Culture

Culture

Northern Soul and the birth of the all-nighter

Northern Soul all-nighters helped set the blueprint for raving as we know it today

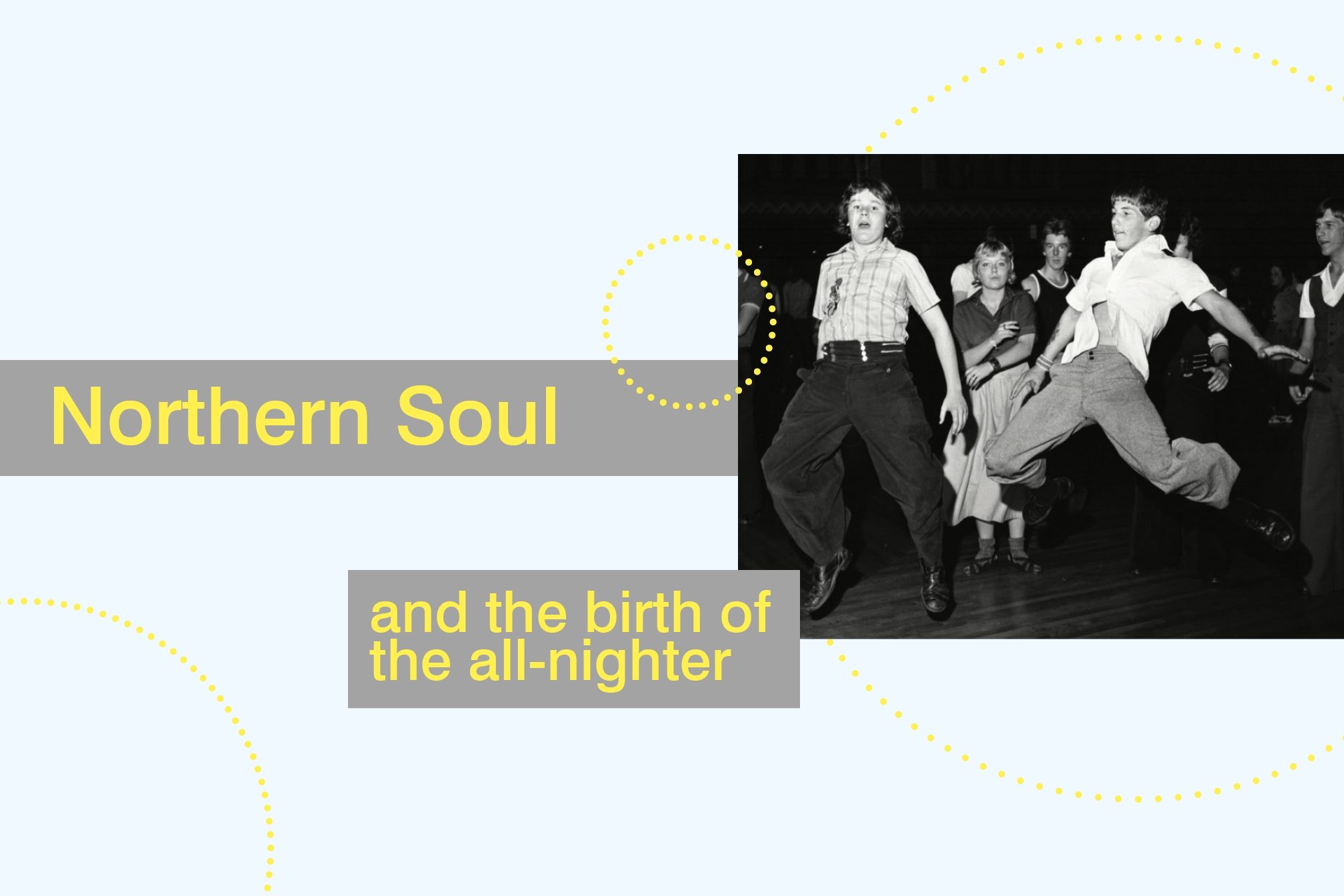

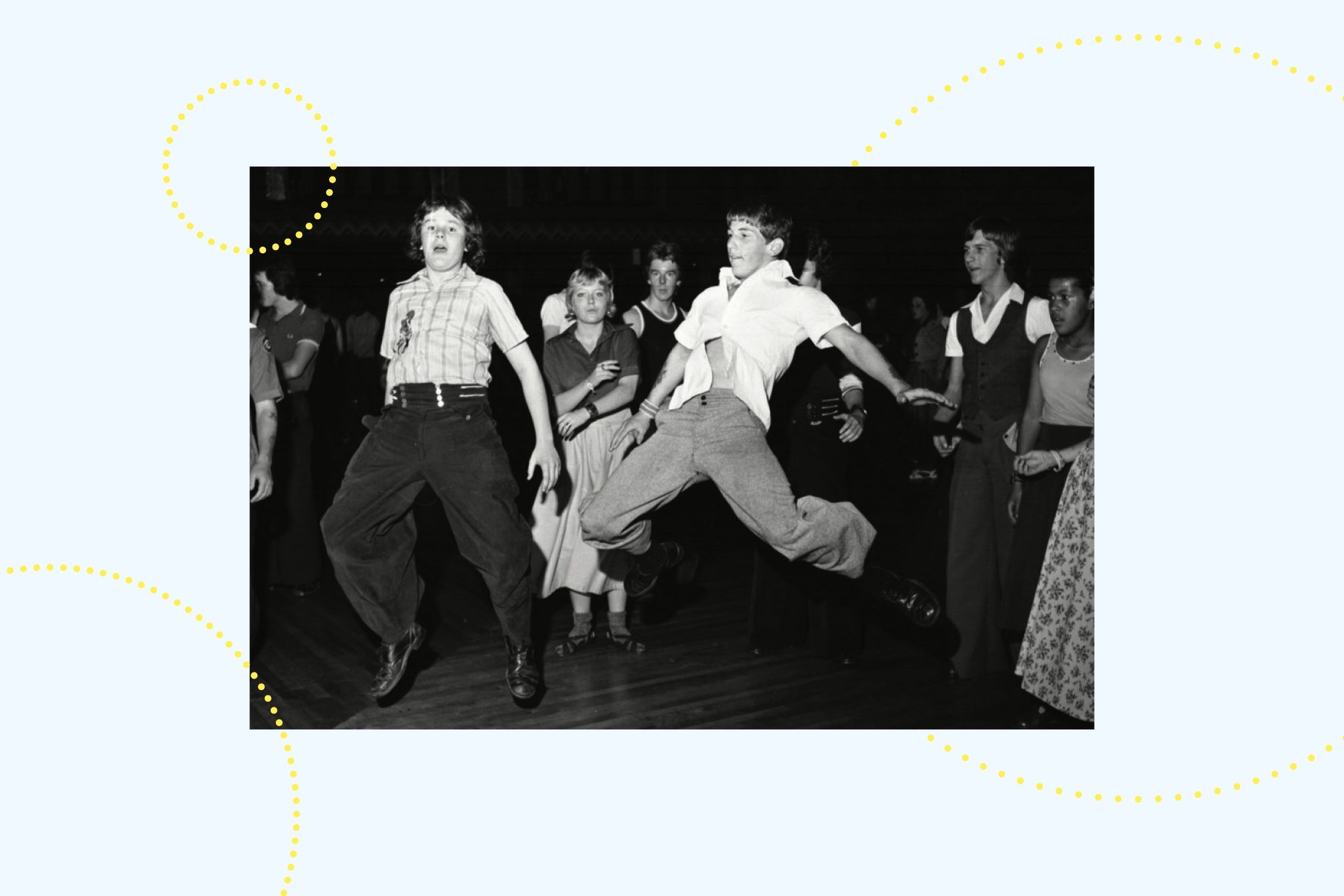

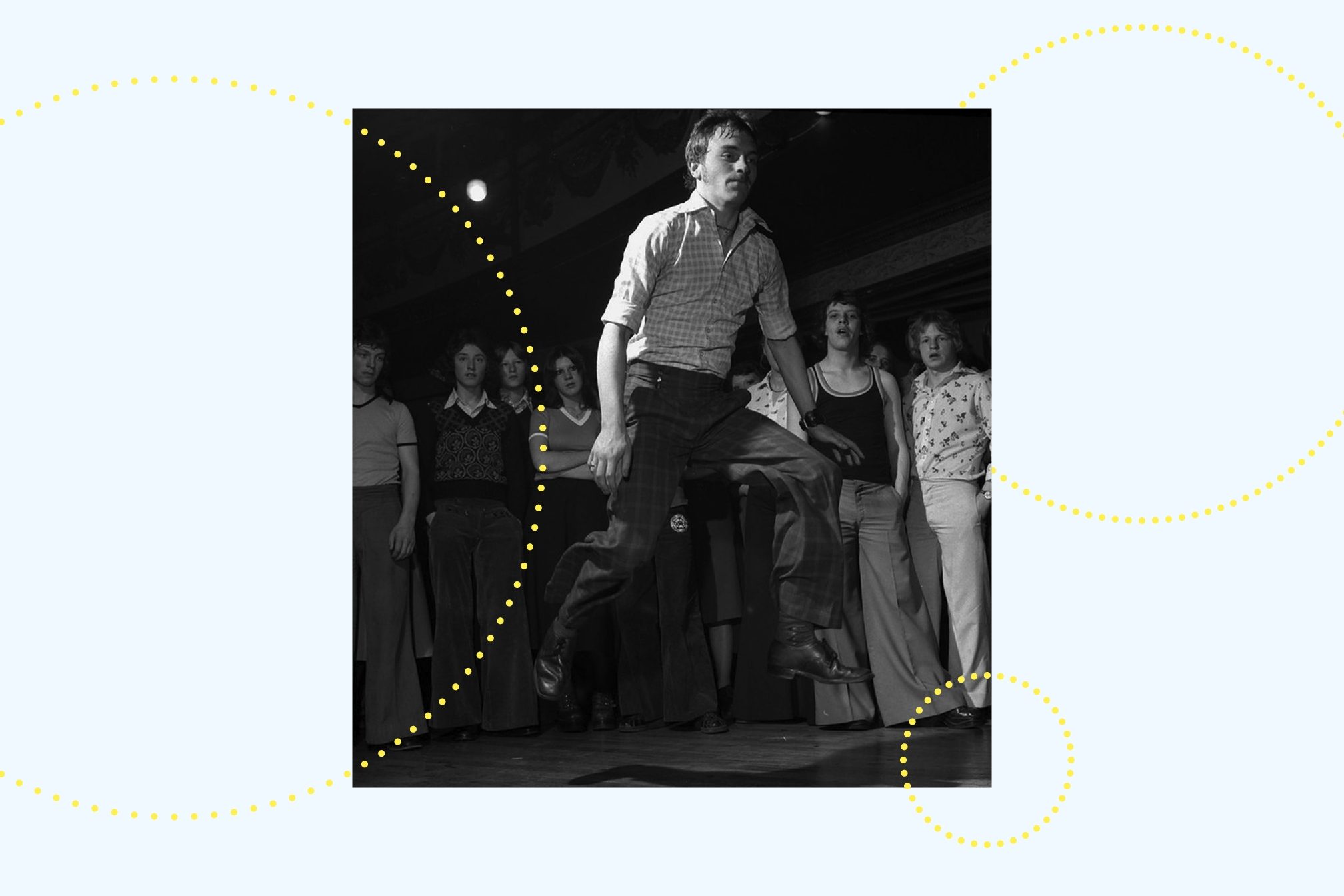

In the 1960s, young people in the north of England partied like they never had done before. Industrial towns like Wigan and Stoke were injected with a new energy when imported soul music began to soundtrack their ballrooms, function halls and working men’s clubs. These spaces, and the working class youths who filled them, gave rise to the Northern Soul scene and its famous all-nighters where dancers – in wide-legged trousers, vest tops and clutching bowling bags stuffed with talcum powder (to keep dancefloors smooth, of course) and speed – would move in a blur of sweaty limbs in time to US soul rarities until dawn.

These events, held in venues such as Wigan Casino, Talk Of The North in Cleethorpes, Stoke-On-Trent’s The Torch, the Twisted Wheel in Manchester, Catacombs in Wolverhampton and Blackpool Mecca, were