Features

Features

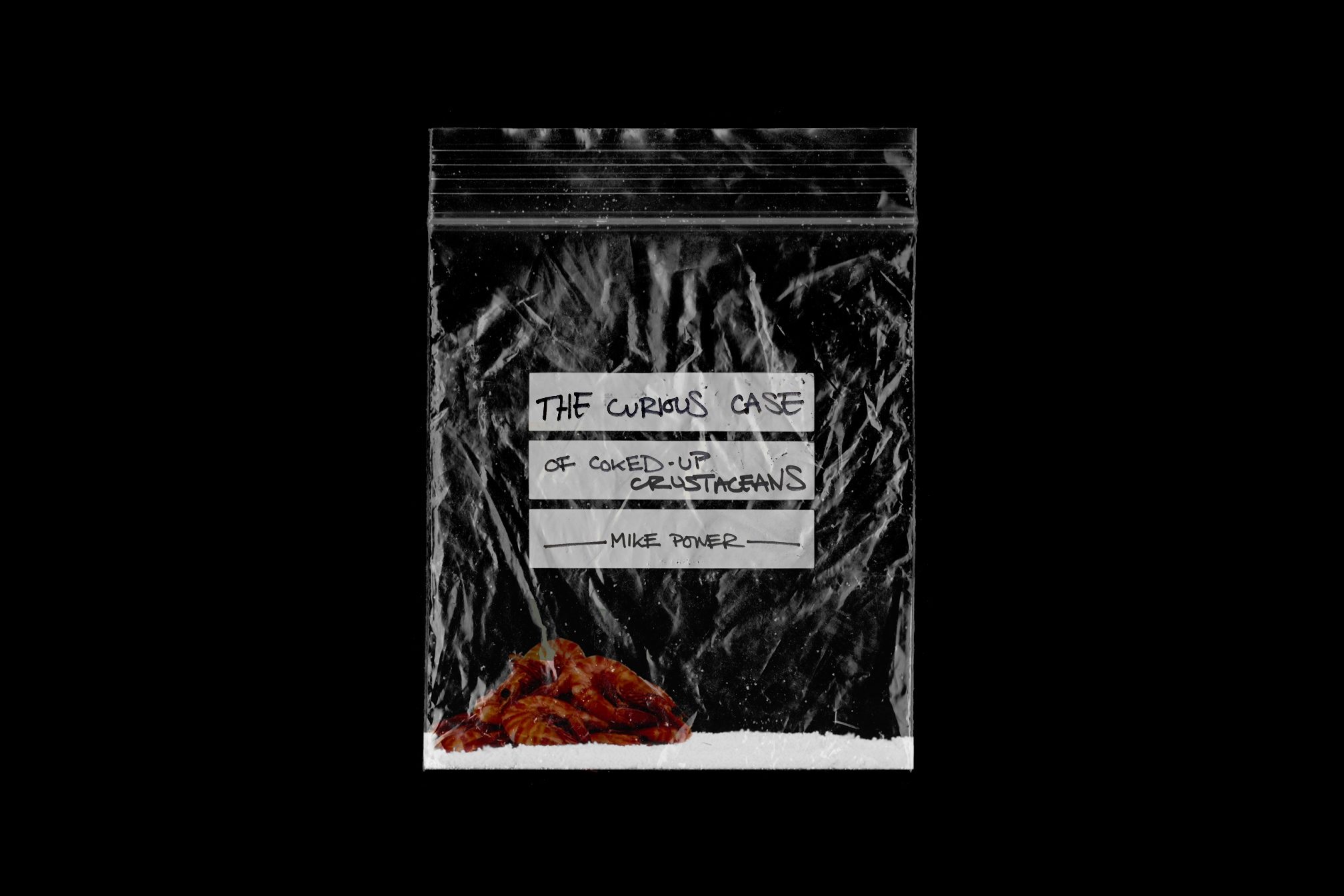

Prawn coke tale: Why Britain's 'drug problem' is mainstream media scaremongering

The reporting on Suffolk's coked-up crustaceans reflects the media's scaremongering tactics

In 1997, the poet Murray Lachlan Young's prescient poem: Simply Everyone’s Taking Cocaine detailed the rising number of people in the UK who were getting bang on it: everyone from plumbers to peers and priests and police were snorting it up, he wrote.

One group the poet didn't identify as keen consumers of cocaine were the crustaceans of Suffolk. But as researchers revealed last week, every sample of freshwater shrimp found in the rivers of that county in research carried out by ecotoxicologists from King’s College London contained traces of cocaine – and every newspaper duly ran with the story.

You’d be excused for thinking you might go fishing in the rivers Alde, Waveney, Stour, Gipping and Deben with a net to catch yourself a stimulating dinner. But, alas, it was just a classic variation on a media drugs scare story.

Newsrooms across Britain regularly run pieces about cocaine being found in the most unexpected of places: from the nappy changing stations in Peppa Pig World to the Houses of Parliament's toilet or in the writhing bodies of eels. All of them are true, to some extent, but there’s always more to the story than meets the eye.

And the regularity of their appearance speaks more of the media’s readiness to present drugs as more prevalent than they are – thus justifying continued police targeting of users.

How did the cocaine get into the prawns? Cocaine users throughout Suffolk metabolised the chemical, and went to the toilet (very shortly thereafter, in many cases). Scattered throughout the catchments of these Suffolk rivers are small wastewater treatment plants that discharge into the water courses, where it finds its way into the prawns.

The Suffolk study collected samples from five catchment areas, and 15 different sites across the county. Cocaine was found in all samples tested, at an average rate of 5.9 nanograms per gramme. To put that into perspective, a gramme of cocaine contains 1,000mg. Each milligramme contains a million nanongrams. So researchers actually found 6 billionths of a gramme of cocaine in each gramme of prawn. It has not yet been calculated how many would be required to get prawns high.

Lead author, Dr Thomas Miller from King’s College said: “Although concentrations were low, we were able to identify compounds that might be of concern to the environment and crucially, which might pose a risk to wildlife", though he did note that "the potential for any [harmful] effect is likely to be low”.

This vital work in the field of ecotoxicology helps us understand the impact of man-made chemicals entering the food chain, informing policymakers on better ways to manage the environment. But newspapers will never let the facts intrude upon a good story.

Criminologist Robert Ralphs, of Manchester Metropolitan University, says the media spin on the story is an attempt to present drug use as increasingly widespread, if not ubiquitous, when statistics show cocaine use has not increased enormously in recent years.

“This is the latest in a long history in the UK of media misrepresentation of the scale of illicit drug use and the harms, from amphetamine use in the 60s and 70s, ecstasy and Leah Betts in the 90s, crack babies, through to 'Spice’.” says Ralphs.

However, in particular reference to cocaine, this has been accompanied by an interesting new narrative that has moved beyond the 'drugs are bad' on a personal level to cocaine users being blamed for underpinning drug wars in Latin America, to recent increases in knife crime amongst young people. This takes it to another level in terms of drug users’ part in environmental harm.

"If you have equipment of the required sensitivity and the motivation to go looking, you should not be surprised to find cocaine traces in any body of water anywhere near places that humans live and urinate and defecate. Or change nappies. And the real danger to wildlife isn’t the drugs, but the packaging they come in," says Ralphs: “I would expect that our waters are more at risk from the plastic snap bags that many of these drugs are sold in rather than the metabolites of drugs that enter them.”

Danny Kushlick, of drug law reform group Transform, says academic researchers might feel encouraged by the media’s “obsession” with illegal drugs to seek out pollutants such as cocaine, noting that every report overlooked the fact that many of the contaminants found in the study were legally prescribed pharmaceuticals.

"This looks like a typical case of university media teams sexing up research studies for mainstream coverage,” says Kushlick. “In this case the presence of cocaine, rather than haloperidol (a prescription anti-psychotic also found in their study) which was flagged, no doubt for the eye-catching news hook. Many parts of the media also appear to have a pathological urge to hype the harms of illegal drugs. The study doesn’t really tell us anything about the prevalence of use, so it might be of interest to experts in shrimp biology, but less so to anyone concerned with patterns of drug use or policy."

So, will the prawns of Suffolk soon be arrested for possession of an illegal, Class-A substance? After all, the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 does not specifically state which species is prohibited from being in possession of its long list of banned chemicals. Will we soon see police divers gathering up netfuls of coked-up crustacea and sentencing them to the maximum seven years in jail? Will all applicable fines be imposed? The Suffolk Constabulary were unavailable for comment.

Mike Power is the author of Drugs 2.0 and a regular contributor to Mixmag. Follow him on Twitter

Read this next!

Cocaine and ketamine have been found in Britain's river wildlife

Insta-gram: How British cocaine dealers got faster and better

Why is cocaine so strong at the moment... and where's it all coming form?