Cover stars

Cover stars

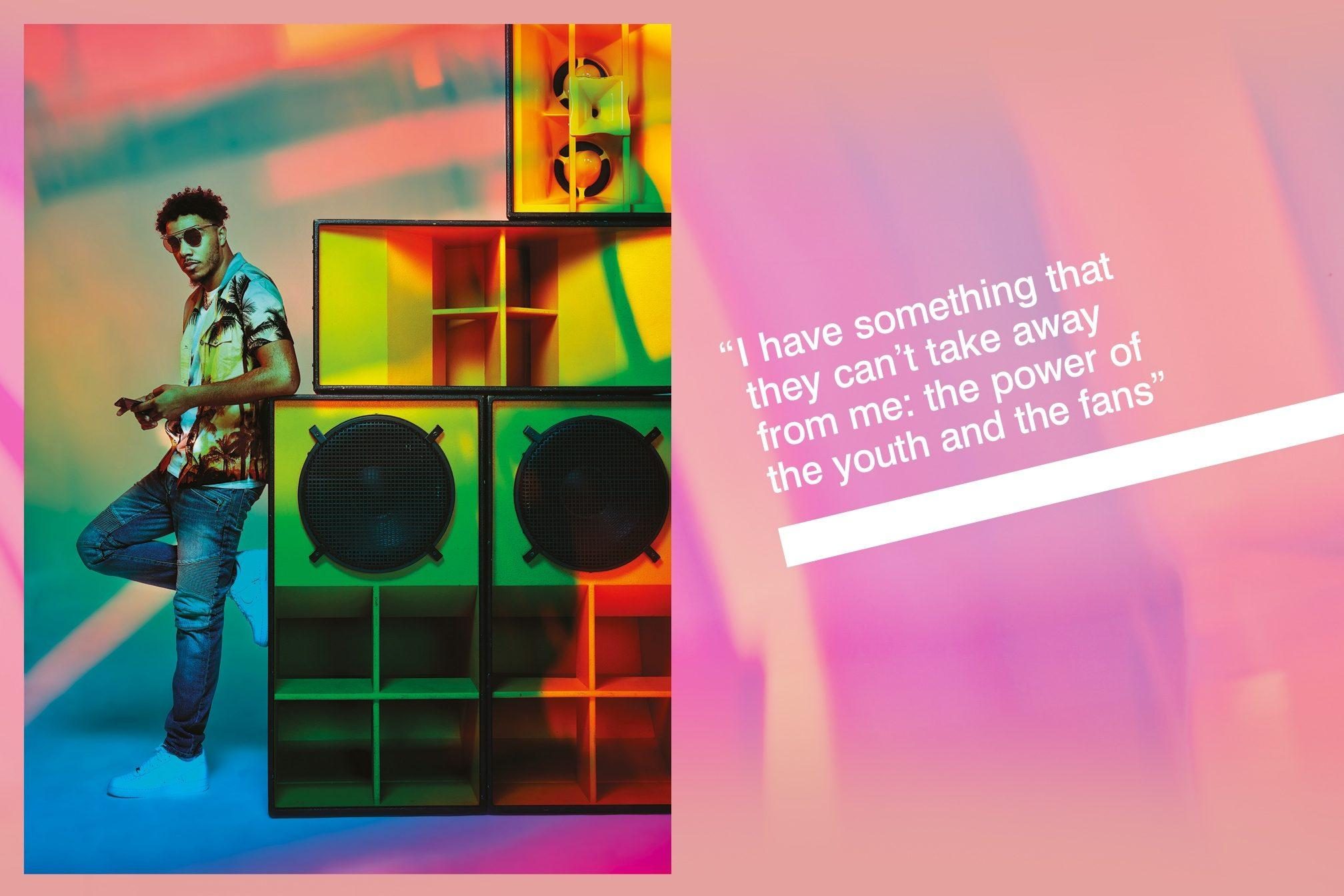

"The power of the youth": AJ Tracey can't be stopped

Beyond the hits and moshpits, AJ Tracey is an artist unafraid to speak out about politics or injustice – or open up about his mental health

“Mosh pit. Flying liquids. Energy.” AJ Tracey ’s describing a typical festival set in three words. Well, kind of. The West London MC relishes festival season and is looking forward to doing a victory lap around European summertime following the Top 3 chart success of his self-titled debut album. “I just like everyone going wild – I’m more for the anarchy side of things,” he says, with a mischievous laugh.

We’re living through a golden age of UK lyricism, and the fast-talking, designer tracksuit-sporting 25-year-old is firmly at the fore of it, having staked his claim with a slew of scene anthems dating back to 2015. For this generation of artists – including, but not limited to, elders and young guns like Skepta, Giggs, Stormzy, Dave, Fredo, J Hus, Not3s, MoStack and Little Simz – harnessing grassroots support and landing in the charts with uncompromising music is second nature.

There are a dozen pairs of designer trainers in the hallway of AJ Tracey ’s Chelsea flat. They speak of success, sure, but also where he came from: a kid surreptitiously selling chocolate bars at school in order to save up for a pair of £50 Air Force 1s with a sky blue sole that all the older guys were wearing, including early inspiration and mentor Ice Kid. He saved most of the money before his friend Jammz gave him a tenner to get him over the line, and he legged it to the store straight after school to cop.

This dogged determination also propelled his interest in the art of MCing. Growing up in the estates around London’s Portobello Road and Ladbroke Grove, AJ would hit local youth clubs in order to lay down his earliest tracks. Having access to recording equipment and a belly full of food was a blessing. “I wasn’t broke to the point where I couldn’t eat, but it’s helpful. If they’re giving you free meals it’s taking stress off your mum,” he says. “If I missed my dinner, there’s not another dinner. So if I needed to go to the youth club and they’re feeding me, that’s great. It helped a lot of impoverished kids in the area."

We’re sitting on AJ’s sofa facing a large flatscreen telly that’s got Fortnite on pause. He’s in the middle of a tour promoting his album and is a little worn out, but basking in the glow of making venues bounce ’n’ mosh nonetheless. Two nights ago he sold out the 5000-capacity Brixton Academy, delivering a tightly choreographed, time-coded show backed by visuals that referenced each of his tracks.

