Artists

Artists

"Maximum energy": How Paranoid London became the most riotous act in dance music

Paranoid London break their no-interviews rule to talk clearing dancefloors in Ibiza, giving two fingers to minimal – and the joys of banging acid house

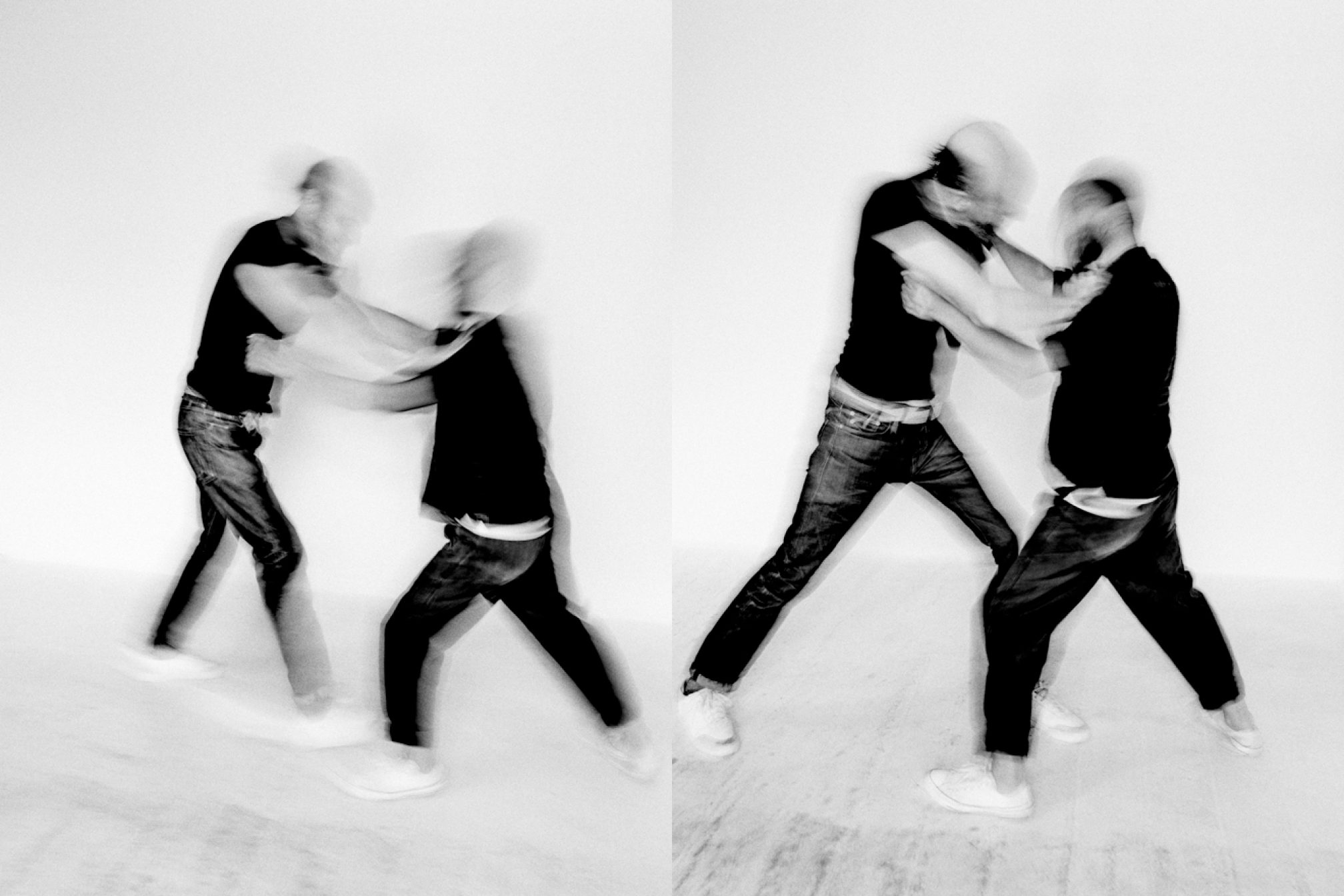

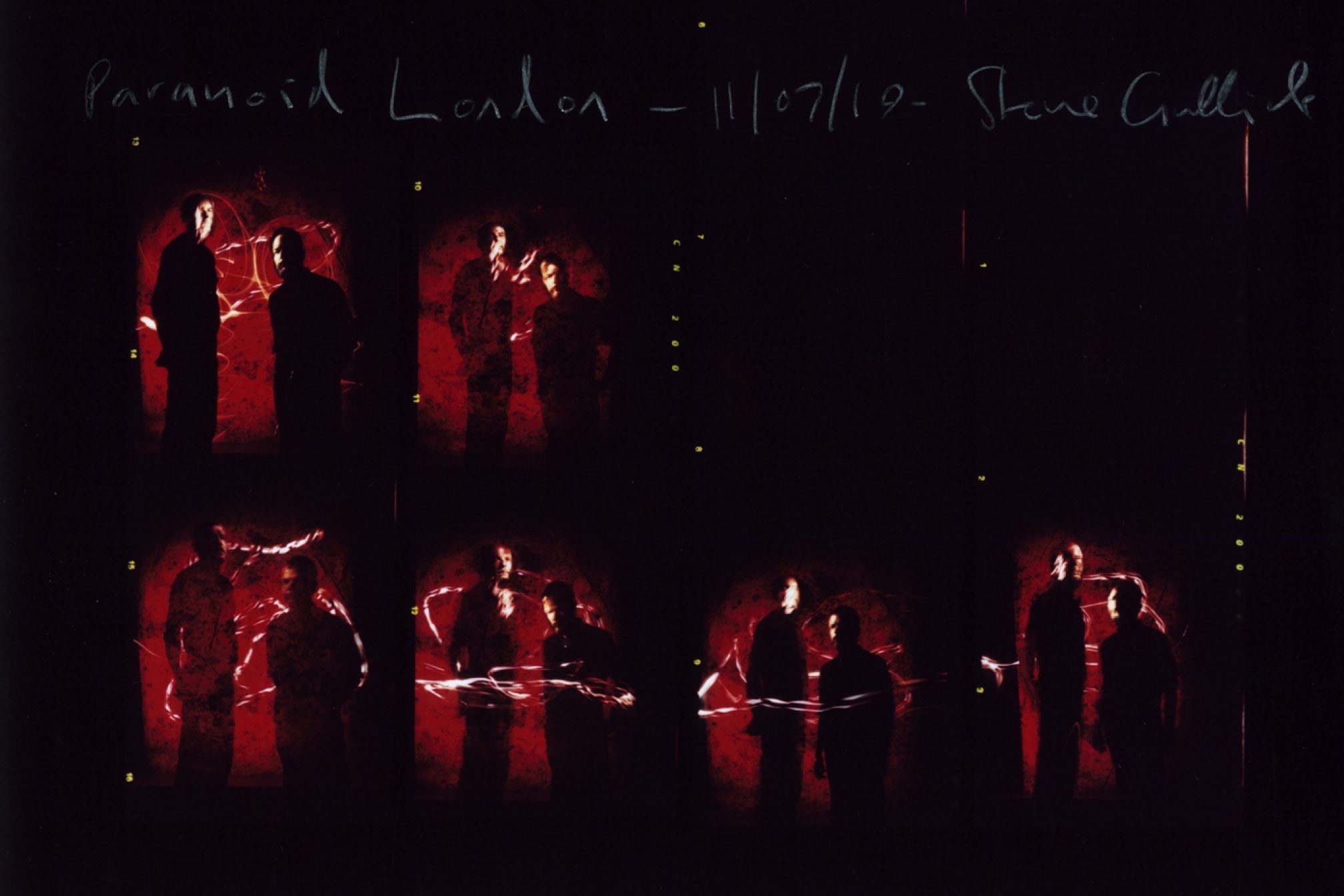

Paranoid London are playing their first gig at Paris’ Rex Club, late 2014. Out front a semi riot is going on, and staff are threatening to shut the show down. Having been swinging his mic wildly around his head, singer Mutado Pintado, aka Clams Baker, has disappeared into the crowd, replaced on the mic by a random girl who’s making orgasm noises. Quinn Whalley, one half of the group’s founding duo, has followed Clams out of view trying to rescue him, leaving a bemused Del, aka Gerardo Delgado, tweaking their heavily distorted 303. When the group finish and haul their gear out of the venue, the kids in front of them part in reverence, still awestruck by the chaos they’ve just witnessed. That’s the Paranoid London effect.

Since the first, single-sided white label on their own Paranoid London Records in 2007, Del and Quinn have been bringing an anarchic old-school approach to making music and playing gigs, putting freakiness and fun first and foremost with their raw, strictly hardware acid sound. They’ve taken rowdy live shows to the world’s most prestigious clubs and events, from Panorama Bar to fabric, ruffling more than a few feathers along the way. Initially shrouded in anonymity and only pressing limited vinyl, for their second album, ‘PL’ (out now), they’re finally breaking their interview silence for the first time – for Mixmag, naturally.