powered by kids dancing furiously and helped create the all-nighter as we know it today. That is, the format of going out and not coming home until the next day. The Mods, another British subculture founded in the 60s that idolised American r’n’b, rode scooters and dressed in sharp slim-fit suits, were among some of the original nightclubbers, dancing late into the night and taking amphetamine to aid this hedonistic activity. But the geographical split between the Mods in the north and south of England led to northern Mods creating their own rare soul scene and how they partied all night long pioneered how we rave today.

Read this next: High Contrast Northern Soul set

“I suppose you had to go to your working class,” says DJ and lifelong Northern Soul fan Keb Darge. “The people who wanted your more honest life, didn’t like hippie music and thought ‘fuck this shite’, and so wanted to hear this soul stuff.” He’s talking about how the rare soul scene was born through a geographical divide and, as people like Darge would argue, better music. In towns and cities such as Cleethorpes, Stoke, Blackpool, and areas that weren’t historically known for their nightlife, working class kids and DJs found space to create the kind of club culture they wanted to inhibit from scratch. Venues were easily accessible and not what you might call commercial establishments, as they were situated in parts of town that weren’t central enough to bother anyone who wasn’t already in the know.

The working class nature of the scene informed its aesthetic, giving freedom of expression through music and dancing to the disciples of Northern Soul, away from the grind of the 9-to-5. It’s often suggested that factory life and menial jobs allowed for the scene to blossom as, quite simply, people needed the release at the end of a long week.

However, the class status of the scene wasn’t the only thing that defined it, and it has been said that this angle was exploited for commercial purposes. The TV documentary This England produced by Granada at the time explicitly linked the factory industry with all-nighters, using images of molten copper being poured with the title ‘Wigan Casino’ at the forefront.

Read this next: The clubs of Northern Soul

“Well for most of us, we arrived that night and there was great big lights booming in your face, and there was a north/south divide much bigger then,” Keb remembers. “So I’d do a bit of dancing then someone else would do a bit of dancing and all you’d hear is [mimicking posh accent] ‘Oh lovely, fabulous, could you do that again? We’d like to get that on camera.’ Immediately I was like ‘Fuck off you cunt.””

Manchester’s The Twisted Wheel, which opened in 1963 and started out as a Mod club, is now cited as the first Northern Soul venue to hold all-nighters. The club started out by playing British pressings of rhythm ‘n’ blues, which soon evolved. It was the first club to play what would go on to be known as Northern Soul, a term coined by journalist David Goding in 1970.

At the time Godin had a record shop in London and grouped together all the similar sounding records that Northern football punters would look for when down in London following northern teams. He titled the box ‘Northern Soul’, something that London customers weren’t interested in. Wigan Casino DJ Richard Searling said: “I used to avidly follow the recommendations of Dave Godin in his fortnightly articles in the Blues And Soul magazine.”

DJs like Ian Levine would often venture further to the States to buy demos and rare records that had never really seen their day when first released in the US. It gave a DJ gravitas to play a new discovery at a club, which is why DJs would always be on the hunt for the next biggest soul tune, digging deep into US warehouse archives. Other DJs leading this charge were Richard Searling and Colin Curtis.

Read this next: Pretty Green Northern Soul collection

“I got sent to Philadelphia three times in 1973 to bring back in-demand 45s which enabled me to build a collection that got me asked to DJ at the Va Va’s all-nighters in Bolton,” Searling says. “At the start, my biggest ‘discovery’ would have to be ‘Tainted Love’ by Gloria Jones or ‘Easy Baby’ by The Adventurers.” Richard also agrees with Keb that a lot of the scene’s DJs’ collections and discoveries came from dealers like John Anderson, dubbed the undisputed number one record dealer of the era.

“The scene turned vinyl record collecting into an obsession, some of the scene's 'holy-grail' records change hands for thousands of pounds,” explains journalist and record collector Stuart Cosgrove. “The most famous records associated with the scene, Frank Wilson's 'Do I Love You (Indeed I Do)' on the Motown subsidiary Soul Records, changed hands at auction for over £25,000. But that is very much the tip of an iceberg.”

The rareness of a discovery, along with the reaction of the dancers, is what helped you build a name for yourself as a DJ. And dancing is what filled these venues each week from the early 1960s. “Right hand side. Down the front,” remembers Keb. “Dance contests began on the scene as far back as The Twisted Wheel in 1967. You soon knew the dancer’s names - Booper from Widnes, Matchy from Rotherham, Gethro for Wolverhampton, Caesar from Leeds,” says Cosgrove. “By the 1970s many of the very best dancers were also martial arts champions like Keb who represented Scotland in martial arts.”

Northern Soul all-nighters set the rave blueprint as they would often not get going until 2am and would be open until 8am. Amphetamines became the drug of choice as it increased hyperactivity and interest in repetitive activities, aka dancing your ass off. A lot of the early soul clubs didn’t have a licence to sell alcohol so using amphetamine would aid all-night dancing. Durophet, a mix of amphetamine and dexamphetamine, made by Riker Laboratories was also popular, so much so that some dancers started wearing T-shirts stating ‘I’m a Riker Liker’ as a nod to their underground scene.

Predictably, an underground scene of drug-taking teenagers dancing to black American music wasn’t going to go under the radar of the authorities for long. The Twisted Wheel was unfortunately situated opposite a police station and the moral panic surrounding the club led to its closure in 1971. The Torch in Stoke-on-Trent, a club that had opened in 1964 but only hosted its first all-nighter in 1972 in the reaction to The Twisted Wheel’s closure, also had its fair share of troubles. The club hit a 1300 people capacity during its peak, however came under fire in 1973 from Stoke-on-Trent council, when the council refused to renew its licence for drug-taking and overcrowding. The area of Wigan soon being dubbed the Heart of Soul due to the imprint the Casino made as the pinnacle of Northern Soul all-nighters was shut down in 1981 due to more policing and council issues. Police had been irked by the venue for years, and the council revoked its licence as they wanted to use the venue for redevelopment plans, which subsequently never happened.

In 2019, the most prevalent northern soul nights can be found in London’s 100 Club and Rugby’s Allniter at The Benn Hall among other nights around the north. These nights tend to roll through until 6am, meaning patrons of the scene can travel from across the country and catch the first train home; even this part of the night boils down to tradition. Now Northern Soul nights are more about keeping the subculture’s tradition alive, rather than revolutionising the dancefloor. So although the all-nighter as we know it began decades ago, what’s at the heart of it really hasn’t changed: A community of people brought together by their love of music.

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs