Features

Features

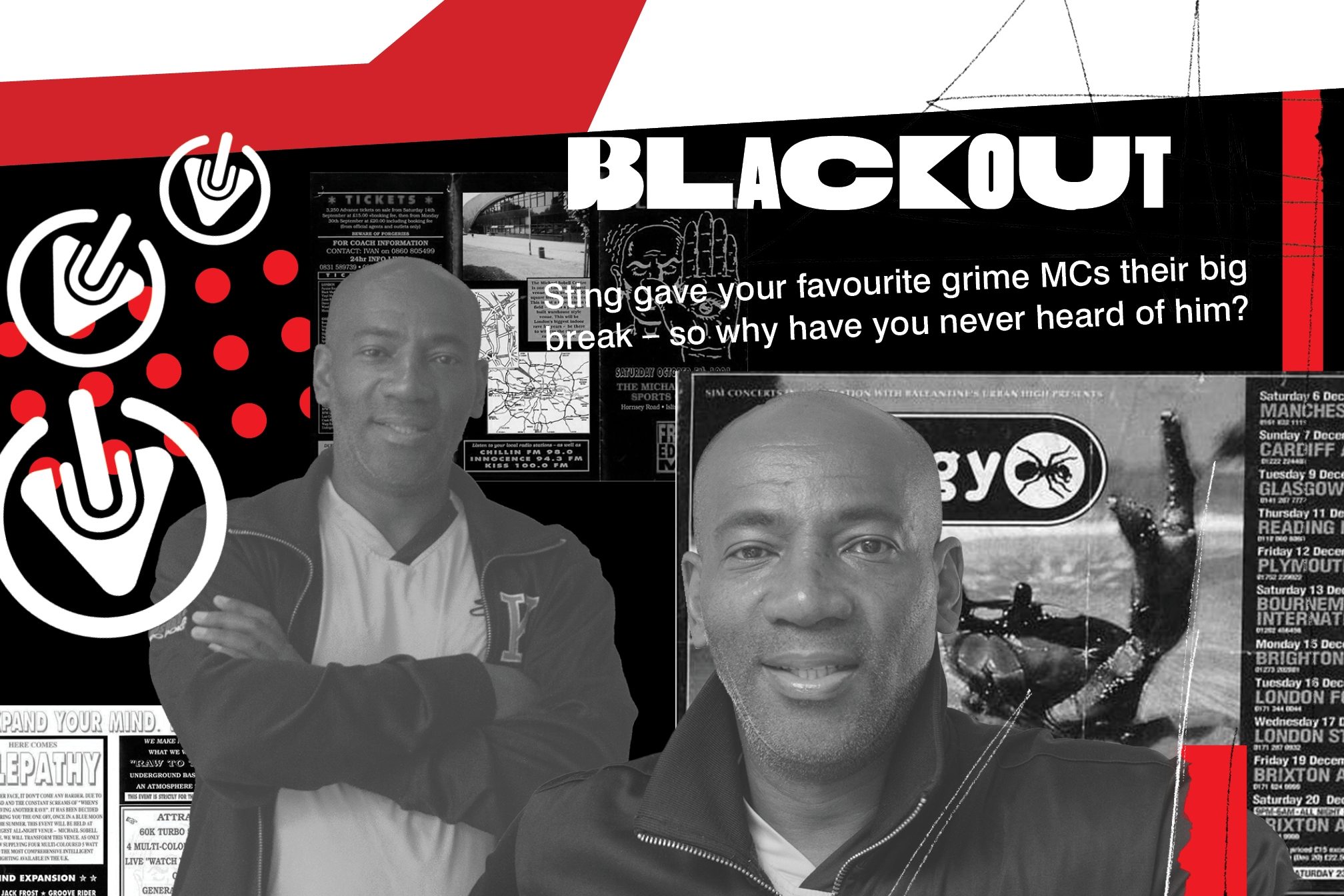

Sting gave your favourite grime MCs their big break – so why haven't you heard of him?

Kwame Safo presents the history of Sting, the London entrepreneur behind the legendary Deja Vu radio station and the seminal early 90s Telepathy parties that helped to birth jungle

Even now, I have to make sure that there hasn’t been anything written about Sting already. The fact that there is so much information on the internet covering grime and yet none on the person who created one of the genre’s most influential platforms is inconceivable. I can accept “gaps'' in music history but too much talent has passed through the East London pirate radio station called Deja Vu for a wider audience not to know about its importance. I do my Googles and the only real write-up on Sting is on the station’s website. The blog post is from 2017. Sting has been active in the music industry for over 35 years – and not just in grime. He’s also responsible for Telepathy, one of the first hardcore and jungle raves and venues like Stratford Rex, which is etched into the history of London’s dance music scene and, in turn, the UK’s too.

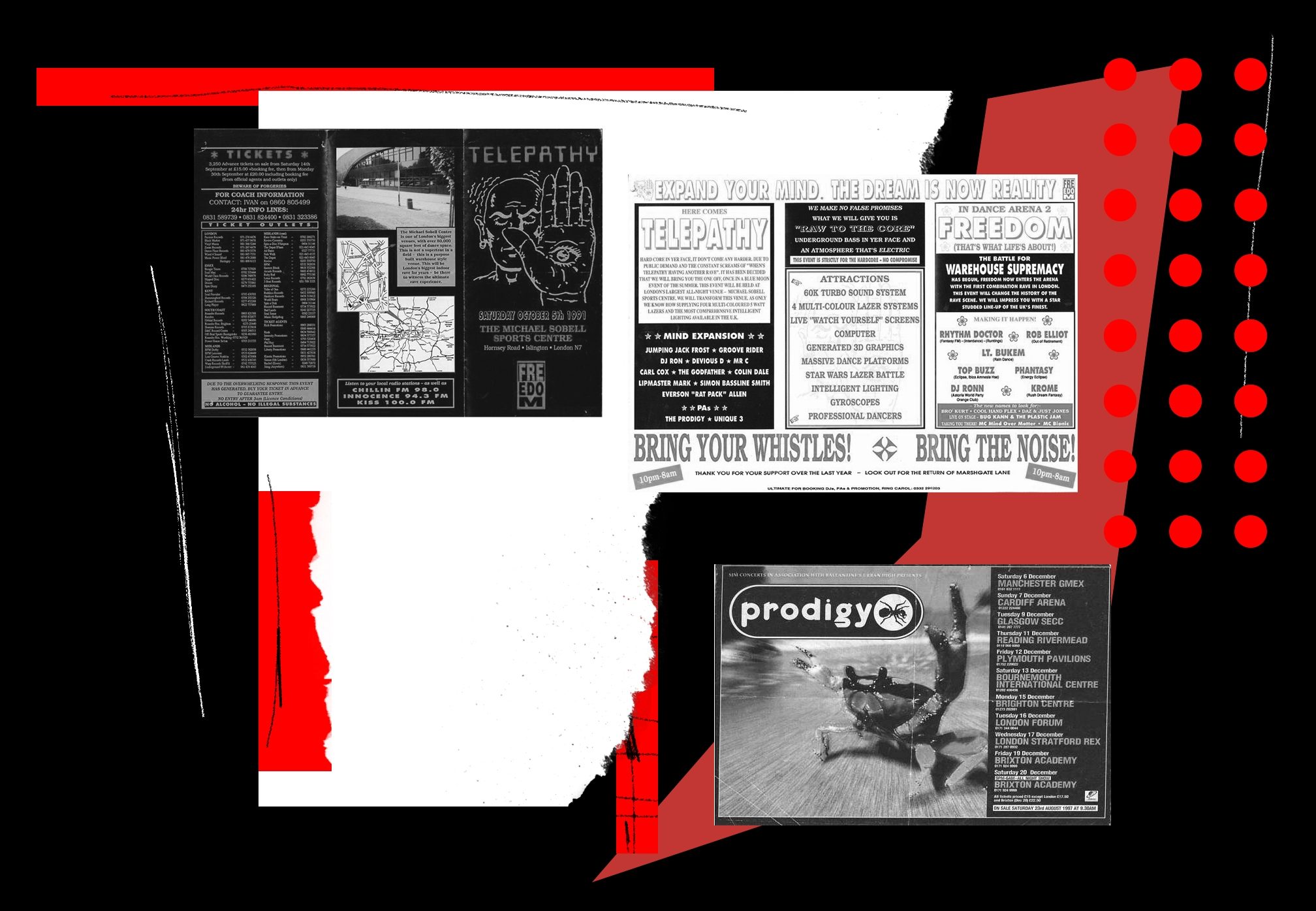

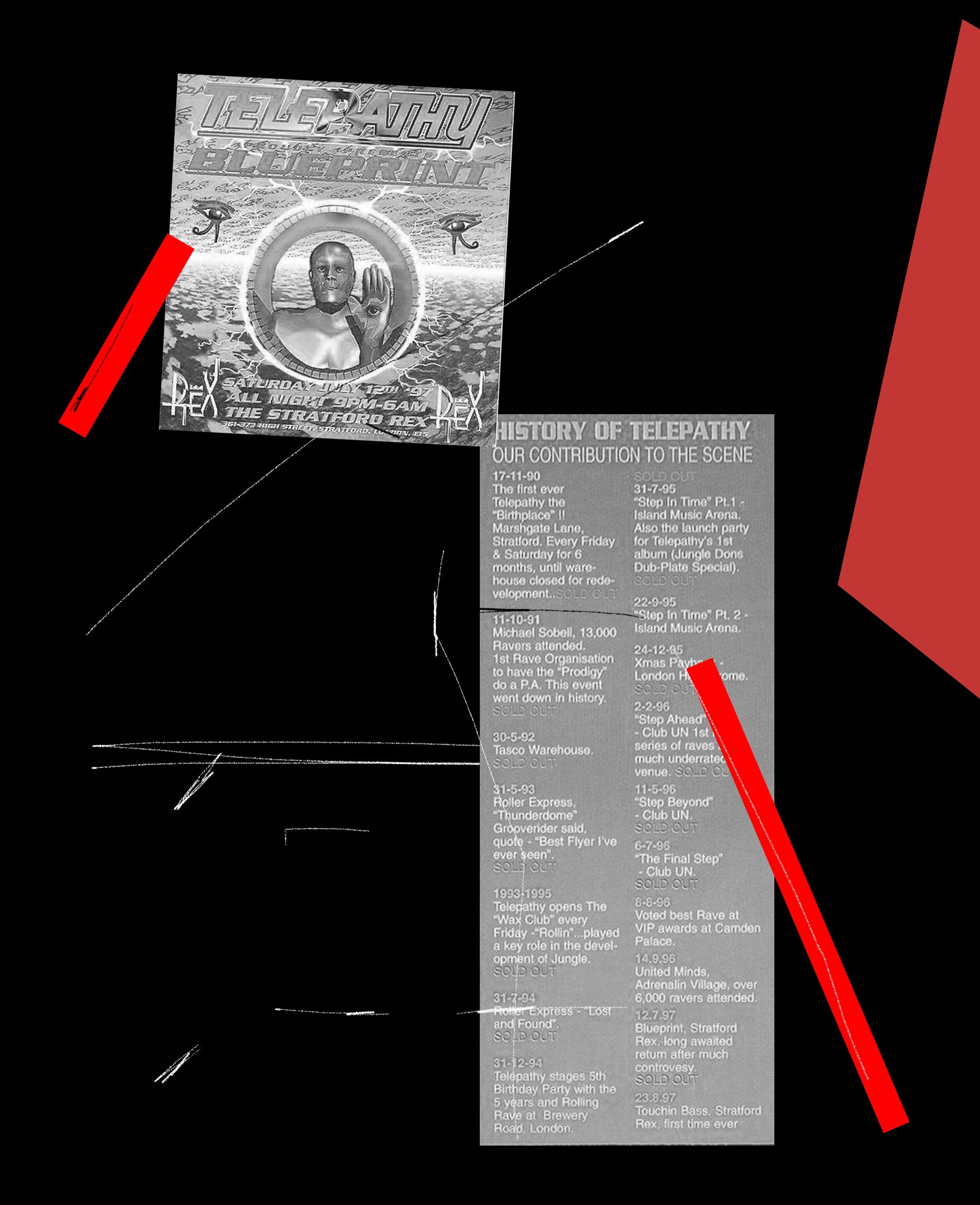

The very first Telepathy was held in Stratford on November 17 1990. It was at Telepathy that The Prodigy got their first London booking. The way Sting discloses this kind information, so nonchalantly, is frustrating. It’s the mark of a music industry professional with too many personal achievements. Running Telepathy and giving The Prodigy their start in the capital is a huge deal – but not to someone who’s been building platforms and running venues for three decades.

I’m going to meet him at the bar he now owns in Hackney, The Windrush Bar & Kitchen, aptly named after the incredible contribution of the Caribbean migrants known as the “Windrush Generation” who came to England on the Empire Windrush passenger ship. The ship arrived in the United Kingdom from Jamaica in 1948 and its passengers would change British culture forever.

He opens the shutters of the bar and we head inside. He’s brought some of the memorabilia he can find to the bar. Sting has got most of the old Telepathy flyers but some of them also exist online on fan sites. I show him something I literally found 30 minutes ago on my phone while waiting for him, digging for online information to help illustrate his fascinating journey. It's an image highlighting all the different dates of Telepathy. “Where’d you find this?,” Sting says as he takes a closer look at the image on my screen. The image is important because it shapes a better understanding of the development of the jungle movement. Sting is sorting me out a drink and while doing so he confirms that in regards to the name jungle being synonymous with the sound, Paul Ibiza would be the most accurate creator of the iconic title. However, if jungle was definitively classified around 1994/1995 then the formation and curation of the sound was happening a lot earlier which at Telepathy, which is why the rave is such an important cornerstone in the formation of the genre.

Read this next: Rave crews are using apps to escape the police

The first Telepathy happened at Marshgate Lane, a large warehouse venue of which Sting was the proprietor. A Black club owner in 1990 was a remarkable feat even by today’s standards. The events would draw people from all over the capital to the raw and diverse melting pot of electronic sounds which as of yet had not been given its labelling. The Telepathy nights themselves were carefully curated by Sting, who hand-picked DJs who would deliver a style of rave music befitting his own aspirations for the music’s direction. Sting would book acts such as Jumping Jack Frost, Andy C, DJ Ron, Grooverider, Bryan Gee, DJ Hype, the late great Stevie Hyper D, Nicky Blackmarket, Kemistry & Storm, LTJ Bukem, Ray Keith and many more.

I want to know more about The Prodigy playing their first London gig at Telepathy. “I did an event in Birmingham or Manchester and there was a promoter up there, I think his name was Majika, he might have been managing The Prodigy at the time and back then Telepathy was big, the brand back then was up and down the length and breadth of the country. If you was into rave you knew about Telepathy and Majika actually approached me and said ‘I’ve got this band Prodigy I want them to do a live P.A down in London’ blah blah blah and I was like, ‘yeah gimmie some tapes’ and yeah, they was just bad! I booked them and they came down to Telepathy, now at this point nobody really knew about Prodigy, they were an aspiring band, and I can remember it like it was yesterday. They came. And there were some live bits and pieces incorporated into what they were doing so it wasn't just a P.A and the whole place just erupted!”

The Prodigy performed for Sting at Telepathy at Waterden Road in 1990. Then again at Michael Sobell Centre, Finsbury Park on Saturday October 5 1991 to a crowd of approximately 13,000 people. Sting himself would later become the owner of the Stratford Rex venue, Stratford, East London. He found himself blocked by some of the larger corporate entities who were attempting to freeze him out of the live music economy and subsequently struggled for numerous months to book a credible live act at The Rex to build consumer momentum. Liam Howlett of The Prodigy would receive a call from Sting about his new venue in Newham. The phone call was met with an effervescent Liam saying how grateful he was to Sting for giving them their first booking in London and would be happy to play for Sting. In 1997, The Prodigy did a date at Stratford Rex as part of their Fat Of The Land World Tour – for free.

Read this next: Dance music documentaries you need to watch

Sting tells me about the strong afrofuturist imagery in Telepathy’s flyer designs. Much of it is the brainchild of artist Junior Tomlin. “Back then it was a little bit taboo to represent Black images for what was perceived to be a predominantly a white clientele,” Sting says. It seems that the problems he faced back then are still relevant to Black promotions today. “The racism, and all of that, was there. But this is why a lot of these fuckers don’t like me. Because you know what? I dont give a fuck! Who wants to come, who doesn’t want to come – This is a Black organisation, with Black representations and connotations of what we do! Because you have to understand that the drums and the bass that you’re so in love with, they come from a place of Blackness! You can’t disassociate yourself from where this sound originates and comes from.”

Sting's overall outlook has always been an unapologetic one. An outspoken entity in the world of conformity which rewards participants with overground commercial success. But to achieve that recognition, compromises have to be made and Sting has never been willing to do that. Especially if the compromises are cultural. “Because without the Blackness, it doesn't exist,” he says, finding his rhythm. “Yes we’re a Black organisation and we promote ourselves as such and I don't compromise, I’m not gonna compromise, because that would be dishonest to myself.” Was there ever any doubt in his mind putting out flyers with imagery which could have had a polarising effect? “We used to put out our flyers and our raves were still jam!”

This just shows why the Blackout Mixmag content and this feature on Sting is so important and timely. Black ingenuity and resourcefulness is at the heart of the contemporary British music narrative. But if that’s the case why have so few figureheads and pioneers from it’s most uncompromising place been visible to the wider music market? Brutal honesty and uncompromising attitudes in the music industry don’t fair too well and Black professionals who exhibit these attributes are normally labelled as “difficult to work with”. Complete omissions of people like Sting are wholly disingenuous and draw parallels to the problems with historical revisionism in UK culture as a whole, not just in music (this was beautifully articulated most recently by West Indies Cricket legend Michael Holding in the summer live on Sky Sports).

Sting acquired the Deja Vu radio station in 1997 and he moved the station to his club in Waterden Road. Initially Deja was set up as a means for Sting to be more cost effective in his ability to market and promote his events. The plan was to use Deja Vu to air the adverts promoting Sting’s events and create a revenue stream from the adverts of other promoters who wanted to utilise the station’s fast-growing listenership.

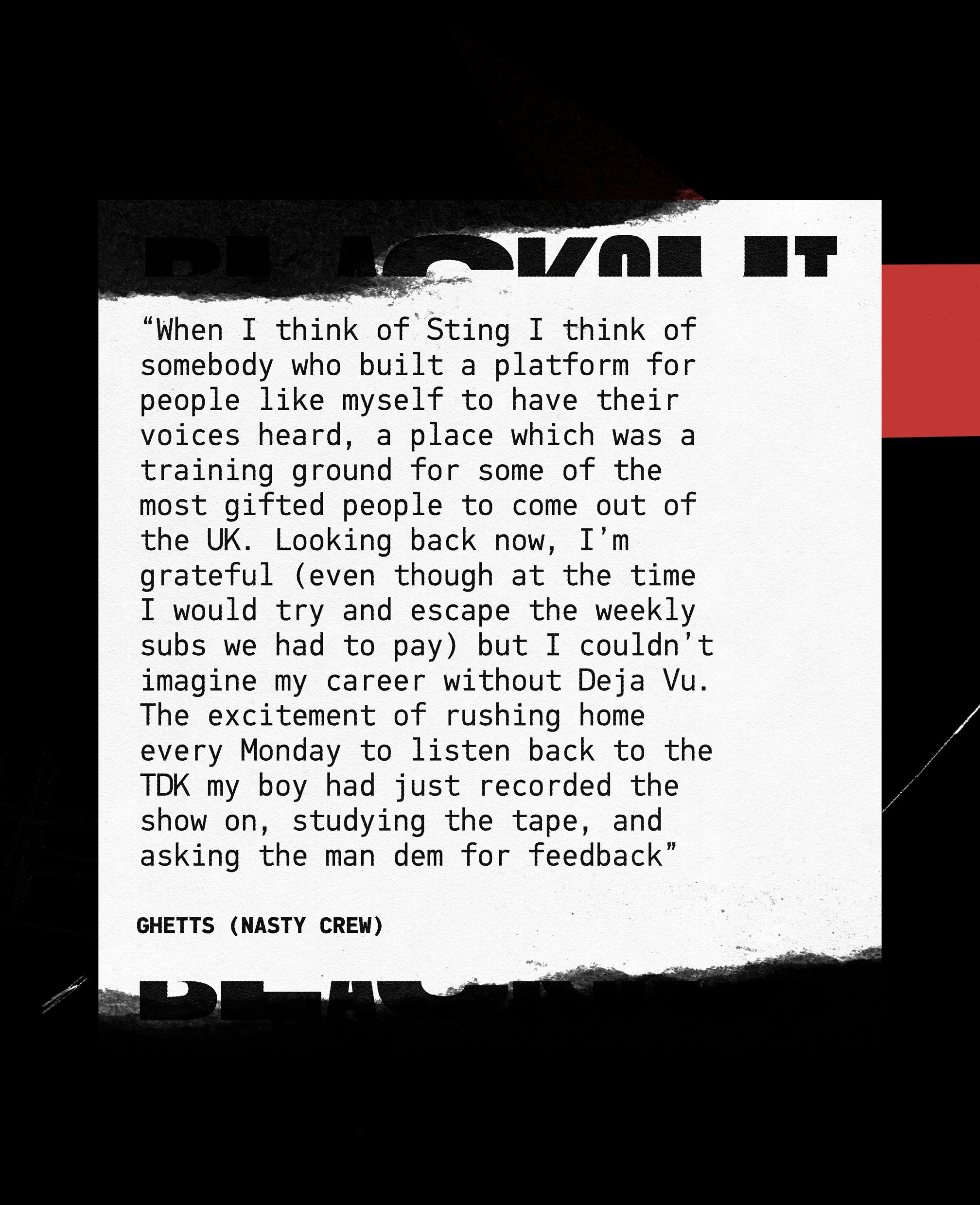

We talk next to some of the memorabilia he has brought to the bar. One is a plaque for Dizzee Rascal’s debut album ‘Boy In Da Corner’ released in 2003, which subsequently won him the Mercury Prize. The plaque is made out to Deja Vu, the station Dizzee would frequent on Monday nights at 8-10PM as a guest of Nasty Crew. Members of Nasty Crew include DJ Mak 10, the late great Stormin, Sharky Major, Armour, Hyper MC, D Double E, Kano, Ghetts and Jammer.

Read this next: The MCs and DJs at the forefront of Japanese grime

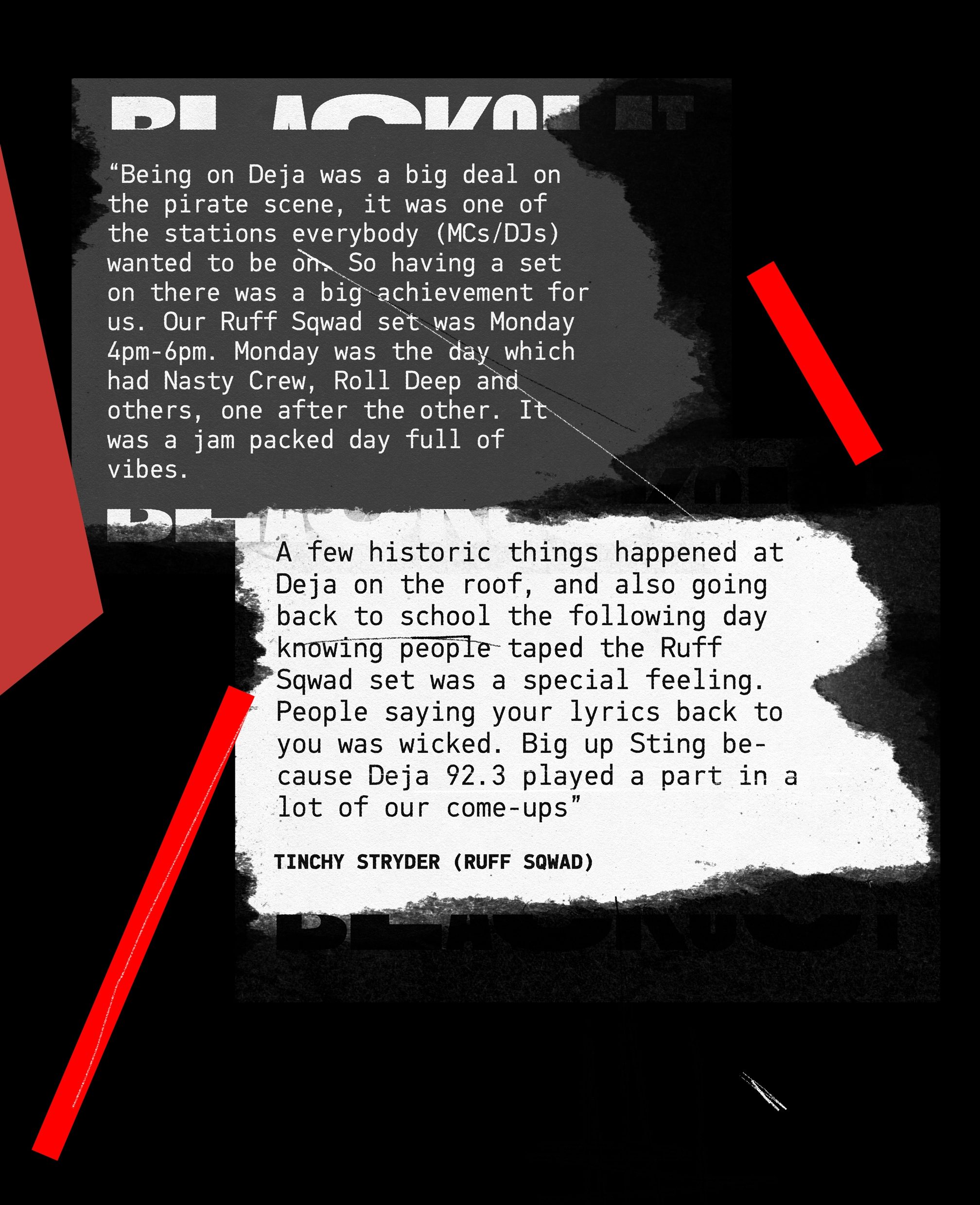

The list of on-air contributors to Deja Vu FM reads like a who’s who of underground music royalty: Ruff Sqwad (Tinchy Stryder, Rapid, Dirty Danger, Slix, Fuda Guy, Shifty Rydos, DJ Scholar, DJ Begg), Tu Tuff Crew (Spidey B, the late great Babycham), More Fire Crew (Lethal B, Neeko, Ozzie B), East Connection (Demon, Jookie Mundo, Nappa, Nicky Slimting, Diesel, Double O, Maximum, Fresh, Shizzle, Ryder, Preshus, Major Ace and Maxwell D) Slew Dem (the late great Esco, Chronik, Rage, G-Man, Tempa T, Waifer, Shorty Smallz, Kraze). Of all the UK club genres on the station, grime especially had much of its golden years on The Roof, the Hackney Wick location of the pirate radio station and most iconic of all the places Deja Vu broadcasted from. This was situated more specifically on the roof of Club EQ, Stratford, a premises which Sting was the owner of. Much of the visual footage on Youtube captured on the roof was down to Troy Miller (DJ A Plus). His visual series Practice Hours and his Conflict DVD are more important now more than ever to grime to help new, younger audiences understand the energy and environment the genre existed in. One of the most legendary clashes caught on camera between Dizzee and Crazy Titch at Deja 92.3FM was courtesy of Troy’s camera work and the alumni of the station frequently label themselves as the Class of Deja (it’s even a recent song title by Kano featuring Ghetts and Double E, all of who had residencies on the infamous frequency).

There's another plaque with us on the table of the bar. It’s for ‘Speakerboxxx/The Love Below’, the fifth studio album from Outkast. I knew Deja Vu and its DJs had supported many Black music genres in its years but I’m curious as to why he chose to bring this plaque. He explains that the D.T.I, the authoritative body sent to combat illegal radio transmissions, had sent Deja Vu FM correspondence, a warning of sorts, in regards to Deja and its listening figures in the South East of England. Deja Vu FM, a pirate radio station, was the third most listened to radio station in the whole of the South East. Kiss FM was first with Choice FM coming in at second place. The plaque was to recognise the success and influence the station was having on mainstream buying behaviour. Deja Vu definitely was a force of nature.

Sting is incredibly active these days, he hasn't stopped moving. Whether it’s owning his five clubs: Club EQ, Stratford Rex, Tara’s Nightclub in Marshgate Lane, TKO, Astirs, Club Zen in Milton Keynes and the Windrush, to also having a hand in multiple successful promotions like Telepathy, Frisky Bizness, Life Utopia and Young Man Standing. His drive is phenomenal, but it makes sense. As an original renaissance raver the requirement to master multiple skill sets and a shrewd business acumen would have been thrust upon him as a necessary means to survive in the entertainment industry.

Being unapologetic in his delivery of rave culture has undoubtedly meant much of Sting’s achievements have been omitted from the mainstream UK music conversation. The fact that not one article exists on Sting after over 35 years of industry experience poses some serious questions. None more so than about the way in which music journalism has not necessitated a desire for true in-depth knowledge and information across the full spectrum of important eras, such as grime. Grime MCs were a welcome condit for rebellious teens and 20 somethings, mesmerised by the candour of a whole group of young Black men from some of East London's poorest boroughs (Newham, Tower Hamlets and Hackney). Grime was marketed through the frustrations, bravado and angst in their music. Attempting to intellectualise their struggle and work on ‘the why’ would have undoubtedly exposed individuals like Sting and his philosophy from an early stage. It’s a stark contrast to the level of interest shown to stations such as Rinse FM who were able at will and with relative ease to command a contextualisation in the press.

Putting the importance of Sting’s contribution into an editorial feature is practically impossible. But to put it bluntly, if you remove The Roof from Club EQ, you remove the safe space young Black men adopted to hone their craft and become the huge household names they are today. The creativity is romanticised but the infrastructure which provides the security and capacity to create is sadly overlooked. Hopefully the words here will bring deserved visibility to the man who should no longer be a myth to the UK music industry.

Kwame Safo is a DJ, broadcaster, label head, producer and music consultant. He is the Editor of Mixmag's Blackout Week and you can follow him on Twitter here

Read this next: Get the best of Mixmag direct to your Facebook DMs