Features

Features

The roadmap to change

Kwame Safo sets out a plan for real change in the music industry

The Black Lives Matter movement has galvanised many in the music industry to consider their part in the exploitation of the Black community. At this point, solutions should spearhead the conversations being had by those behind the scenes. It’s time to get practical and take a measured path to fixing this.

We have to redress the economic and institutional imbalance felt by Black musicians and Black people working in the music industry. This ranges from the more obvious and visible lack of representation of Black acts at large festivals and prominent venues, discrimination of club promotions endorsing events with large Black clientele, to a media in which music production from Black acts is met by vicious microagressions targeted at challenging the quality of the art made. Black producers in dance music especially are snubbed with the belief that “they just need to make better music”. I myself was knocked back for an A&R position at a house label (a music discipline where I have over 15 years experience in) on the grounds they were “looking for someone with a little more experience”. This feedback was received after I had been hired by the label for information on acts I believed would return a successful investment.

Over time the custodians of Black music are slowly shifted from the democratic spaces of the dancefloor into more nefarious and less understood environments such as office spaces and boardrooms. Forensic insight is necessary to explain what is at play here and has been for many years – sometimes this is not an easy task because of the lack of statistical data on the subject and the lack of understanding of systemic racism by the white people who make up the majority of the music industry workforce.

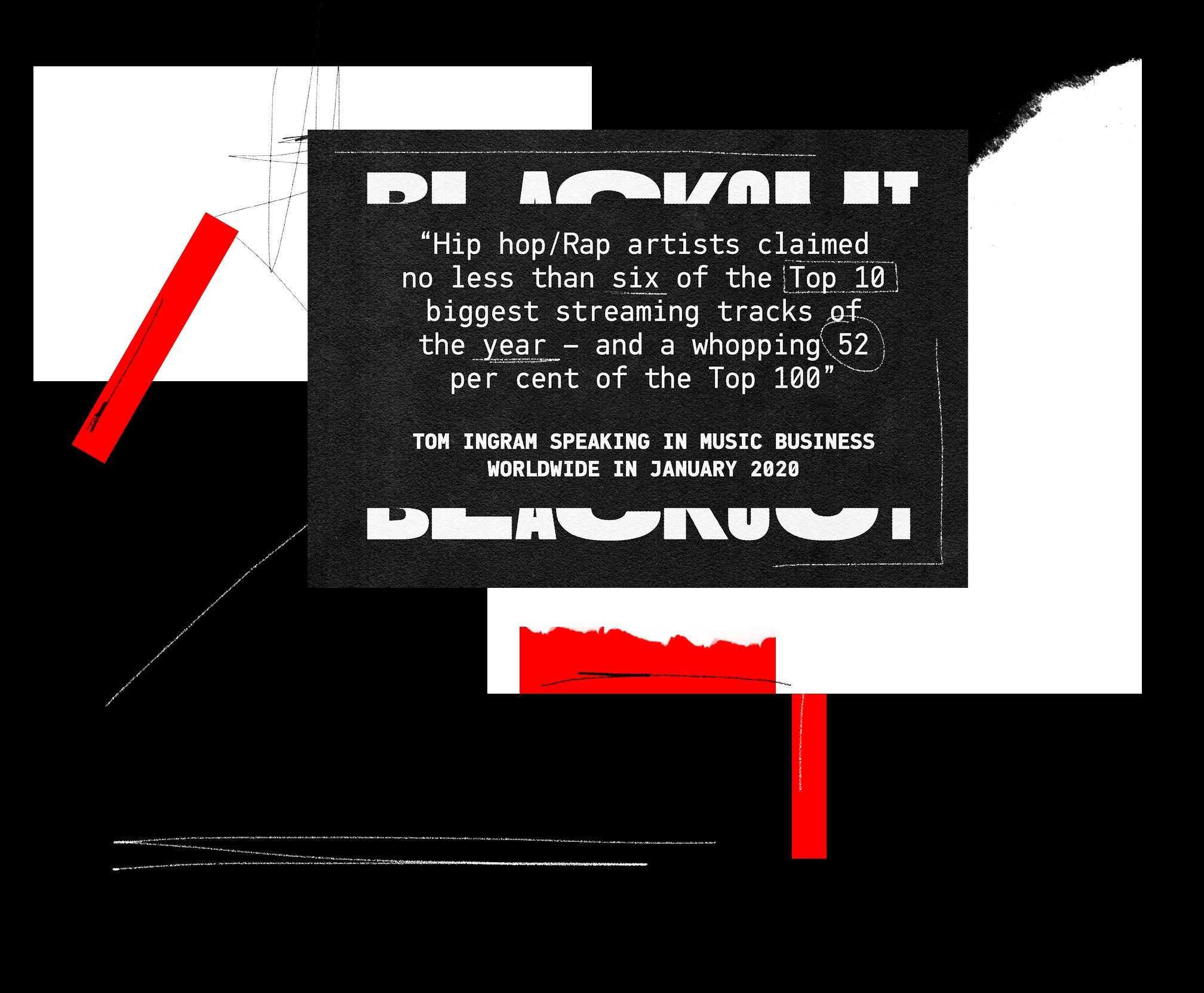

Although genres historically rooted in Black creation have been diluted into ever more ambiguous titles such as IDM or EDM, one thing that is certain is that Black music has a very clear and traceable influence over popular music and is the basis for many of the genres that we listen to today.

We are at the beginning of a much wider and long-term conversation over the part that major labels, radio stations and media channels have played in the exploitation and subjugation of Black talent. But, as mentioned, it's hard to quantify the exact Black contribution to the music industry in a numerical value. For instance, neither PRS (collecting for songwriters in the UK) or PPL (collecting for performers) hold data on the ethnicity of their memberships. This in itself was a shocking discovery and hints that a robust investigation into the artistic makeup of the music industry could reveal some embarrassing truths.