We meet in a Dalston pub down the road from the studio housing the set-up that’s made their records: an 808, 303, 909, 101 and Korg MS20. With swept-back hair and neat beard, 48-year-old Del still has the sartorial edge and single-minded attitude of someone whose first inspiration was Junior Boy’s Own, his musical education taking him from shopping in Soho’s Trax Records to working in Fat Cat, via trips to New York’s Vinyl Mania to buy hard-to-find disco and post-punk gems. Constantly rolling cigarettes and bubbling over into cackling laughter, 47-year-old Quinn has a wiry energy that before PL powered him through various scenes as a DJ, producer and engineer, from early days as part of Slack on Andy Weatherall’s Sabres Of Paradise to near chart success in the noughties while half of Different Gear.

We pick up the story 15 years ago, when Del was introduced to Quinn after losing his previous studio engineer.

When did your relationship click in the studio?

DEL: “Initially I’d get a load of records, come in and say ‘I’m really into this’. We spent years chasing other people’s sounds, which wasn’t working. I won’t release music until I’m really happy with it.”

QUINN: “He was coming to the studio and paying me to make music with him, then never releasing it. So I asked, ‘What are you really into?’ ‘Banging acid house.’ ‘Funnily enough, that’s what I’m really into!’ We thought, that’s what we’ll do.”

What happened next?

DEL: “Instead of moving blocks around, we decided to buy all the equipment back and make it live again. That’s when it started to become fun. It was expensive, especially when you bought your first 303 about thirty years ago for £30 then had to spend two grand buying another one!”

QUINN: “With a couple of machines we could both go nuts. For years, neither of us knew how to program a 303, so we’d just sit there and stab out random patterns. We’d go through thirty until one of them sounded good, then record it for ten minutes, chop out the boring bits and that was the track.

“The beauty was that we’d finish tracks in two or three hours. Then we had a conversation one night: ‘Let’s start a really arsey record label!’ It was a time when everyone could get anything on the internet.”

What was the ethos? Was there a grand plan?

QUINN: “We remembered the excitement of being kids. When you went to a club and they wouldn’t let you in, it made you want to go there even more. Or you’d be in a record shop and you’d find the record you wanted, then Danny Rampling would be standing next to you and they’d take it off you and give it to him. We thought, if [only] we could get that kind of thing going! So we’d always press fewer records than there were orders for.”

DEL: “Because the records were only sold in record shops and there were no promos, it was getting the DJs off their arses to go buy them. If not, a bunch of kids would have them and they wouldn’t. Start working again mate.”

How about the name?

QUINN: “It’s from the day of the 7/7 bombings. We went to Phonica on what seemed a lovely day, came out and the whole of London was on lockdown. It was really weird. We had to walk to the studio, which was in Old Street. It was Del who came up with it.”

DEL: “I also like having the word ‘London’. Everyone goes on about Berlin and New York, but nobody mentions London. We’re not from London, but we work here and we’re proud of it. If you live in Berlin and every ten minutes you have to say London it winds you up, which is part of what Paranoid London is about.”

Who or what inspired the PL sound?

QUINN: “It was never smiley-faced English rave kids in a field, it was gay, black Chicago, mid- to late-80s stuff.”

DEL: “As kids we were more interested in the records between the anthems. The DJ would play four tracks and you wouldn’t know what they were: growling, no intro or breakdown, didn’t do anything for five minutes, but damn good. I also never liked records that were slick. Those sounds that nobody wants, that’s what I want all over our records. I just want to hear hiss. Quinn absolutely got it; it was a partnership made in heaven.”

QUINN: “When we’d send stuff off to be mastered we’d have to tell them, ‘Don’t clean it up, please’. It’s still like that when we play live. Nine times out of ten the in-house engineer will ask, ‘Are you sure it’s meant to be that distorted?’ Oh yeah!”

You had the legendary Paris Brightledge sing on ‘Immortality’ in 2008, when you were still producing as One Last Riot before changing your name in line with the label. How did that happen?

QUINN: “Mark [Potts, one of the group’s managers alongside Alex Knight, co-founder of FatCat Records] knew him and suggested we did a record, but we knew we had to do something twisted...”

EDL: “... so we did a cover version of The Fall. Let’s give someone who can sing [a track from] the band who are the worst at singing in the world and make it an acid house record. The easiest option would have been to get him to do a big anthem, but it’s not about that.”

QUINN: “He did that on the next one.”

Was 2012’s ‘Paris Dub 1’ your breakthrough?

QUINN: “‘Eating Glue’ was good, but we only ever pressed five hundred.”

DEL: “I was living in Ireland for about six months and Mark phoned me up to tell me ‘Paris Dub’ was going off. ‘Shut up you donut’. ‘No, it’s going off!’ People were charting it and making a bit of a fuss. OK, I thought, we might have something on our hands.

“Making a record with the biggest bassline of the year and Paris Brightledge singing soulfully was also two fingers up to the minimal sound. Minimal was great in the beginning, it sounded like Detroit – but by the end there was nothing to it.”

How did the live show start?

QUINN: “Krysko, who is good mates with Mark, suggested we play The Warehouse Project [in 2008]. We had to write the whole set the night before. We only had three records then, but were playing over an hour. [We thought], If we pull this off, it’s going to be brilliant. We did, and it was.

“When we started doing live shows proper about five years ago, we looked at Boiler Room, that kind of stuff, and a lot of it was boring. So we got our mate Clams, who does the Mutado stuff, and he sent it off into the stratosphere. Nobody had seen anything like him. He’s one of those people who attracts interesting situations.”

How did you meet?

QUINN “He was a club promoter in New York, so I used to play for him. He’s been fronting bands for years and years. It’s rare you get someone that good.”

DEL: “He also set our benchmark for vocalists. Anyone who sings for Paranoid has to be like Paris: either they can actually sing, or be a damn freak. We have the soulful side and the freak side.

“You invite people, like Josh Caffé [who features on the new album], into Paranoid thinking it’s going to steady the ship, but it just goes off. Another lunatic we need to look after!”

What do you recall of the early shows?

QUINN: “From the off it was always chaotic. Maximum energy.”

DEL: “I remember all the local DJs would come down to see who it was. They’d hide behind the speakers. We’ve been about quite a bit, so a load of people know us. When they did actually find out who we were, it was always ‘Really? You two?’ – which was great. We sold acid house back to them! It was like reinventing the wheel, but really only pumping up the tyre a little bit.”

What’s changed since then?

DEL: “We’re still trying to make riots, but now the bouncers have cottoned onto us.”

QUINN: “As much as we can, we try to have Josh and Clams, who we call Grandma and Auntie B, together. They egg each other on, constantly getting people up on the microphone. We’re getting some weird visuals together too, not the usual kind of thing.”

Are they any times you haven’t gone down well?

QUINN: “We got booked in Ibiza. When we got to the club it was a millionaire’s playground, people were pulling up in their yachts, stepping out in white linen suits and espadrilles. We were supposed to do three gigs over the summer. We knew it wasn’t going to go well. We literally cleared the place. They emailed our agent on Monday and said ‘Here’s the money for the other two gigs, please don’t send them back’.”

DEL: “That was good fun. We’re quite lucky that normally we get booked by people who know what they’re getting.”

The sadly departed Alan Vega from Suicide, and Simon Topping from A Certain Ratio are on the album. Is the post-punk spirit as important to you as acid house?

QUINN: “Alan Vega is the best there’s ever been, for me. Weirdly, me and Clams went to see him at The Barbican, then the next morning, out of the blue, there was an email from Arthur Baker saying he had this track he’d made with [Alan] and never released, would we remix it. It was mental. Arthur released it digitally and didn’t really do much with it so we got in touch and asked to put it on the album. Bless him, he said yeah, so next thing we had Alan Vega and Arthur Baker on our album!”

DEL: “When I was growing up, A Certain Ratio were the nearest thing I could see that was the same as me. They were a bunch of white kids from Manchester making very bad funk, but it worked, and they were signed to Factory – everything I wanted. To me, punk and acid house are the same thing. It’s do it yourself, and you don’t have to be very good. As long as you can get the groove, and as long as you can blag it that you’re better than everyone else, you’ve got a chance of making it. We’re going to try to get him to do some of the live shows.”

Why did you decide to do your first interview now?

QUINN: “Boredom. We wanted to do it differently for the second album – the exact opposite of what we did for the first one.”

DEL: “It’s going to piss a lot of people off: ‘I can’t believe they’ve sold out and are talking about it!’ We don’t care, mate.”

Paranoid London’s new album ‘PL’ is now on Paranoid London Records

Read this next!

The Keyboard Wizards Of Acid House

The history of acid house in 100 tracks

14 DJs tell us their favourite acid house record

Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs