Features

Features

“My life changed overnight”: Dealing with sudden hearing loss and tinnitus

For the introductory feature of our Tinnitus Awareness Week series, our guest editor Seb Wheeler shares his experiences with hearing loss, tinnitus, and his journey of mental and physical rehabilitation

Tinnitus Awareness Week 2024 takes place across February 5 - 11. We're joining the campaign with a series of features raising awareness about ear damage and promoting protection. In the introductory essay below, our guest editor Seb Wheeler details his experiences with sudden hearing loss and tinnitus

It’s a sunny Monday morning during the summer of 2016. My alarm goes off and a new week begins. Except it doesn’t, because when I swivel my legs out of bed and try to stand up, my feet feel like they’re set in concrete and the rest of my body refuses to do the get-up-for-work routine my brain is telling it to. I panic instantly, shout for help – “I can’t stand up!” – and then the room starts spinning.

I’m suffering from sudden hearing loss, which is taking my hearing away quickly and without any notice. I didn’t realise it at the time, but while I was sleeping I had lost most of the hearing in my right ear, leaving my inner ear so damaged that any exposure to loud noise would eventually lead to intense tinnitus. It also results in side effects like extreme dizziness (also known as vertigo), vomiting and a feeling of immense pressure in the head.

There are two types: sensorineural hearing loss, which damages the tiny hairs that conduct sound in your inner ear and is irreversible, and conductive hearing loss, where sound is blocked from passing into your inner ear by a perforated eardrum, damaged ear bones or a build up of wax, which is treatable.

I’ve been struck by the former, the onset of which is rapid and brutal and, especially to anyone with a love of music, devastating. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSHL) causes severe hearing loss and deafness (usually in one ear), tinnitus and sensitivity to sound. The damage is normally permanent unless treated with steroid injections at a hospital as soon as possible (a procedure that is delicate and also very painful). I don’t think to call an ambulance – as I lie back down in bed, the room becomes a whirlpool of movement around me and I feel overwhelmed with shock and confusion. I can barely look at my phone let alone talk coherently.

I was 28 at the time and fully plugged into electronic music and club culture, both professionally and in my spare time. I worked for Mixmag as an editor and journalist, was out three nights a week soaking up and reporting on London’s vast and vibrant music scene, and was regularly travelling to Berlin, Ibiza, Amsterdam and other amazing places in the world to write about and document DJs and dance music. I was among the first wave of residents on NTS, my club night Tropical Waste was popping off and I had a decent side hustle playing party music at bars and clubs. I got to DJ superclubs and festivals as far away as Singapore as part of the Mixmag Allstars and had even nailed my first solo international booking in Berlin. As far as I was concerned, I’d made it. Then I got hit with SSHL and all of this evaporated. My life changed overnight.

Up to this point I’d never suffered from any hearing issues or tinnitus. I’d been wearing my custom ACS earplugs for a while and becoming more mindful of my rave/life balance. The only hint that something was up was a faint ringing noise in my right ear that appeared seven days previous and a bout of vomiting and nausea the day before that fateful Monday morning.

Read this next: The 13 best earplugs to protect your hearing in the rave

I was restricted from being near loud music immediately for fear that my tinnitus would become crushingly loud or that, simply, something else would happen to my hearing. I stopped playing gigs, promoting parties and going out to shows. I lost access to a large part of my social life, missed a bunch of beautiful moments that happen in nightclubs and at festivals, and got used to the stomach punch of FOMO at the weekends. I was blocked from opportunities to cover the music I loved. I stopped my NTS residency because the disconnect from club music was genuinely painful and I recognised that I needed to spend time and energy on looking after myself and figuring out what the hell had just happened.

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss happens to 1 in 5000 people a year and usually to those in middle age. There’s very little online about it, apart from standard medical definitions and bleak Reddit threads. It happens seemingly at random and only 10 per cent of cases have an identifiable cause, such as a viral infection, an autoimmune disease or blood circulation problems. It can also be mistaken for Labrynthitis, Ménière's disease or a regular ear infection, meaning that crucial steroid treatment can be delayed or not recommended at all. Dealing with SSHL is a lonely and confusing experience and I’ve still never met anyone else who has suffered from it apart from fellow music journalist Nick Coleman, who wrote The Train In The Night, which is maybe the only non-medical book about it.