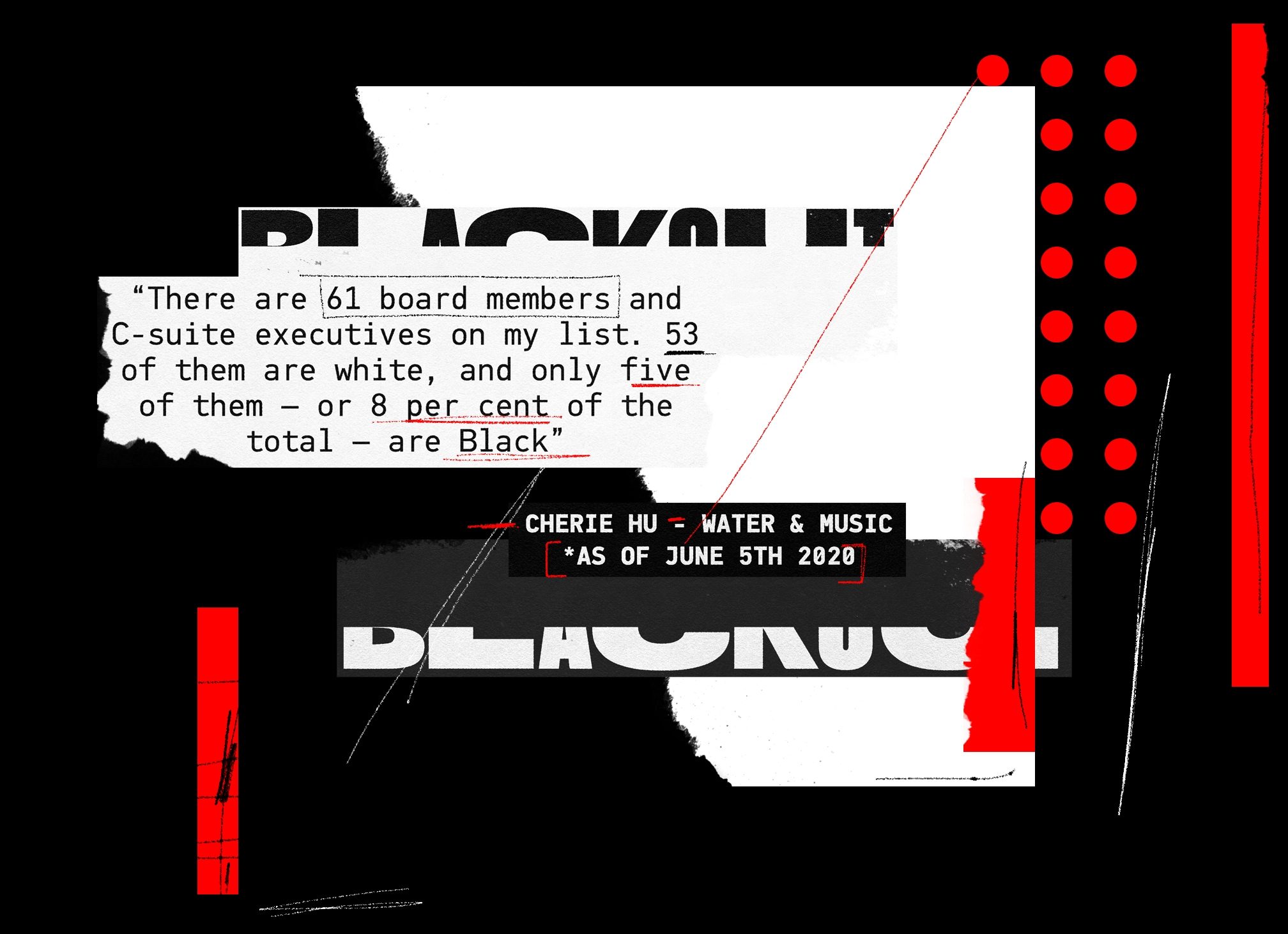

The number of Black executives working in music is disproportionately small compared to the amount of Black people working throughout the music industry at artist level. Cherie Hu is a researcher and writer of the newsletter Water & Music. In June, she followed on from a series of threads on Twitter regarding racial disparity in the music industry to illuminate the gulf of Black representation in the boardrooms of the big three major labels (Universal, Warner and Sony) and the top two concert promoters (Live Nation and AEG).

Below board level, figures from 2017 revealed that only 12 per cent of the $43 billion generated by the music industry that year made its way back to artists. This is outrageous and especially shocking for Black artists given their vast contribution to music and influence over it.

The music industry is full of horror stories: record labels like Trax and Black electronic artists like Adonis who haven't seen a penny in over 34 years; Black women cajoled into invisible session-singing in the hope they will be later rewarded with full support and resources, but rarely seeing anything in return; Microaggressions which over time wear down the resolve and capacity to meet “professional” expectations and are only ever eased due to a painful compromise in artistry; Faux meritocratic structures which work to disillusion Black artists who are trying in vain to market records in white corporate spaces. Even when you make allowances for the tumultuous nature of the music industry and degree of luck that an artist needs to ‘make it’ regardless of race, it still doesn’t account for the lack of considerate behaviour and opportunities afforded to Black people.

The Black working class can be broken down into many subsections based on classifications and perceptions. This should be taken into account when hiring from Black spaces and be considered inline with the objectives of that appointment. Black as a social class sits largely within the working class sector in the United Kingdom. Households with higher rates of renting social housing were from the Black African (44 per cent), Mixed White and Black African (41 per cent) and Black Caribbean (40 per cent) ethnic groups according to an English Housing survey conducted in 2017.

The privilege enjoyed by white people in particular within the music industry is steeped in the poor understanding of the diverse nature of the African diaspora itself. It attempts to satisfy the needs of such a rich cultural grouping with a ‘one size fits all’ solution but also refuses to educate on very basic issues within the Black community such as colourism and the different nuances and intersectionality of Black life. For example, someone could be a Black individual from a working class group, but also intersect with the LGBTQ+ community and have a perspective on the industry based on their own sense of belonging. This means the appointment of this person may not garner the desired results as the individual may not enhance their racial background in their role as opposed to their gender identity. The Black experience within an organisation needs to be understood on a molecular level to truly empower both workers within the industry and also organisations to avoid tone-deaf responses. Appointments designed for cultural progression and equity need to be based on the values of the candidate.

Music has long existed as an avenue of financial independence, a way out of relative poverty and a possibility to accrue generational wealth for the Black community. Other working industries do exist, but the barriers to entry for music and sport are comparatively low and are inundated with tangible and visible Black success stories. There is enormous Black participation in many arenas of popular music and pop culture (seen in Black marketing power on platforms such as Twitter, Tik Tok and Snapchat) and this representational dominance only helps to encourage even more Black engagement in these creative spaces. The amount of Black people contributing to the creation of Black music, often to change their socio-economic circumstances with the objective of being “signed” to a major, leads to the goal of an advance payment but no understanding of the recoupment stipulation, leading to long term Black debt in the music industry.

The Major Labels have always used the advance and recoupment deal as a tool. To a young artist the offer of a big cheque has long been the way labels tempt them into signing deals that are very unfavourable. It works for the hugely successful artist because they manage to pay off the debt and then get offered another huge advance. But this method of doing business has long distorted the market. Right now the music of hundreds of artists is out there making money for labels but very little – and in some cases nothing – for the actual artists. Labels are rarely, if ever, held to account. This money is simply lost to the artist in question and the community they live in. There are thousands of contracts in effect today that were signed in perpetuity in the 20th century (going back as far as 1985) that are unchallengeable. In the light of Blackout Tuesday, how does the music business claim that it wants to effect change and yet not do something to address this huge problem?

The Major Labels would argue that they’ll speak to anyone who comes through their door and asks to renegotiate those old deals and we should be promoting this activity. But lawyering up and walking into a big corporate building to face down an experienced negotiator should not be necessitated even if it is affordable. These deals should be repaired blanketly. Forgive the unrecouped debts of any artist you haven’t made anything new with for ten years and move every artist onto a minimum 30 per cent streaming royalty rate. This will have an instantaneous redistributive effect. Beggars Banquet did this for their artists a few years ago, so we know it can be done.

Black artists, when compared to the size of the Black population, make a disproportionate amount of the music available in the UK and the US. Which means that if the music industry is exploiting all artists, it is disproportionately exploiting Black artists. But record deals don’t have to be exploitative life-of-copyright recoupment deals anymore. They can be fixed-term license deals with profit-sharing. This way advances can continue, but the artist isn’t set at such a punitive, indebted disadvantage.

The prevailing way the world listens to music is streaming and the streaming system is built to reward the biggest rights holders. The master rights (the recording) take the lion’s share of the money and the major labels take the lion’s share of those. Some people estimate that artists get less than 5 percent of the subscription. We may have grown used to streaming and the way it pays very little to artists, but Universal and Sony both grossed one billion dollars each in the first quarter of 2020 from streaming. Goldman Sachs, the investment bankers, deliver regular reports. One such private report states that Vivendi, the owners of Universal Music Group, are one of the surest investments out there with huge growth on the horizon.

How did we fall into this trickle down position? Where an industry worth billions of dollars is not enriching the communities it draws from? Where is the sense of responsibility and a social contract? The Major Labels seem entirely comfortable to make extraordinary profits without addressing any of this. How many of their shareholders are Black?

We know that many corporations have started to think about sustainability and social responsibility. Can music companies even begin to talk about Black Lives Matter if there is little evidence of social consciousness and reinvestment outside of the advances they hand out and describe as ‘investment’? This model has to reform. When you make these kinds of super profits, those working in finance have a name for it: rent. These companies are making rent on the rights of musicians when we should all be sharing in growth and profitability.

Any genuine roadmap to addressing Black inequality must begin with companies sincerely addressing the existence of exploitative practices within their systems, especially the Major Labels. They quickly pulled together 100s of millions for Black Lives Matter funds when the protests blew up (Warner music also had a major share offering about to happen which may have compelled them to act).

How should these funds be used? We all welcome investment in community projects, but, setting aside exploitative business practice, for this money to have a genuine effect it needs to be set to genuine structural change. Some possibilities:

❏ Research and data discovery on ethnicity in the creative and business sectors.

❏ Leadership development and angel investment funds so that barriers to entry are overcome at all levels.

❏ Free legal advice

❏ Supply of music business education and resources.

❏ Small grants so that Black artists can become members of PROs (Performance Rights Organisations) and start to earn money from their compositions and performances.

Then we come to the thorny topic of representation. In boardrooms and talent development sectors representation is often offered up as the cure-all answer. It’s incredibly important to have diverse voices in the room, but there are other issues to consider and questions to ask:

❏ Tokenism is problematic. We see the elevation of one or two Black A&Rs, for example, but we know there is a glass ceiling beyond which they cannot rise. Tokenism at boardroom level has perhaps held back progress, rarely addressing the exploitation at the heart of the record business.

❏ Black industry workers are often only engaged to work with hip hop or Black music (ignorantly classified as “Urban”). A Black A&R in charge of folk music is no less incongruous than a white A&R in charge of hip hop. This thinking is patently racist.

❏ Because you’re Black it doesn’t necessarily mean you came from a Black community and are going to elevate others from that community. A Black public schoolgirl may well be more detached from the Black music community than any white girl from an estate in South London. It’s a tough and complex question, but it’s clear that the most need to level up and elevate is from the Black community that we’re more familiar with: The one that is commonly underprivileged and has less access to opportunity. There is a need for companies to actively develop talent of all ethnicities for executive positions who also demonstrate progressive thinking. Those with the intent to address racial bias in decision making.

❏ Maybe there’s more to why a Black people in the music industry can’t get into the top jobs (there’s precious few Black women and women in general in these roles too). If an executive class of white men is running the biggest companies and they never leave their jobs how can anyone get in there? Should anyone who has been in a top job for over 10 years simply get out of the way? Boards have fixed terms, why don’t executive positions? And is nepotism something that should be investigated at executive level in the Major Labels? Is it ‘jobs for the boys’? What is the best, most constructive way to critique and challenge this behaviour?

We’ve already seen some good developments. Broadcaster and music producer Mistajam has already begun a practice within his own radio show to credit every vocalist on a track. This takes care of the longstanding issue of singers (especially Black female singers) not featured as the credited artist on the artwork. This could become an industry standard enforced at production level and would hopefully be adopted by all radio stations. It could be demanded at a radio plugging level that the participation of any singer be known within the initial promo run. If the singer did however forfeit their accreditation to appear as a featured singer, that could easily be divulged to any producer or DJ in receipt of the record. Recent conversations on Twitter by Kelli-Leigh (uncredited voice behind ‘I Got U’ by Duke Dumont feat Jax Jones and ‘I Wanna Feel’ by Secondcity) and Shingai (uncredited voice behind ‘Hey Hey’ by Dennis Ferrer) have seen stations like Electric Radio endeavor to correct information, alongside Glasgow based Atmosphere Radio to at least inform radio presenters and listeners as to who is actually behind the music.

The idea that the business of music has to persist with exploitative measures at the expense of Black artists is a ridiculous notion which exists because it has gone largely unchallenged. Beyond the organsiational movement itself, Black Lives Matter is language understood within Black spaces to redress the societal imbalances post slavery. White supremacist structures are created to dangle the carrot of economic reward and escapism from relative poverty, while raffling off Black creative prowess to the highest bidder. Economic emancipation (for not just Black, but for other low socio-economic groups) can be achieved through learning more about the inner workings of the music industry and getting a more detailed understanding about how the business of music works. Having more agency within the music industry will bring control of it to the Black community who created much of the music that is being sold in the first place and stop the Major Labels repurposing Black pain for financial earnings. The commodification of Black music in the record business has to exist hand-in-hand with its role as the art of the oppressed. Removing the soul of Black music does as much damage as the lack of remunerations and pay-gaps.

The use of statistical data to measure equality comes with its own risks, especially in societies where Black representation is the minority like the United Kingdom. The last Census in 2011 marked the Black contingent in the UK at around 3 per cent of the overall population. Considerably lower than the percentage of the Black diaspora in the United States (which sits around 13.4 per cent according to the last US census in 2019). Companies and large organisations, especially within the media, tend to believe their workspaces should at least be a microcosm of wider society. That the level of diversity and inclusion should at the very least be in line with the representation of said group in society. This is a false equivalency as 3 percent of the music industry is not influenced by Black culture, it’s considerably more. In areas where Black representation isn’t measured accurately, it’s more than likely exploited as there is no grounds to limit Black contributors in those areas. For example, at artist level where it’s widely argued the bulk and most profitable part of the music industry is from Black music, the data in this arena is shockingly sketchy or as of yet undocumented. Black musicians are the ones who fundamentally prop it up creatively and create new artistic movements that are later commodified. The other tiers of the music industry, which define where the profits go or how that artistry is marketed are much less forgiving and restrictive to Black involvement. It's these parts which need to be restructured moving forward, minus the empty platitudes to look socially responsible. The roadmap is here, we just have to change the course we’ve been on.

Kwame Safo is a DJ, Broadcaster, Label Head, Producer and Music Consultant. Follow him on Twitter