Features

Features

The MOBO Awards need dance and electronic music categories

The last time the MOBOs recognised Black British dance and electronic music was in the early 2000s. Jaguar & Heléna Star ask why and call for these categories to be reinstated

UK Black culture’s most prestigious awards ceremony, the MOBO Awards (Music Of Black Origin) launched in 1996, becoming the first Black awards show in Europe. The likes of Sade, Public Enemy, Goldie, Roots Manuva, Lauryn Hill, Ms Dynamite and So Solid Crew have received the MOBO crown. After the 2017 ceremony, the organisation announced a 12-month break to reshape the ceremony for the following year. However, in 2019, the MOBOs were once again rescheduled, this time with no explanation, and so when they announced a show in 2020, anticipation was high. As soon as the nominations dropped, we rushed to the homepage and avidly scanned the long lists of primarily Black talent who would be in this year’s MOBOs hall of fame. Over the years, the MOBOs have awarded 300 trophies to over 1500 nominated artists and it’s become a platform of recognition and validation for Black art.

This year’s monumental shift in societal and social thinking, off the back of the Black Lives Matter movement during a global pandemic, adds even more weight to the MOBOs’ return. At a glance, it was positive to see the amount of Black women nominated. Black women’s stories have long been overlooked and overwritten in history, and so we were pleased to see esteemed artists like Lianne La Havas, Mahalia and Tiana Major9 with nominations. But after scanning through the categories, we noticed what was crucially missing. Where the hell is the ‘Electronic and Dance’ category? The hip hop, r’n’b/soul, grime, jazz, reggae and gospel lists look great, but who decided that ‘music of black origin’ stops there? Come to think of it, the omission of rock and alternative artists feels particularly chilling, as pointed out by rock duo Nova Twins in their open letter to the MOBOs, who cite rock ‘n’ roll’s Black female originator, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who influenced Little Richard, Chuck Berry and Elvis. They said: “rock ‘n’ roll is of Black origin, but because of systematic issues that we still face today our POC contributors to the genre have gotten lost along the way.” These ‘systematic issues’ are the result of genres growing in popularity and as white artists come in, the minorities are squeezed out. The MOBOs are an organisation at the crux of Black music, yet it seems odd to ignore massive parts of global history. After voicing our opinions about dance music’s inclusion in the MOBOs online, we were overwhelmed by the wave of people who got in touch and felt the same way.

Read this next: The gentrification of jungle

The last few months have given us strength to be vocal about electronic music’s Black origins, with Helena’s Techno Is Black range and Jaguar’s involvement in Mixmag’s Blackout Week. We both want to rewrite the narrative to acknowledge and respect electronic music’s Black origins, from our forefathers and foremothers in Chicago and Detroit, and of course here in Britain. It can feel like a constant battle to educate people about our white-washed and un-diverse line-ups and what this means for Black artists, so it has been positive to see many publications and organisations pledging to do better when it comes to supporting Black artists, and putting these plans into action. But it felt like salt in the wounds to see the MOBOs overlook a huge part of our Black heritage, and further add to the stigma that dance music is ‘white music’. Since when was music colour-coded? The amount of times we’ve had to stop ourselves from tearing at our afros in rage… If you have black or brown skin, people love to tell you what type of DJ they think you should be: they assume you play ‘afro’ house instead of house, or you automatically become a hip hop DJ, instead of a techno DJ. How are we meant to innovate and exist when we’re constantly suffocated by the weight of systemic racism? How can the next Larry Heard thrive when oppressed by damaging preconceptions? Being Black is highly nuanced and it should be treated as such in all communities. We spoke to SHERELLE who said: “I think people’s mis-representation and lack of education behind Black people within the dance scene, especially in the UK, is because people always think of jungle and garage in regards to our lineage, but they don’t necessarily think of dubstep or things going on as we speak now like house and techno.”

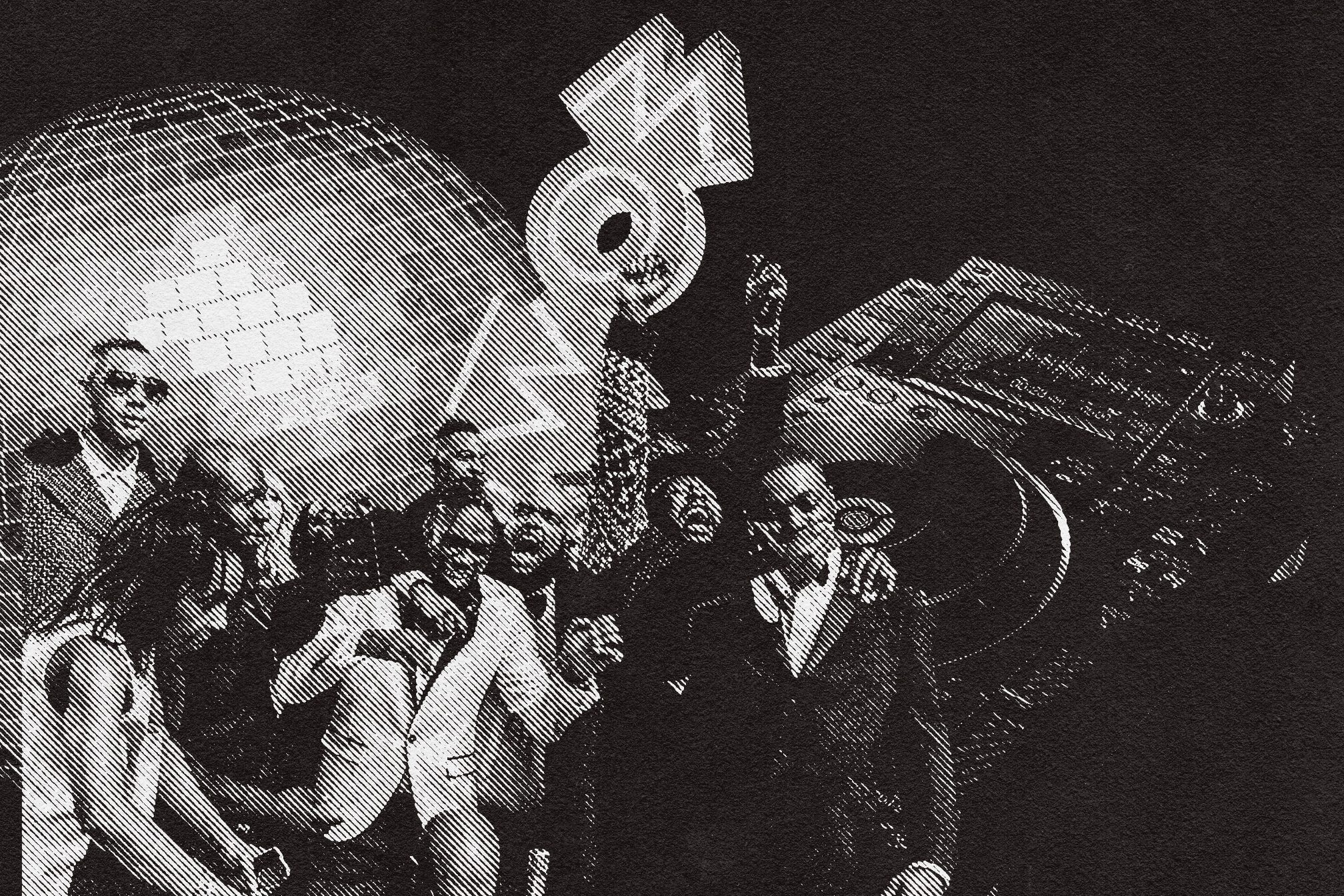

If we look at MOBOs history, in the first ever ceremony in ‘96 at London’s Connaught Rooms there were categories for Best Dance Act, which house group Baby D picked up, and Best Jungle Act, awarded to Goldie, who also scooped up Best Album. In his acceptance speech he talks about being proud to be British and it’s clear that this was a historic moment for Black electronic music. In the years that followed, Jamiroquai’s ‘Travelling Without Moving’ and Adam F’s ‘Colours’ picked up Best Album; Roni Size and Reprazent won Best Jungle and Shanks & Bigfoot and The Prodigy and won Best Dance Act. There was even a Best Garage category which So Solid Crew, DJ Luck and MC Neat and Lisa Maffia picked up. But by 2004, the electronic categories were gone and recognition of dance music had disintegrated. We spoke to two-time MOBO winner Goldie about the lack of electronic acknowledgement 24 years later, and he said: “Our own Black people denouncing Black music and Black dance music is the equivalent of the West rewriting King James’ version of The Bible! This is a regression and an insult to our own Black intelligence that you’ve decided to take away this category within your Misinformed Obligation to Black Origination”.

If we look at jungle’s history, as it grew mainstream, its underground, Black origins became gentrified, and white artists received recognition. Pioneering acts like Bryan Gee and DJ Flight were pushed out, as jungle ‘rebranded’ as drum ‘n’ bass, and the authority of Black people was lost. However, it’s positive to see the new wave of jungle and d’n’b artists like SHERELLE unapologetically reclaiming the sound, and paying homage to its Black beginnings. We need these figure-heads to shake up the narrative and give exposure to a Black history that has been exploited by white culture, as dance music has grown into the money-making industry that we see today. Therefore, white artists become headliners and superstars profiting off the culture created by Black pioneers who are ultimately left behind.

The problem stems from lack of education and accurate sources, resulting in Black erasure from electronic music. It runs deeper than an awards show. These damaging and false narratives suffocate Black culture, and what Black people are allowed to be. It’s our generation’s time to stand up and question what is out there for us, rather than what society expects.

Read this next: Kevin Saunderson "Black people don't even know that techno came from Black artists"

In 2020, the tired excuse from white promoters of a ‘lack’ of Black artists is unacceptable. We are here, we exist and Black music is not monolithic. We need more fluidity and unity between genres - by unifying, we have a better chance of reaching an equal world. The MOBOs have the opportunity to lead by example, and celebrate Black excellence and Black culture in all genres, instead of adding to the stereotypes of what is modern day Black music. This representation should be a priority.

We believe we can get there. The conversations sparked since Black Lives Matter have been electrifying and motivational – let’s keep them going. Allow space and initiatives to grow so we can rebuild our scene in the right way, and make dancefloors and line-ups truly representative of the diverse world that the industry was built on. The industry needs to earnestly act now by employing people of colour, to diversify its line-ups and champion emerging Black artists and artists of colour so they feel safe and supported, and treat the Black pioneers with the same reverence we treat our white heritage acts. Now is the time to address this and is instrumental to the growth, understanding and acceptance that dance music is Black music.

Mixmag has reached out to the MOBO Awards for comment

Jaguar is a broadcaster, journalist and DJ and regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow her on Twitter here

Heléna Star is a producer, DJ and broadcaster. Follow her on Twitter here

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs