramble to make money off of abstract data indicators like the number of “reads,” “plays,” and “views” a webpage could potentially get, their demographic began to encompass a more multicultural audience. Music publications operate as a kind of middleman in the larger distribution chain of the music industry, and its sole purpose is to distribute and sell music. Instead publications reformatted to run like tech startups just as investors began to realize that online advertising doesn’t necessarily yield profit. What we need now isn’t a projection of “progress” or “optimization;” we need to ground ourselves in reality and designate which platform(s) have the potential to sustainably distribute income and content evenly, keeping the assembling line of music releases and press coverage flowing and steady through our present crisis of demographic saturation and maturation.

Spotify CEO Daniel Ek in an interview with Music Ally, framed the streaming service’s supposed “audio-first” strategy, “not only are we talking about the music business, we’re going after all of radio, which is obviously a much bigger addressable market.” Ek continues, saying, “Some artists that used to do well in the past may not do well in this future landscape, where you can’t record music once every three to four years and think that’s going to be enough.” Since Sean Parker (who currently serves on Spotify’s board of directors) and Shawn Fanning leveled the recording industry’s financial structure by launching the peer-to-peer file sharing service Napster, there’s been a false claim being made by mostly white male analysts – who are neither workers nor even consumers of music – that online advertising and data-driven platforms like Spotify are helping the music industry make more money than it ever had. This is true only to the extent that Spotify is: a) ripping off every single artist and label using it, b) training consumers and businesses to rely on their algorithmic model, and c) Spotify is somehow different to other streaming services. That last point to me is the most important because we’re dealing with a situation that makes Spotify look like Pepsi and Bandcamp look like Coca-Cola while publications struggle to remain open and consumer attention strays to video-based streaming services and social media.

On August 18, Boiler Room announced a partnership with Apple Music, adding its archive to the streaming service, beginning an industry-wide process of consolidating assets to shift and maintain market value and consumer engagement. With the advent of online file sharing in the mid-2000s, DJs (and sometimes producers) began to purchase, illegally download, and play other people’s music royalty-free from platforms such as Beatport or Bleep. The free online mix has been a key component of music publications transformation into online platforms, and operates as a kind of free sample of music for consumers by an uncompensated tastemaker. Even beyond the scope of the Spotify algorithm, the DJ as a position in the music economy works a lot harder and more efficiently than platforms at practically no cost. When considering music publications as a kind of consumer menu or catalog, they suddenly start to look like they’re selling profiles of artists on a digital auction block more than neutral documentations of cultures and expressions. The scoring of albums; the naming of genres; and the presenting of artists, releases, and mixes to an audience forcibly determines the value of a personal, cultural product. This process is obviously extractive as there is no direct overhead from the publications or platforms besides the amount of initial money invested in the companies in the first place.

Electronic music websites made a point to only staff and focus on the tastes and interests of a single demographic for the majority of its existence; meanwhile, record sales had been in steady decline for the entirety of the 2000s. Now that COVID-19 has forced the industry to a halt along with the US increasing its fees and restrictions for artist visas, what we knew to be the dance music industry has been fractured and reduced to a re-evaluation of local scenes from financially failing music platforms. A remarkable difference between Europe and the United States is their philosophy towards the valuation of creative culture industries within a free market, commerce-oriented society. On June 4th, the German government distributed €1 billion for arts in a larger €130 billion pandemic stimulus. On October 6th, the UK Chancellor Rishi Sunak soberly stated that he, “can't pretend that everyone can do exactly the same job that they were doing at the beginning of this crisis.” Less than a week later the UK Arts Council awarded grants to bailout and “maintain England’s cultural ecology.” Controversially, Resident Advisor, a privately owned, for-profit media company and ticketing service, received £750,000 and Boiler Room received £791,652; meanwhile artists in the United States are still stretching the $1,200 pandemic stimulus distributed in March, and local clubs and venues either crowdfund or shutter.

In the end, despite pledges from magazines to finally diversify their content following the murder of George Floyd by police in the United States, truly independent and Black-run platforms such as Dweller and Black Bandcamp offer a glimpse into what could have been if the Eurocentric dance music industry was serious about properly integrating and sharing with their Black demographic. The 2010s subsequently ushered in a significant increase in Black artistic contributions and consumer base as a result of UK publication’s attempts to significantly grow their presence in the much larger and even less equitable American entertainment market. Though this platform and the attempt to make things right is appreciated, I implore the current and former staff and consumers of the dance music industry to actually sit with the fact that they on their own accord chose to actively colonize what they thought to be a thriving global market while also discriminating against its Black demographic from whom techno music was originated, allowing the proverbial ship to sink in the process.

DeForrest Brown, Jr. is a New York-based theorist, journalist, and curator. He produces digital audio and extended media as Speaker Music and is a representative of the Make Techno Black Again campaign. His work explores the links between Black experience in industrialized labor systems and Black innovation in electronic music. On Juneteenth of 2020, he released the album Black Nationalist Sonic Weaponry on Planet Mu, and Primary Information will publish his first book Assembling a Black Counter Culture in 2021

The Make Techno Black Again campaign has released a 2nd edition of MTBA hats alongside new limited-run T-shirts with design from A. Qadim Haqq and a new mix from DeForrest Brown, Jr