Cover stars

Cover stars

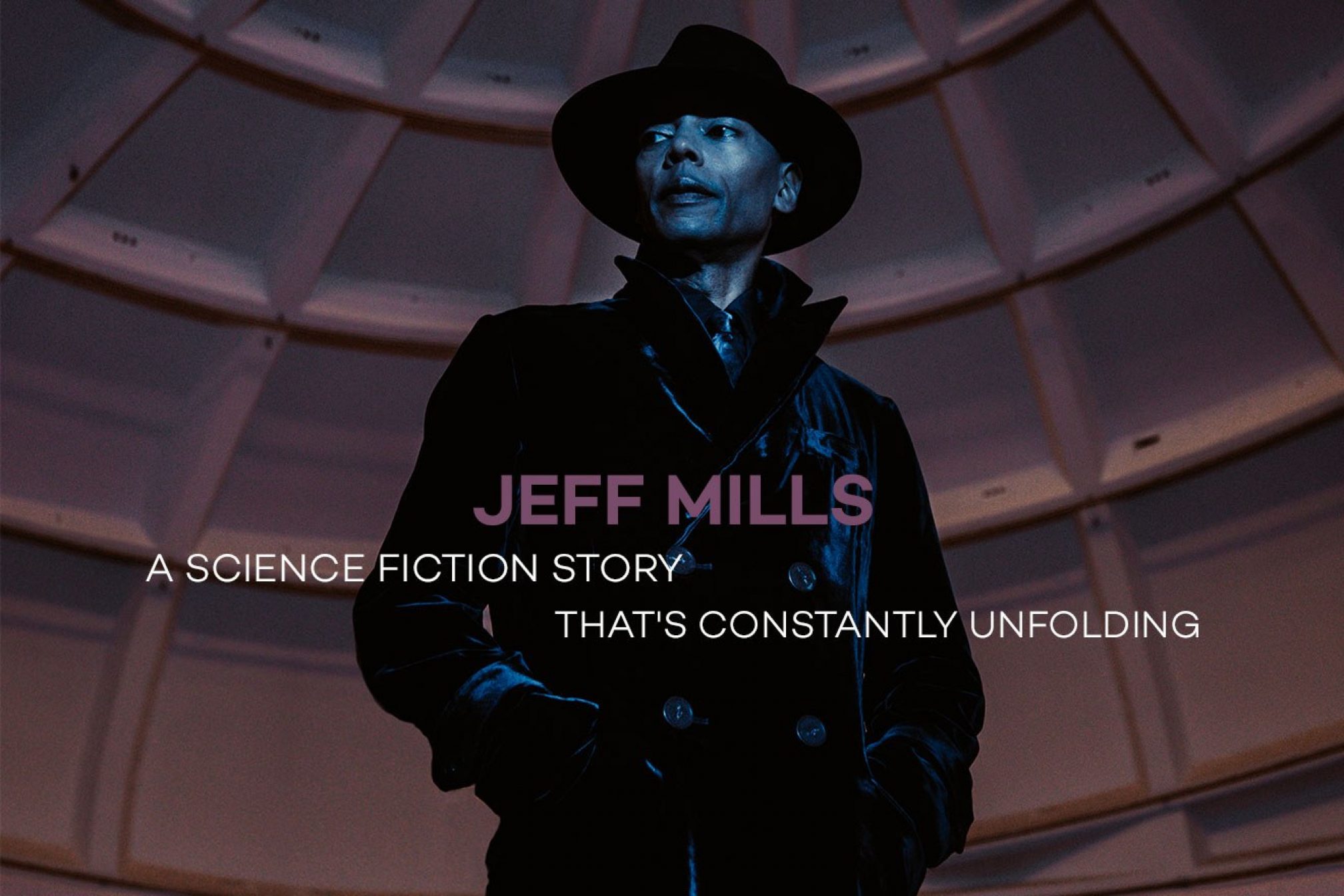

Jeff Mills: A science fiction story that’s constantly unfolding

Jeff Mills is more than a DJ, more than a producer, more than a musician

"The lines began to blur between reality and fiction around the mid-nineties.” Not an uncommon feeling for quite a few veteran ravers – but for Jeff Mills it means a lot more than just a hazy few years. Sitting in an extremely plush central London hotel bar, the morning after he casually annihilated the crowd at vast, gloriously dystopian rave cavern Printworks, the elfin, softly-spoken 55-year-old is telling Mixmag about the moment he tipped over from simply (simply!) being one of the most revered techno musicians and DJs in the world to something more. It was this point, somewhere around 1993–4, immersed not just in electronic music but in art, architecture, film, jazz, cosmology and above all science fiction, that he began expanding his Axis label, and the very fact of Being Jeff Mills, into a conceptual art project, a science fiction story that continues unfolding to this day. “I’d realised,” he explains, “that perhaps I’d gone too far and there was no turning back. I’d spent too many years – good years – on this path and I probably wouldn’t go back to school, and so I needed to maybe get a bit more serious about music and art.”

Mind you, it’s hard to imagine Mills not being serious about what he does. In person he’s unfailingly polite, and while full of enthusiasm there’s a nerdy nervousness to his mannerisms: he blinks often, he corrects himself constantly and will repeat a word over and over until he finds the right next phrase, and in contrast with the broad midwest drawl of Detroit contemporaries like Mad Mike Banks or Carl Craig, his clipped, soft enunciation sounds almost Canadian (Detroit is, after all, right on the border with Ontario). If you didn’t know he was a techno deity, you might take him, with the flecks of silver in his hair and his intense, inquisitive conversational style, to be a successful academic; or perhaps, given his subtly funky geometric print shirt, the jazz musician he might easily have been, having played drums since the age of seven.

Three things dominated his childhood: music, skateboarding and science fiction. He grew up the second youngest of six kids in a “very normal” area of Detroit, neither ghetto nor suburbs, and like most of the city almost all black – though his best friend was Chinese. Music was everywhere: “You just grew up in this atmosphere that was, like...The Supremes had lived over there, and Diana Ross went to this high school, and Marvin Gaye did this... everyone knew someone who played with Motown, or with the P-Funk thing. David Ruffin [of The Temptations]’s daughter Nedra sat in front of me in school. She was very tall; I had to keep leaning round her to see the teacher!” Mills’s drum teacher had played with Duke Ellington and he quickly became part of the school band, drumming at dances and functions, playing everything from Steely Dan to Kiss alongside current funk and pop – while his older brother was a sound engineer for a big jazz festival who would let him try out the desk and even operate lights for shows.

Skating he mainly did on the street – there were no pools or skateparks in 70s Detroit – but he got seriously good. Mills says skating taught him about overcoming fear, and also that, quoting pro skater Tony Alva, “You have to be good and look good doing it”. Sci fi and comics were also everywhere because, says Mills: “The Midwest was the hub for transporting everything [by train] and that includes pulp fiction, so we got everything! Detroit, Chicago, Cleveland, Ohio, Wisconsin all still have the biggest collectors... and the whole thing of space travel, dreaming of the future: that’s written into Detroit.”

But all that took a back seat when he discovered DJing. Detroit had a unique culture of privately organised formal dances for high school kids, and even when he was 12, Mills’s sister would take him along. “I learned about the dancefloor,” he says, “and what a DJ does, and how to socialise with people; how to pick up the girls, you know, which is a big deal when you’re twelve, right?”

The music at these parties was grown up, with the same DJs who’d play at adult clubs – and in Detroit that meant disco, deep funk, and especially tracks with spacey, electronic tones, which, as the 70s came to a close, increasingly included what they called ‘progressive’: European synth disco and synth pop like Cerrone,Telex, The Human League, and above all, Kraftwerk.

Then came hip hop and electro, and Mills found his calling with the new DJ techniques. But it was tough learning to cut and scratch with nobody to show you: “Back then communicating was difficult,” he says. “There was no video, so we would only hear through the grapevine what a DJ did, what Marley Marl did, what Red Alert did in New York. You had to reverse-engineer it, work out what they must be doing with the mixer.”

He learned fast. With a sense of style he credits to skateboarding, and speed and precision “from watching jazz drummers, fusion drummers – Billy Cobham, Neil Peart and Buddy Rich,” Mills fast built a reputation, and a name: The Wizard. As the eighties progressed, Juan Atkins and then Derrick May and Kevin Saunderson started creating a very particular Detroit take on electronic funk, and The Wizard was more than ready to represent it, cutting it together with rap, disco and ‘progressive’ in clubs and, from 1987, on the radio.

But while they were inventing the sound that became known as techno, his own first musical experiments were a bit darker. He often visited Chicago, where his sister had gone to live, and while he was picking up house music for his sets he’d also visit the notorious Wax Trax! label/shop, home of industrial artists like Ministry. Mills had became an industrial fanatic, into Throbbing Gristle and Skinny Puppy, “with a backpack and wearing all black, you know – big boots, the whole thing!” His first band, Final Cut (with Anthony Srock) was in this vein: very European-sounding and noisy. And he says, when he first met Mad Mike Banks, who at the time was in a funk band and making melodic house, “I convinced him to adapt to this style. That’s why Underground Resistance has this more militant style, because it came from my industrial roots.”

Right there, in that nexus between funk and industrial militancy, is where Underground Resistance found the magic formula, and – with one Robert Hood as their MC – begun to conquer the world. Though Jeff and Mike both still loved full-on, piano heavy, gospel-influenced house – as on their early work with Members Of The House and Yolanda – they quickly discovered that Europe was going apeshit for their tougher tracks.

Mills learned this the hard way on his first trip to Tresor in Berlin, where he’d packed Chicago house classics alongside Detroit records, but found that vocals cleared the floor. “How could you not like Chip E?” he recalls thinking, indignantly; “How could you not like Farley Jackmaster Funk, how could you not like Steve Hurley?” – and he vowed not to return. He was persuaded back, though, and this time he brought acid, Kraftwerk, and he and Banks’s harder experiments, and instantly became as beloved there as he was in Detroit.

In the heat of the rave explosion, things moved fast. UR kept a cascade of mind-blowing tunes coming through the early 90s – brutally hard, soulful and levitational, and all points in between – but Mills was having his eyes opened by the global travelling that DJing afforded him. In Japan, he felt as though real life and his sci-fi dreams were starting to merge; “in Tokyo, when it rained at night, it was so Blade Runner you would not believe!”. With each country he visited he started finding common factors and began dreaming of a “very universal kind of sound.” He moved to New York, recruited by the notorious Limelight club, who wanted someone who understood the European rave ethic, then Chicago, where he began to study architecture: “there were almost underground architectural bookshops in Chicago,” he laughs, “where you have to knock on the door to see the rare books!”

And it was here that his crux point came: the decision that his life wasn’t just going to be 12” after 12”, DJ gig after DJ gig, but would blur the line between reality and fiction, would become its own sci fi story. Increasingly, he left UR to Banks, who expanded the musical collective and kept the label intensely Detroit focused,a hub for community work and political activism. Mills already had Axis up and running and was spending a lot of time deep in conversation with Rob Hood, inspired by minimalist art and architecture, working on “stripping the music down to barely nothing... bringing it down to common factors so that we can all bring it back up together, in this very universal way.” This led directly to their H&M collaborations, to Hood’s still unsurpassable ‘Minimal Nation’, released on Axis, and to Mills’s run of absolute, brutal perfection on releases like ‘Cycle 30’, ‘Growth’ and ‘Purpose Maker’. By “experimenting with microform recording techniques, modifications to synthesisers, all kinds of things,” he created tones that sounded simultaneously ancient and futuristic, folding impossibly sophisticated timbres and patterns into tunes that slammed in the rave as hard as anything else on earth. With cryptic messages and artwork, and utilising the early possibilities of websites to link these hints into a bigger puzzle, Mills set about building every track and every action into one giant artwork.

Meanwhile, he was pushing his DJing skills up yet another notch. With the music stripped to minimalist essentials, his mixing got wilder, more maximalist, more improvised, with multiple decks and patterns fired off from a 909 drum machine. Anyone who’s seen him in full flow knows why it sent people into such frenzies: records flying on and off, spinbacks and tricks everywhere in a way that should be utter chaos yet somehow powers on with the groove. “Yes!” he enthuses. “It’s on the verge of chaos, round the edge of chaos. Which is on purpose. So I’m pushing, I’m pushing – I don’t know what’s going to happen next sometimes. Or I bring myself to a cliff, and I don’t know, I haven’t thought about what I’m going to play next, and I have to try and find a way to make it sound alright. And that’s done sometimes on purpose, because if I don’t know, then you certainly don’t know, and that’s what creates the drama and the suspense. Like, like – skateboarding,and not knowing if you’re going to make it, but you try, and you get better every time, [until], you know, you’re Tony Hawk... yeah!”

With these pieces all in place, Mills was set on a steady course, able to spread out into other spaces. The volume of work has been preposterous: not every part of it to everyone’s tastes, but he’s always questing, and always producing glittering clues to the bigger vision. In 2000 he wrote a score for Fritz Lang’s hugely influential 1927 sci-fi silent movie Metropolis, and since then he’s scored some 20 films. In 2006 he made the ‘Blue Potential’ album with the Montpelier Philharmonic Orchestra, far, far ahead of the current trend for orchestral dance music reworks. He always DJed – it runs like a pulse through his life – but some years he did it purely as routine, keeping himself distanced from the club industry. In particular, he says, he didn’t engage from 2006–10; he loathed the dominance of Berlin-centric minimal, which he calls elitist: “I’m not sure if it was conscious or unconscious, but it was creating this hierarchy in electronic music that I didn’t like, like it was us and them.” That period, he says, he spent listening to Miles and Coltrane, reading science and science fiction, and trying to create sonic codes that “are not necessarily speaking to the listener, or to the person, it was speaking to a higher presence. So, music that can speak to the stars.”

And that reimmersion in jazz has clearly paid dividends, because Mills has added live music to his repertoire again. There’s his ultra-slick and tight jazz fusion band Spiral Deluxe, a hark back to his days listening to Billy Cobham, Rush and Steely Dan. And then there’s his duo project with the Nigerian Afrobeat legend Tony Allen – in many people’s reckoning, even now at the age of 78, the greatest drummer in the world – for which Mills developed a whole new way of playing his 909: setting every drum playing every single note, then flicking the volume controls to play it, so he’s no longer locked to a sequencer grid but can truly jam, one drummer with another. “It’s afrofuturism,” he says; “you know, afrobeat, which is making me pay more attention to the works of like Sun Ra, and more cosmic type of work. And now I’m starting to think that, [for] electronic music, we don’t have an Arkestra [Sun Ra’s constantly mutating ensemble of avant garde musicians] – and why not?”

Both projects are ongoing, with gigs worldwide and quite remarkable records emerging. He’s on the verge of moving from soundtracking into film-making too – maybe not immediately, but “I think I pretty much have most of the resources, actors, access to actors, to film crew, to equipment, to certain locations, living in Paris as I do now... it’ll be science fiction, but in an abstract way.”

Crucially, on top of all that, and as Mixmag witnessed at Printworks, he can power through a techno set as well as anyone on earth, that mixing still making people double-take with shock and delight as familiar motifs appear and disappear, the music simultaneously so gloriously basic and startlingly advanced that you don’t know whether you’re coming or going, and it ceases to matter right there in the moment. And in that moment, you realise, you’re part of Jeff Mills’s art.

Yet he’s still looking to the future, still dreaming of being “able to walk into a club and not recognise anything around us, and the music should be so transcendant that it’s like a drug”, still believing that just as surrealism and dadaism and futurism emerged in response to the technology of the early 20th century, so something new is coming. “Technology will revolt, he says. “Maybe it will consume us, but I think by the mid 2030s we should be able to see the fruits of mixing things together, mixing people together, mixing ideas together. The hardware will shrink so much it will disappear, and we will be able to access it anywhere. The reasons why we listen to music will change, too. Most of us listen to music now because we want to be entertained, we want to feel comfortable, or it brings back memories. There probably will come a time when we may listen to music for other reasons, because that feeling makes us more healthy, or that feeling gives us information about something that we just didn’t already know.”

As he settles into this theme – the great theme of his art and his life – Mills seems to grow in stature, his hesitant repetitions gone, the sentences flowing as easily and with as much certainty as techno does from his hands. Aged 55, Jeff Mills continues to lead us into the future. We couldn’t ask for a better guide.

The ‘Director’s Cut’ series, recompiled and remastered classics by Jeff Mills (Axis/Purpose Maker) was launched on February 14. The second release will be out in April

Mixmag would like to thank the Faena Hotel and Forum, Miami

Joe Muggs is a freelance music journalist and regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter

Read this next!

Jeff Mills: Dark City soundtrack

The evolution of Jeff Mills

Floorplan: A spiritual encounter