Scene reports

Scene reports

Nyege Nyege is a genuine, experimental African utopia at the source of the Nile

Uganda is the home of Nyege Nyege, a festival with progressive programming

On a sticky Sunday afternoon, the source of the River Nile is a riot of afro-punk fashion and twerking. A rapper in a velour pink top, Sho Madjozi, is commanding the crowd in Swahili and swinging her braids around to a pop take on gqom. The crowd – mostly from Africa and impeccably dressed – erupts every time she shouts her song’s turbo-hype chorus of “Wakanda forever”. It’s fitting: Uganda’s Nyege Nyege festival feels like a genuine African utopia that’s about to go global.

The festival is the ebullient binding agent for the disparate threads of electronic music that are spreading across East Africa, from traditional sounds tucked away in remote villages that have been revived by cheap software (such as electro acholi) to genre-shredding beats concocted in bedroom studios by young producers. Nyege Nyege’s Kampala-based founders Derek Debru and Arlen Dilsizian have been releasing sounds like these to acclaim on their label for the past two years. Their main event is now in its fourth year and has expanded to 9,000 capacity, with sponsorship from a local mobile network provider.

Even with the backing of a sponsor, however, it’s not easy to put on an event of this scale and quality in a country with very little resources or established festival infrastructure. Equipment is scarce here, and Dilsizian says that there are “only two CDJs available for rent in the whole country”, costing $400 per day. As a result, at the festival they are constantly having to move them from one stage to another, timing it so that artists are able to play. The Nairobi-based DJ Suraj Mandavia, meanwhile, has undertaken a nine-hour drive to get a Funktion-One soundsystem from Kenya to the festival site, a derelict hotel and grounds in southern Uganda.

There are also conservative ideologies to contend with, levelled by a generation for whom the inclusivity of rave culture is an alien concept. Two days before the festival, Uganda’s Minister of Ethics issued a buffonish statement calling for Nyege Nyege’s cancellation, saying that it was encouraging “deviant sexual behaviour” such as homosexuality and even – much to some performers’ amusement – bestiality. “The only animals here are party animals,” says one of the hearteningly vast number of female DJs on the bill, Kampala’s self-styled ‘trap princess’ Hibotep.

The festival goes ahead after some negotiation with the government, with its progressive programming intact. And that line-up – as with the people in attendance, who are largely Ugandan, Kenyan, Tanzanian, Rwandan, South African and workers from NGOs – is astonishingly diverse compared to other electronic gatherings. It brings together vernacular music from the region with European experimentalism and a plethora of contemporary African DJs, including a notable number of young guys from Dar Es Salaam’s thriving singeli scene, a gabber-speed electronic sound that’s booming among Tanzanian youth, as well as a burgeoning South African gqom contingent.

“There’s just so much electronic music here it’s mind-boggling,” says Darlyne Komukama, a DJ and photographer involved in running the festival. She’s hosting the Eternal Disco stage where many of the boldest and most envelope-pushing DJs are performing: New York’s Juliana Huxtable, Dutch DJ Marcelle – who plays the sound of someone screaming part-way through her set – and hyped Kenyan DJ Slikback. The festival is a shop window, says Komukana, for African music’s potential, beyond western producers using the odd ‘tribal’ drum in a track. “Instead of making music with samples [taken from] the internet, why not come here and make it with people who are from here?” she says.

Those sentiments are echoed by Dilsizian, a Greek-Armenian anthropologist who’s lived in Kampala for nearly 10 years. “There’s a Western stereotype of what African music is,” he says; specifically, “an exaggerated amount of attention on the ‘golden era’ of African music” that’s currently being played by selector DJs. Then there’s the WOMAD image of African music, he says – like the palatable style of bands like Ladysmith Black Mambazo. But Arlen says there is a third, untapped area of traditional African music that’s more abstract but is in “direct conversation with a lot of modernist strains of contemporary experimental electronic music.”

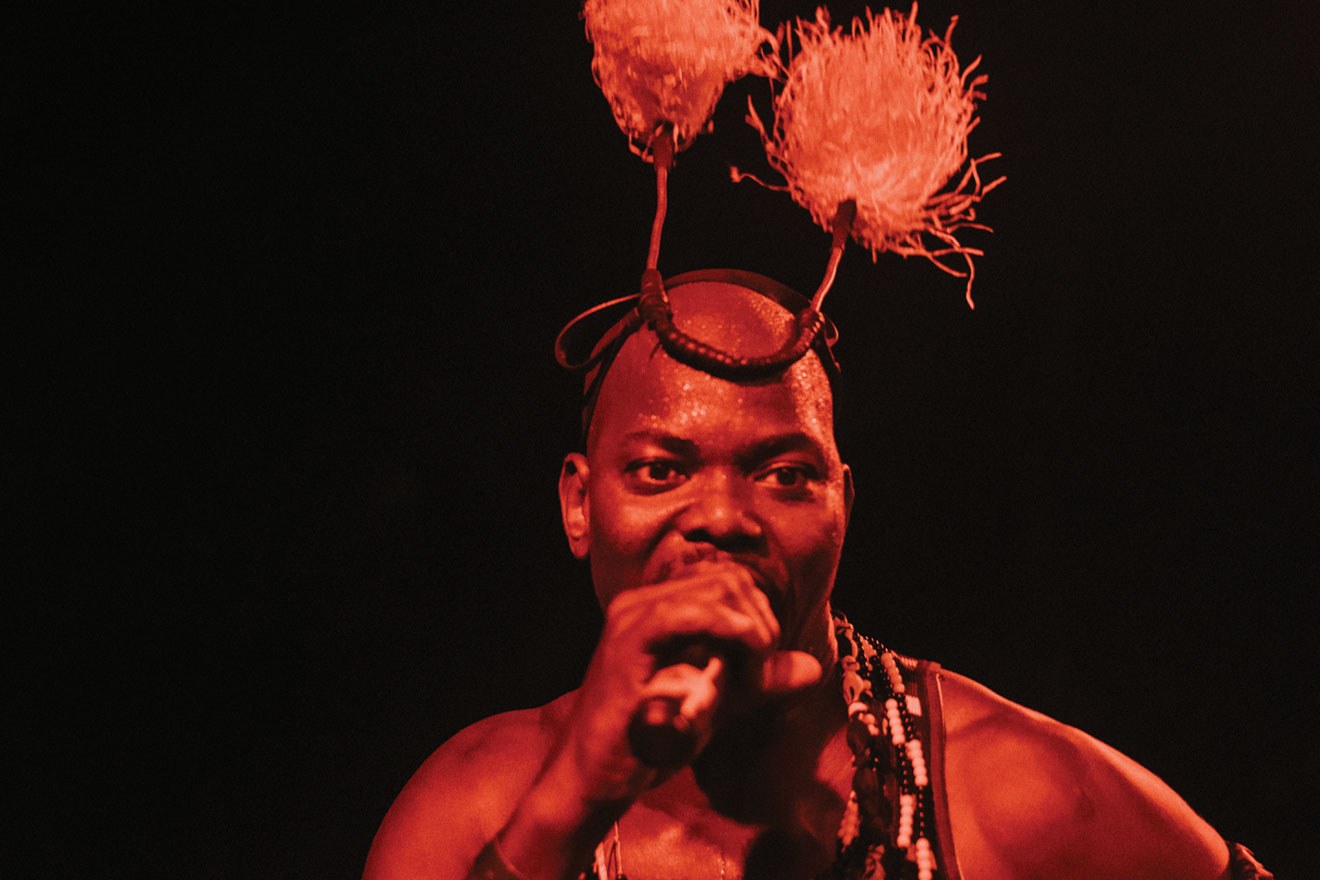

One of those more abstract forms comes via Nilotika Cultural Ensemble, who open the festival on Thursday with hypnotic drumming from the Buganda region paired with synths. Then there’s Otim Alpha, a rotund gentleman from the northern area of Gulu who at one point leads a procession through the throng with his troupe of dancers and percussionists. They perform acholi party routines in the crowd, flickering hip movements making their feather headpieces jiggle and living up to Nyege Nyege’s name, which is Lugandan for “the uncontrollable urge to dance”.

For those musicians who make music outside the mainstream, there is little opportunity to get on radio or TV in Uganda and the surrounding countries, where dancehall and afrobeat are dominant. So Nyege Nyege provides a much-needed platform and networking opportunity for home-grown talent.

We bump into MC Yallah, a Ugandan-Kenyan MC who has recently released an EP on Nyege Nyege’s digital imprint Hakuna Kulala who agrees that the festival has “given us the exposure and opportunity to meet a lot of people.”

Perhaps because of this network, there’s been a fair bit of talk in the media recently of an “East African wave” of electronic artists. It’s true that there is a patchwork of producers who are making contemporary music in line with SoundCloud and club trends, and that many of them are keen to rehabilitate traditional and distinctly East African styles – such as, in Kenya, benga – with computerised ones. In Kenya there is a new middle-class movement dubbed ‘Nu Nairobi’, for example, centred around the capital’s arts/club space The Alchemist, where production collectives like EA Wave make soulful electronica in the style of Bonobo and Kaytranada. But this is a far cry from a sound like singeli, which is bubbling more organically out of the ghetto.

Kampire, a breakout DJ who has been touring Europe this summer, agrees that it’s hard to pin down the East African underground’s sound. “One of the cool things about East African music, but also the difficulty in marketing it,” she tells us on the dancefloor, “is that the region is so diverse. It’s impossible to pin down one sound, like ‘South African house’ or ‘West African afrobeats’.” But, she adds, “for those who have lived here all our lives there are certainly sounds that are distinctly East African, such as the adungu [an eight-string bowed harp] and soukous guitars [a Congolese style, with vocals in the Lingala language].

But then you have young EA producers like Slickback who is Kenyan but is comparable to any of the producers who could be here from around the world.”

Dilsizian says that there’s a “greater demand” for more forward-thinking DJs from East Africa such as Slikback right now – “and that’s happened extremely fast.” Other names to watch, who make the kind of avant-garde brutalism you’d hear on a label like PAN, include Kenya’s DJ Raph, Disco Vumbi and KMRU, as well as Uganda’s Faizal Mostrixx and Authentically Plastic.

But as much as the Nyege Nyege festival provides a platform for these producers, there’s a sense that the label is subtly shaping their direction, too. Back in Kampala, we catch co-founder Dilsizian at Nyege Nyege HQ, a large villa and live-in studio where artists can stay and work for free. Various singeli producers are sat on mattresses on the floor tapping at their laptops; Slikback and his cousin are on a bunk bed. “The label and festival has had a proactive role,” Dilsizian explains, “bringing club music that’s happening in the West into conversation with what’s happening here. We’ve been giving young producers like Slikback, for example, dumps of Amnesia Scanner and this kind of music. They choose what excites them [from that selection]”, he explains, pointing out that it means that “they’re getting inspiration from further afield.”

That idea works both ways. In the future, Nyege Nyege may well be talked about in the same breath as Dekmantel or Unsound as one of the best places in the world to spot the next frontier in electronic music. Surveying the array of people and moves on display as the main stage comes to a close and a traditional performer sets his head alight and somersaults over another, it feels like the future of festivals: excitingly diverse, consistently surprising and committed to uncontrollable dancing.

Kate Hutchinson is a freelance journalist, follow her on Twitter