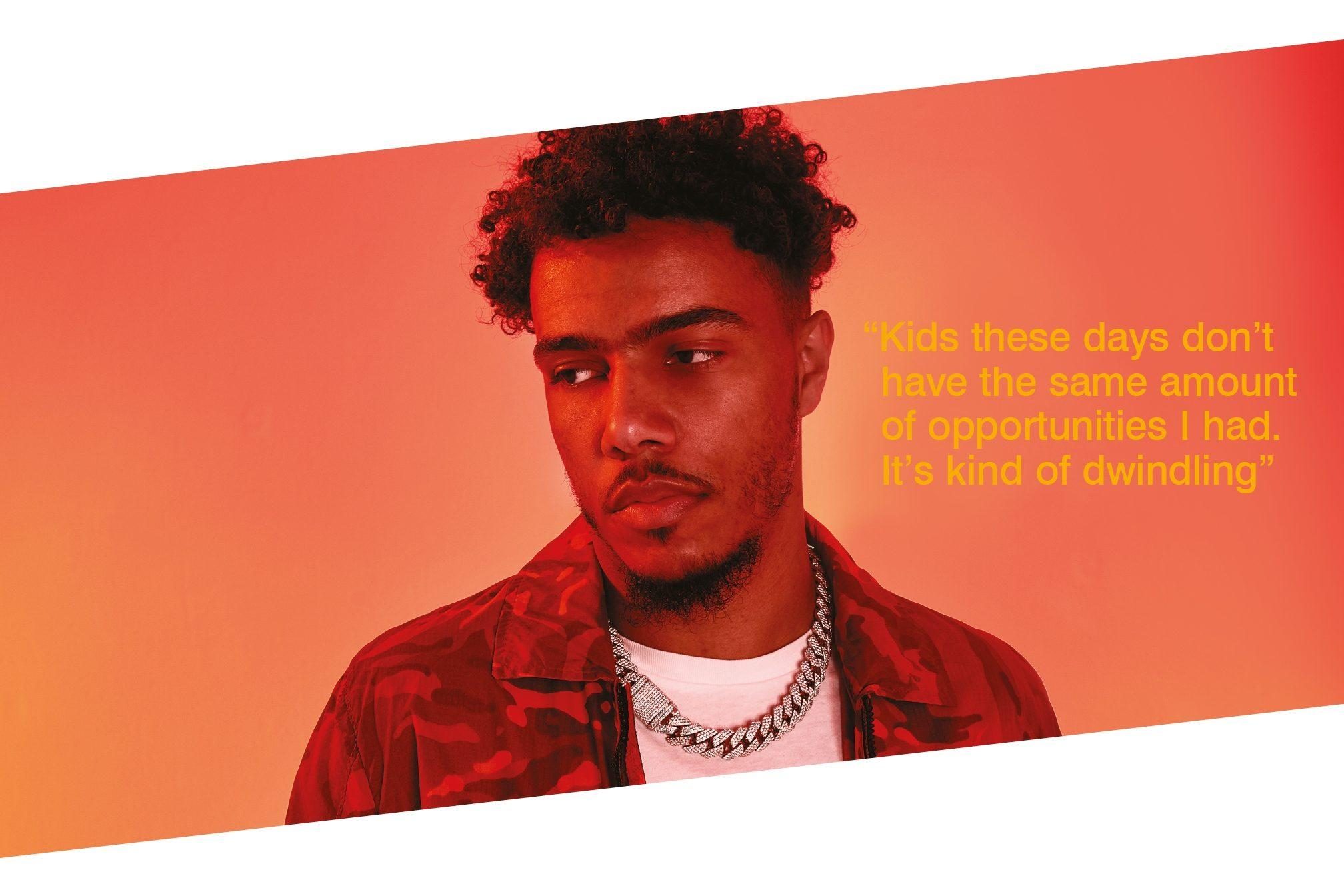

Would his rise have been different if it wasn’t for those youth clubs? “Maybe I wouldn’t have come up. I was also recording in a trap house. You could be recording in there and police could come in and you’d go to jail. I feel sorry for kids these days, because they don’t have the same amount of opportunities I had. Even before that, my mum and dad say they had more opportunities than us, so it’s kind of dwindling.”

Since AJ started laying down YouTube freestyles and uploading tracks to SoundCloud at the start of the decade, 760 youth clubs have shut and 4,500 youth workers have lost their jobs across the UK. “You see all these knife problems? I think youth work is genuinely the key,” AJ says, before we even bring up the stats. “Some kids are not made for education, and it’s inevitable that they’re not going to fit into the system, so what do we do? If there’s no youth work and no youth clubs for them to go to they’re gonna be on the street. And if they’re on the street and they have no money, they will try to commit crime. That’s just a fact; there’s nothing [else] for them to do.” The decline in youth services caused by years of Tory austerity has coincided with a 51 per cent rise in knife crime convictions among 10–17 year olds in England and Wales, and research shows that under 16s are most likely to be stabbed straight after school finishes, which is also when they would one have been heading to hang at a youth club.

AJ was caught in the trap for a while. Just as the AJ Tracey star was starting to rise, his entrepreneurial spirit and voracious approach to music became intertwined. He was shelling appearances on Mode FM, Deja Vu, Rinse FM and BBC 1xtra while also trying to make ends meet. “I just wasn’t living correctly,” he says of his lifestyle at the time. “I was in the streets, with the mandem, just doing what I could to make money and live. I wanted my mum to be comfortable and I didn’t want to be broke.” Some of his lyrics from the time are delivered with dark humour, like a bar from a radio set that goes “I’m born to trap / Trap in a bus, in a car, on a bike / Or a trike”, the kind of smart juxtaposition he learned from peer-turned-collaborator Merky ACE. But there are poignant moments, too, like the blink-and-you’ll-miss it “Had to jump off road because my mum couldn’t take it” from his Fire In The Booth, viewed 5.6 million times. “My mum didn’t bring me up like that,” he says. “So for her to find out I was doing certain things, she’d just be disgusted. I just didn’t want to do something to upset her.”

He worked a month at a barbecue restaurant but quit after his first pay cheque because management treated him like shit. He did a year at uni but dropped out because he wasn’t feeling it and wanted to take music seriously, something his mum co-signed. So when he got paid £150 to do a show, the cash vindicated all of the hours of practice, late nights at radio and sheer belief in himself. “My confidence comes from my mother. She always boosted me up. She instilled it in me,” he says. His reaction to a braggadocious old bar – “Rinsing MCs without water / Who’s this MC? Ask your daughter” – solidifies his point. “In my opinion, the only three MCs who are better than me, or as good as me, are P Money, Skepta and Chip. And that’s flow, mic control and ability. I don’t doubt people are great rappers, lyricists, wordsmiths. But as an MC, as a mic controller, I’m telling you: there’s no-one else even close.”

You could say it was always meant to be. AJ Tracey – real name Ché Wolton Grant (after that Che) – was born in Central Middlesex Hospital, same as Dizzee Rascal. His Welsh mum was head of youth work for Lambeth and a dedicated pirate radio DJ who filled the house with jungle, drum ’n’ bass and NWA. In a move calculated to create his own lyrical flow that other MCs wouldn’t have the skill to copy, AJ would spit atop his mum’s music, which zipped along at speeds of up to 180bpm. This living room bootcamp was inspired by anime series Dragon Ball Z: “When the fighters are training for a big fight, they train in a gravity room, so it’s such heavy gravity that if you can fight under these conditions, when you come out in normal air, you feel super light on your feet,” he explains. “My reasoning was, if I can spit on drum ’n’ bass and get it perfect, when I spit on a grime set, it’s a piece of cake – which it was.”

His Trinidadian father, whom AJ vows never to name, had a career as part of a UK hip hop group in the 90s, switching him on to Nas, Mobb Deep and KRS-One. “Sonically we’re nothing alike,” AJ says. “But in terms of having the drive to do that, and showing me how to write lyrics when I was young, obviously he inspired me.” AJ’s godbrothers, Dice and Moss, also tutored him from the age of nine, and he appeared on stage at the BRIT Awards aged 12 as a backing dancer for Gorillaz. His little brother introduced him to the music of Dave, which would lead to the pair’s breakout 2016 collab ‘Thiago Silva’. And AJ was schooled in UK garage in the estate in which he grew up, which was awash with the sound when he was younger. The stars align, as Mike Skinner would say.

The toughest love came from his Trinidadian grandma. “Their morals in the Carribean are like, ‘Yo, education is the be all and end all. I showed her an invoice, like, ‘Look, I’m getting paid a thousand pounds for a show.’ She said, ‘Why is anyone paying a thousand pounds to see you?!’ That’s genuinely what she said. She was like, ‘As long as you put money aside and live reasonably, that’s cool.” And is he? “Yeah, of course. I’ve got investments that no-one even knows about. I think it’s wise for every young artist to invest in other things. I’m not saying I’m not a good MC, but you could make the best music in the world and people get tired of you. Eventually your time will run out.”

It’s 2019 but black male graduates are still paid 17 per cent less than their white colleagues and, in the case of elite unis, don’t even get offered a place at all. Was his gran simply warning him that he’d have to work twice as hard? “My gran was genuinely worried about my life. She just thought, ‘If my young, mixed-race grandson doesn’t have an education or a way to make it through the corporate ladder, then how’s he going to survive?’ My white nan, she just doesn’t see colour. You might say something to her like, ‘Gran, I can’t go and sit in that all-white pub in the Midlands because I’m black,’ and she’ll genuinely be like, ‘Why?’ She just sees me as her grandson and wants me to do whatever I wanna do and be happy. My black gran is the same, but she sees the dilemmas I’m gonna run into as a black youth.”

