Features

Features

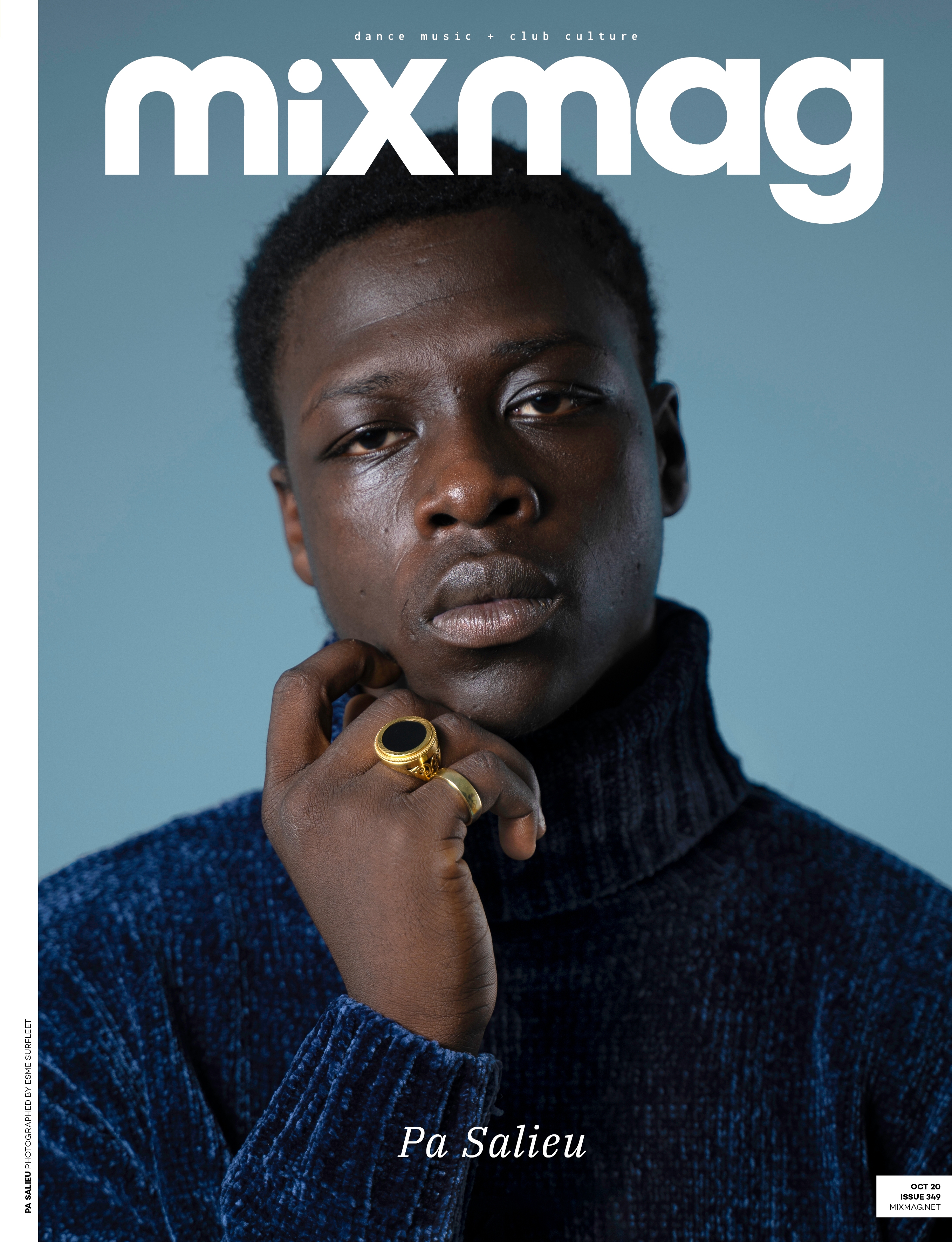

From the dust: The rise of Pa Salieu

Aniefiok ‘Neef’ Ekpoudom meets Pa Salieu, the Coventry MC on the frontline of UK rap

Pa Salieu is on the cover of Mixmag issue 349 – read his cover feature below

The family named 23-year-old Pa Salieu after his late uncle, his father’s eldest brother who was a police officer in Gambia and was killed in a motorbike accident while on duty. The eldest Pa was a beacon for the family, a man who “everyone looked up to” and provided for his siblings.