It hit me like a ton of bricks. I was bedridden with vertigo for a week, unable to do much but eat bowls of cereal, vomit and sleep. I managed to drag myself to a GP who put the symptoms down to Labrynthitis and gave me a load of pills to ease the dizziness and sickness. I was signed off work for a few weeks and spent most of the summer on the sofa watching The Wire. I could walk but it took months to feel steady on my feet and I was constantly wondering about the ringing noise in my ear and whether my hearing would return. It was a very grey time, a fever dream in which my life had stopped but the world of my friends, colleagues and peers kept turning. At some point I realised that it was probably more serious than a standard ear infection.

I saw a specialist who conducted Rinne’s and Weber’s tests on me using a tuning fork. It’s an old-school process that can tell whether a patient has suffered conductive (a blockage of the ear, for example) or sensorineural hearing loss. The doctor called it immediately: I’d lost the hearing in my right ear and was unlikely to regain it. The news was difficult to take. I remember my world wobbling at the edges, threatening to collapse. Was that it? Are you… sure?! What about work, music, my social life? What about the constant threat of tinnitus? What if something happens to my other ear?

Read this next: 9 ways to make living with tinnitus easier

I lived in denial for the rest of 2016 and into 2017 as I did a seemingly endless series of hearing tests and clung on to the false hope offered by different ENT doctors who all gave me different verdicts (It’s just a nasal blockage! Being around loud music is fine!). In a particularly desperate bout of optimism I tried homeopathic medicine, which is definitely one of the more futile things you can do to treat irreparable damage to the inner ear. After 12 months gathering results and opinions I went to see another specialist, this time on Harley Street in Central London, who confirmed the worst: I’ve experienced a ‘stroke of the ear’, where blood supply in the ear is disrupted and causes damage to auditory nerves. It’s the most coherent diagnosis yet and, finally, a solid explanation. Some closure. The penny drops and I accept defeat; there’s no bringing it back.

In those first 12 months I’d only spoken to one person, the specialist on Harley Street, who understood what exactly had happened to me. After that I was on my own again, incredibly nervous about protecting my ears, scared about losing my mind to tinnitus and wondering whether I still had a career in music. I’d put many parts of my life on pause but now I had to create a new kind of normal for myself. I wasn’t out at clubs and venues all weekend so I used the spare time to get into fitness, learn a new language, do some travelling, rediscover surfing and spend more quality time with friends, who all commended me on my resilience and how well I’d adapted. I slowly gained the confidence to ask people to sit or stand on my ‘good side’, made bashful apologies to people who spoke into my bad ear and found themselves ignored, and spoke openly about my hearing loss to anyone who would, ahem, listen.

On the surface I was doing well. I’d suffered a rare condition but bounced back quickly and was exploring other aspects of life and genuinely counting my blessings (an early coping mechanism was to tell myself ‘at least you’re still alive’ whenever my tinnitus came into focus). In the effort to be brave and move on, I missed the signs of a deeper anxiety and unhappiness. I’d feel dissociation during lively social events when it was difficult to hear; I became listless at work; I lost contact with a bunch of friends because I wasn’t out all the time and I started losing sense of myself and who I actually was as a person. I’d daydream about how happy I'd be when it was all over, when I'd be cured. Every so often worryingly dark thoughts would enter my head after I put the light out to go to sleep. The effects of trauma were catching up on me and I felt lost.

In the New Year of 2018 I decided to seek professional help. I saw my GP who completely understood my situation and referred me for cognitive behavioural therapy via the NHS, where I began to work through my perceived loss of self and personality and start the process of rebuilding how I saw myself and regaining confidence in who I am. I had a really honest conversation with the CEO of Mixmag about how I was feeling and the company helped me enrol onto a course of tinnitus therapy at Harley Street Hearing, an independent hearing clinic that’s fully equipped to deal with the physical and mental effects of tinnitus and hearing loss. Tinnitus therapy taught me to have a positive relationship with the ringing in my ear, helping me to identify trigger points and deal with the multitude of emotions that arise when you’ve got the sound of an explosion in a tunnel on loop in your head 24/7.

I was also interested in holistic therapies and decided to try craniosacral therapy, in which gentle massage of the body is used to relieve stress (and therefore tinnitus). I signed up with Simon Baker, who spent years on the tech-house frontlines before quitting music because of tinnitus and retraining as a therapist. I had several sessions that made me feel incredibly calm and refreshed; while it didn’t have the miracle effect I was hoping for on my tinnitus, it did teach me to be aware of my body and my mind in relation to dealing with the condition and it helped begin a process of mindfulness that I’m still on today.

This combination of therapies made me feel more confident in myself and more comfortable with my condition. I started to rebuild my sense of self and began to come to terms with the sudden, unexpected life shift that happened to me while I was sleeping. I fostered a better relationship with my tinnitus and started to get through social situations without feeling pressured to explain that I’d suffered severe hearing loss in one ear. I started to see a route through life where I wasn’t defined by my ruptured relationship with music or my hearing loss – I could just be myself.

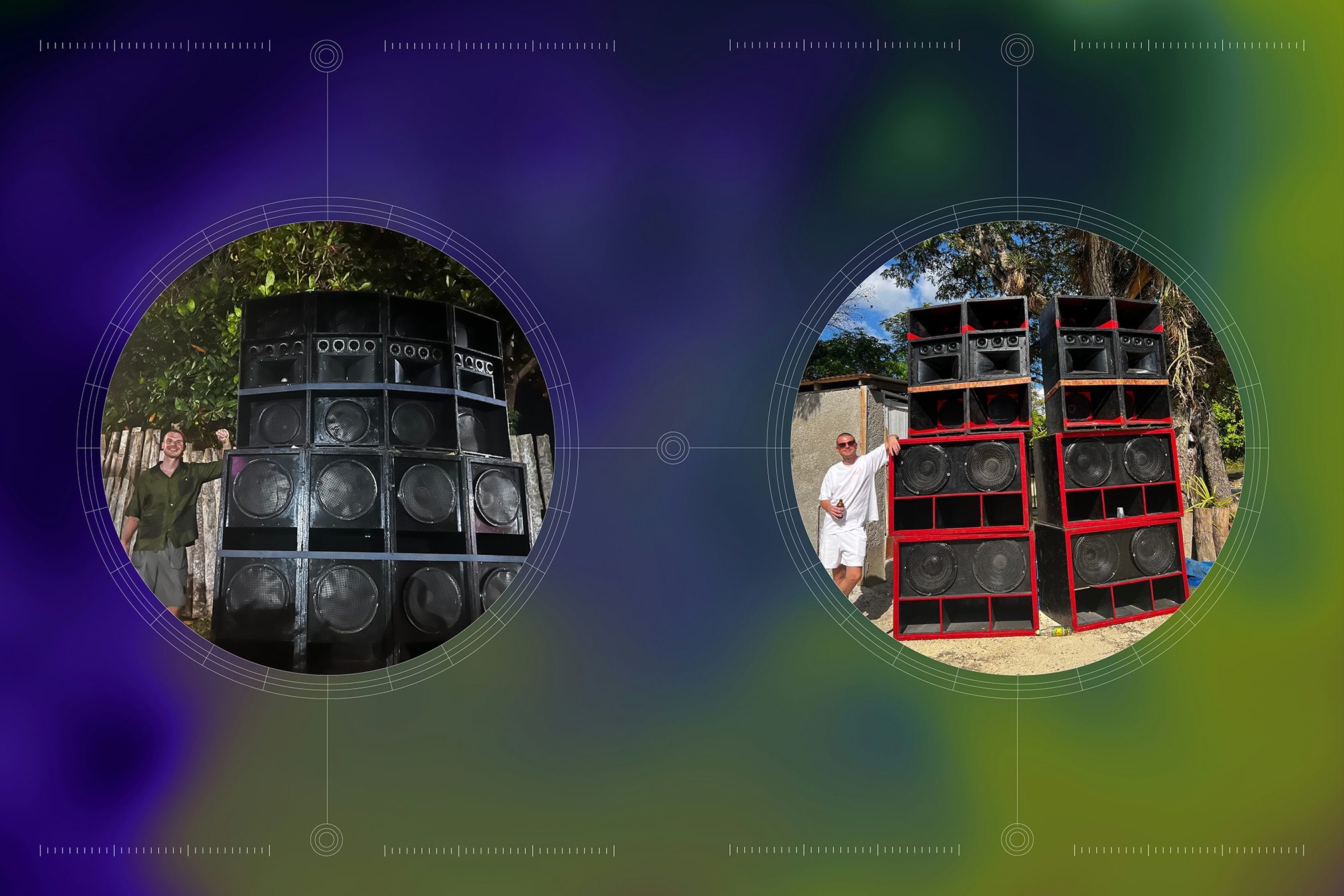

My psychology was improving but I still missed the physical feeling of live music. I’d take tentative steps back into the world of loud music – life events like weddings and birthdays – but my tinnitus got louder after each one, due to the damage in my inner ear. I remained incredibly cautious during this time but decided to take a risk on checking out some music in an outdoor setting, taking my ear plugs and a crew of friends to an all-dayer in London in the summer of 2018. We became the “back left” gang and, for the first time in two years, I was with my mates dancing in the sun. I have vivid memories of feeling bass in my chest during Princess Nokia, rolling around in the grass in glee and soaking up Larry Heard’s iconic Chicago basslines.

I got cocky and decided to check out Notting Hill Carnival, traditionally one of my favourite weekends of the year. I wore earplugs but I woke up the next day with a type of raging tinnitus that definitely wasn’t there before. I had many moments like this, wondering “is it louder than before?”, while experimenting with different settings and situations. It was laborious and, at the time, felt like an eternity of missed gigs and epic nights out, as well as a growing distance from the epicentre of music culture.

In 2019 I finally decided that my tinnitus couldn’t get any worse and that my weapons of choice – the silver or black filters in my ACS in my left ear and a solid ‘blocker’ in my damaged right ear – would help me enter most nightclubs in London, where volume isn’t always at a premium. I placed my bets on going to see SHERELLE play, a DJ I’m hugely inspired by and an artist I was willing to risk my ears for. I had amazing nights seeing her and 6 Figure Gang at Colours in Hoxton as well as her headline show at Electric Brixton, standing at a safe distance at the back of the venue with a mate. I was becoming free again.

For years I yearned to get back to running nights, DJing and contributing directly to The Culture. I started to have dreams where I was promoting Tropical Waste back at The Waiting Room, this basement in North London where I threw some mad little parties. I’m thankful for the time away from nightlife, the whole experience made me more resilient and forced me to explore other avenues of life, but I couldn’t ever find anything that beat the rush of being stood in front of a soundsystem. It’s been a journey but I’m happily pitching in again, running raves, reviewing music and checking out all these amazing venues and DJs that were just out of reach for so long.

I know people in music – other DJs, journalists and industry folk – with more extreme types of hearing loss than me or who were born with deafness or who go through bouts of debilitating tinnitus and I am acutely aware and grateful that I can still hear through my left ear and that the rest of my mind and body is functioning and healthy. One of the coping mechanisms that I have for dealing with my tinnitus – which rages in my right ear constantly – is to tell myself that I’m still alive and that I’m still here. I have immense gratitude every time I experience live music because at one point, I thought I’d never be able to step into a nightclub or venue again.

I wanted to share my experience because we don’t talk about the physical and psychological effects of hearing loss and tinnitus enough in the music industry (or even how essential it is to wear ear plugs around loud music). People suffer in silence, perhaps because they don’t think that anyone else is going through the same thing as them or because they don’t consider their condition to be a ‘proper’ illness or injury. It’s certainly not noticeable to the outside world and it’s a very specific type of trauma. If you’re reading this and you can hear that ringing – don’t worry, you’re not alone.

Find out more about Tinnitus Awareness Week 2024 here

Seb Wheeler is a digital strategist, music & digital media writer, DJ and curator. Follow him on Instagram