He ran into one of these dilemmas during an interview with Chloe Tilley on BBC2. She said he didn’t cast strong women in AJ Tracey videos, after the ‘Psych Out!’ visual was shot in the Magic City strip club in Atlanta. “Because a woman chooses to strip doesn’t mean she’s not strong. The girl who’s in my video on the ceiling doing acrobatics – bruv, I can’t do that, that is a talent, that’s crazy,” he says. Tilley then accused him of being in a gang because he appeared alongside a crew of friends in ‘Doing It’. Shortly after AJ’s run in with Tilley, fellow MC Dave faced a Twitter backlash for ‘Black’, a track championing the personal and shared experience of the colour of his skin. The list goes on, from drill artists banned from making music by the police to a recent government report showing that rap and grime gigs are still being discriminated against by local councils and authorities. What’s it like navigating this climate? “I have something that they can’t take away from me, which is the power of the youth and the fans. Because of that, you can’t stop me from making money, you can’t stop me from making music – you can make my life harder, but you can’t stop it. As long as we acknowledge that they’re doing it and speak about it, then it’s fine. People are gonna see these lot actively trying to stop the black youth from prospering and this is how we get around it, by talking about it, highlighting it, saying it’s stupid and moving on.”

AJ has a track record of clapping back against injustice. He’s criticised the government and its response to the Grenfell Tower tragedy, has urged young people to vote Labour and peppers his tracks with quickfire political statements that reference his dislike of Nigel Farage, police profiling, knife crime and the shit he’s had to deal with as a young black man. But essentially he sees his music as an escape. “For me personally, if you turn on the TV and put on the news and it’s ISIS, Grenfell, ‘We don’t want foreigners in our country’, we’re leaving Europe, Trump does something stupid – everything’s negative and sad and depressing and I feel like, especially with young males, our mental health is not great, so that’s not really helping. Obviously we need to stay in tune with what’s going on, but if that’s the one source of information and it’s all negative then you need some escapism. I just want to be someone who brings happiness to people’s lives.”

His fans are wild for the cocktail of hedonistic word-play and raucous beats that he pours smoother than his favourite drink, Hennessy. “[With] ‘Butterflies’, the radio stations were telling me to take ‘backshot’ and ‘nigga’ out and it’d be a hit. I didn’t take either out and it was a hit. You don’t have to do [what they want]. But it depends how much everyone is on your side. Because everyone is championing me, I can get away with saying things. I try not to censor myself because what I write first time is what I want to say.” He toasts the finer things in life, brushes off rivals and haters with a cheeky glint and paints vivid images of his heady sexual encounters. He denies his graphic lyrics are sexist or disrespectful. “I’m a very sexual person. My mum hates it, but it is what it is, innit. I’m not saying things that are negative or derogatory, it’s just a bit coarse, a bit vulgar. [And] I don’t listen to rock, either, because that’s definitely much worse.”

At the start of our conversation, we joked that the 10,000-capacity Alexandria Palace would be next on the AJ Tracey hitlist. He smiled, as if the thought had crossed his mind before, but didn’t bite. He’s got other things he’s keeping an eye on, anyway. Away from the hustle ’n’ hype, AJ is just trying to maintain normality – and avoid the battles with mental health that have stopped him from doing shows, making music and even leaving the house in the past. “It happens, man. The more people who talk about it, the better. Kids who experience the same thing that I do will go, ‘I’m OK, I’m not weird or different’.” He brings up one of his tweets that asked, “I wonder how many successful artists who are currently making music are genuinely happy?” It’s a good question. Is he? “I think it’s a spectrum: all the time I’m OK, and sometimes I’m happy. I’ll be happy and come down and sometimes I’ll go down and come back up. I’ve been to the doctors and they said I have depression and anxiety, but they said it’s normal, don’t bug out about it, just try to stay healthy. Sitting around, smoking weed, drinking loads of alcohol and not leaving your house is really not healthy. Sitting on Instagram and looking at your negative comments, not healthy. Trying to look at what other people are doing, not healthy. I have my lane, I have to be grateful that I’m not in the streets trapping. Being grateful is one of the keys to being happy. When you’re content that’s when you’re happy.”

It seems that AJ Tracey knows as well as anyone that life isn’t just moshpits and hits – even as he gets set for a summer of excelling at both.

AJ Tracey’s self-released album, ‘AJ Tracey’, is out now

Seb Wheeler is Mixmag's Head Of Digital. Follow him on Twitter

With thanks to the Unit 137 soundsystem

Read this next!

Novelist: Writing his own rules

Rap hero: J Hus is the optimistic soundtrack to Britain's turbulent times turbulent times

Steel Banglez is the one-man production powerhouse behind the new wave of UK hip hop