“I’m the oldest in family too,” Pa tells me, “I’m trying to finish off the feeling he started.”

We sit in a darkened room in a wing of his management’s sprawling West London offices. His silver rings glint in the late afternoon gloom as he reclines on a sofa that stretches the length of the room. The past few days have been shoots and interviews, press and music videos as the 23-year-old rapper from Coventry prepares to release his debut project ‘Send Them Back to Coventry’.

It signals the closing of the first chapter of a life that has strayed the lines and stretched the continents, flitting between the West Midlands and West Africa, the legal and the illegal, the miseries of life out on the roads and the dazzling rewards of a new career in UK rap.

“I might speak about all this crud and that” he says, “but that’s what I’m coming from. I want authenticity to stay in me. Music is guidance, it’s how you take it.”

Born in Slough, Pa was sent to live with his grandparents in The Gambia, a small country on the coast of West Africa. Those early years back home carry gold-plated childhood memories. In Gambia he says, “I used to be with my grandma, grandma’s boy.”

He remembers the trips to the quiet villages where donkeys pulled karts through the roads. In the back of their house, his grandfather kept a farm where chickens roamed the compound, and mango and apple trees grew from the dust. Elsewhere, the family had a mosque built in the front room where the local community would gather to worship. On most days, when the afternoon set in, neighbours would arrive to eat, the extended families sharing food on big ceramic plates.

The experiences in his motherland have moulded him he says, “the whole vibe, the whole spirit, the whole family” flames the deep pride he takes in his roots and the blazing urge to give back to where he comes from. The Gambia is in his blood and always on his tongue. The country moves through him, remains close to his spirit, is the subtle accent that animates the words that fall from his lips as he half raps, half croons over drum-heavy, rowdy instrumentals.

“Something is calling me back home boy”, he says, “I ain’t coming from the dirt, I’m coming from the dust.”

Away from his mother for almost a decade, Pa would have visions of her visiting. Then at age 10, his parents called for him to be sent back to Britain, and before long he was on a flight over the Atlantic, slightly unnerved about his fear of heights, sailing into a new life in a country he hadn’t seen since he was a one-year-old.

Britain was different than he remembered. It was concrete tower blocks in Coventry. It was snow. It was a new primary school where the kids taunted him about his accent until a parent pulled his mother aside and whispered that the environment was not safe, that “you need to get your son out of here.”

By secondary school he was being excluded for fighting, lashing out at those who tried him.

“I’d rather have pride in my culture,” he says. “Pride kills brothers, pride can fuck you up. But pride in the right situations, in your culture and who you are is like a balance, you know!”

The family had settled in Hillfields, a suburb north of the city centre. It’s a place that has welcomed immigrants in waves, a place once known for its booming manufacturing industry and the Highfield Road stadium home to Coventry City football club. But in recent decades, industry has waned, the stadium has been demolished, the football team has moved on and Hillfields is now one of the region’s most deprived areas.

It’s a bleakness that he hints at in his music. “I come from a side of town where you either eat, or be eaten, in the Hillfield strip,” he raps on ‘Year Of The Real’ alongside Manchester rapper Meekz and South London’s Teeway. “The ghetto is what made me old,” he continues in the verse. The lyrics are a candid glimpse at a bleak time in his life. After his grandparents had passed, Pa took to the streets to get by. “I put my time in the trap,” he says in that same verse, and on 2019’s ‘Dem A Lie’ he says, “We only did it 'cause of circumstance.”

Today he remembers “area shifts” and “bandos,” and how “It was hard to get away from it.”

“It was circumstance,” he says, “But nobody wanted to live that. I had to do what I had to do to survive. Even if it was gonna fuck my shit up, I’d rather have survived than…”

In his spare time he would find relief by recording spoken word freestyles on his phone and uploading them to Instagram to an audience of the two or three people. “It was a stress release ting,” he says, “someone told me ‘carry on doing what you’re doing, it’s going to make you feel good.’”

But as the years passed, the real dangers of the roads began to bare their teeth for the young kids like Pa who had been raised in the cracks. In the streets he remembers distress, boys who had their skins pierced by needles and blades, “people getting shot up, left and right,” the close friends exhausted by traumas, slowly losing a grip on their mental health and eventually bound to the sealed walls of mental institutions.

Elsewhere, in the fallout there are friends of his in prison who “got fourteen years, seven years,” he says, friends in jail, “that had to do what they needed to do, or that same moment it would have been them - circumstance.”

Some days friends would find him on the strip and drive him to a studio in Stoke-on-Trent, introducing him to his first producers. When out in Staffordshire, he would spend two days “building,” recording music and crafting lyrics before heading home to Coventry, back to Hillfields, back to the strip.

The music surfaced on the internet in drips – two videos on GRM Daily in 2018, a few freestyles thereafter as the early stems of a music career began to take shape.

In 2018, his friend AP was killed and music turned from hobby to a serious career. Before his passing AP had started his own clothing line and pushed Pa to take a serious turn at rapping. AP saw something in their futures Pa says, “but it got caught short. So what he sees I have to see and actually do it. I see it and I’m going to make it reality. It’s all not for nothing You really do live through people, you’re living through your ancestors, you’re living through so much.”

In February 2019, Pa released a freestyle with UK rap platform Mixtape Madness. Gliding over a mellow instrumental he raps, “I had a dream that I’m dead up / head-top red up / must’ve got blown by a two barrel [shotgun] / how did I end up and slip like this?”

Eight months after its release, outside a pub in Coventry’s city centre, Pa was shot in the head with the same gun he had dreamt of in the freestyle. Twenty pellets pierced his skin. Fighting to keep his eyes open, he staggered down the stairs and called an ambulance, guided by a quiet voice in his head with a defiance in its tone, telling him “Fuck that. This has just started. Ain’t nothing gonna stop me, no way.”

Pa woke up in intensive care with 16 pellets buried beneath his skin. Two days after surgery he was discharged from hospital and was back in the studio soon after. The shooting moved something in him, seems to have deepened his faith and his connection with spirituality. There is a steel and intense focus when he speaks now, his conversation always circling back to his mission to build back in Gambia and to inspire the others like him, who also came from the dust.

“I don’t see nothing left and right,” he says, “I’m just following. It’s like I’m being pulled innit. I don’t sleep, I just want to go to the next day man and see what’s there, see why he has kept me alive.”

A few months after came ‘Frontline’, Pa’s debut single official, a frank yet anthemic glare at the darkened corners of Hillfields. “Graveyard shifts of the day and night, just my food that these fiends wan take,” he raps over wailing sirens and a set of gloomy synth and drums that throb and moan like wildcat howls piercing a haunted midnight.

In the year that has followed, his life has changed in the major and the minor. The release of ‘Frontline’ catapulted him from Coventry to the frontline of British rap. ‘Frontline’ and then ‘My Family’ with Backroad Gee have both been released to wide acclaim. There have been campaigns with Burberry and dazzling magazine covers. On a trip to Kent he saw the countryside and stared out at Britain’s sea. “I know it ain’t nothing,” he says, but “I would’ve never got to see that.”

Elsewhere, he has been working on debut project ‘Send Them To Coventry’, set for release on November 13. Latest single ‘B***K’ is a rumbling reflection on his personal pride and wider Western society’s troubling attitudes towards Black skin.

As the first chapter of his life draws to a close and a new era opens, there is the sense that Pa is not shedding his skin but instead carries the flashpoints of his life with him, that the chaos of Coventry, the shotgun pellets, the studios out in Staffordshire and the golden memories of Gambia are to never be forgotten. They are the quiet reminders and the subtle inspirations as he rumbles on, eyes set on his mission.

Aniefiok ‘Neef’ Ekpoudom is a freelance journalist, follow him on Twitter