Features

Features

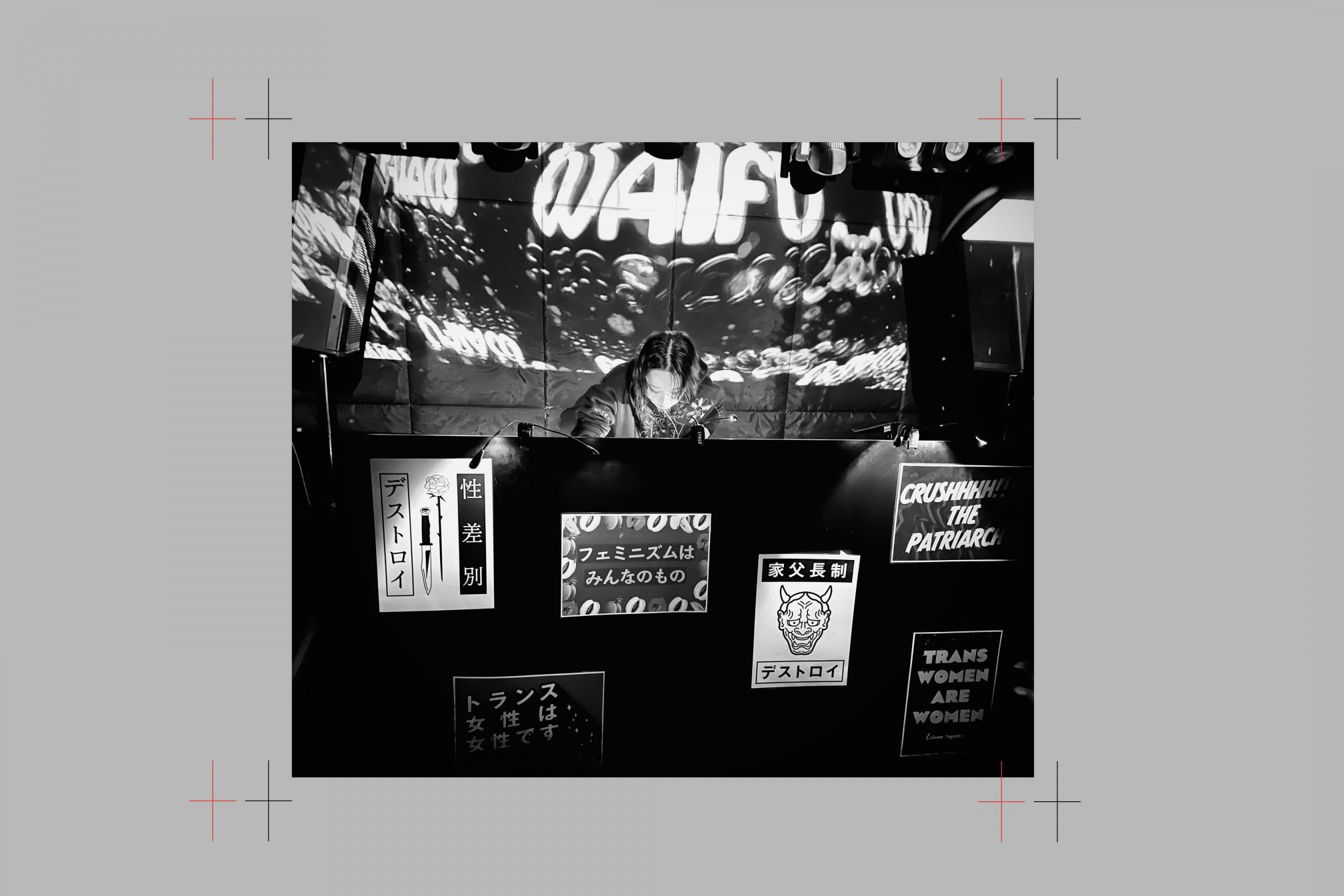

"Genuinely needed": How WAIFU is revolutionising Tokyo's queer nightlife

Founded as a response against discrimination, queer and femme collective WAIFU is bridging the gap between music and politics in Japan, pioneering a focus on inclusivity, accessibility and activism in the club scene and beyond

Functions is our interview series profiling parties from across the world. Next up is Tokyo's WAIFU

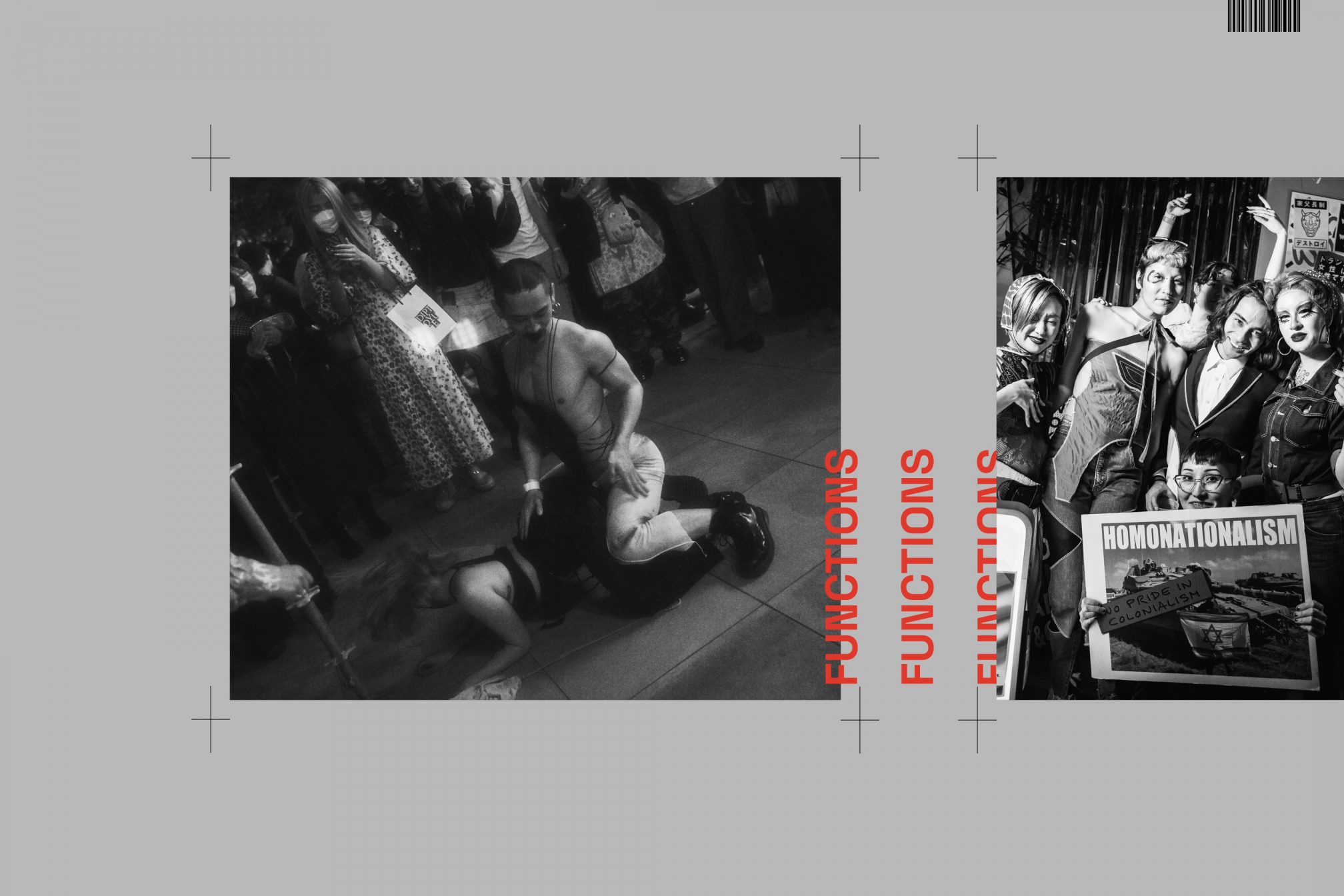

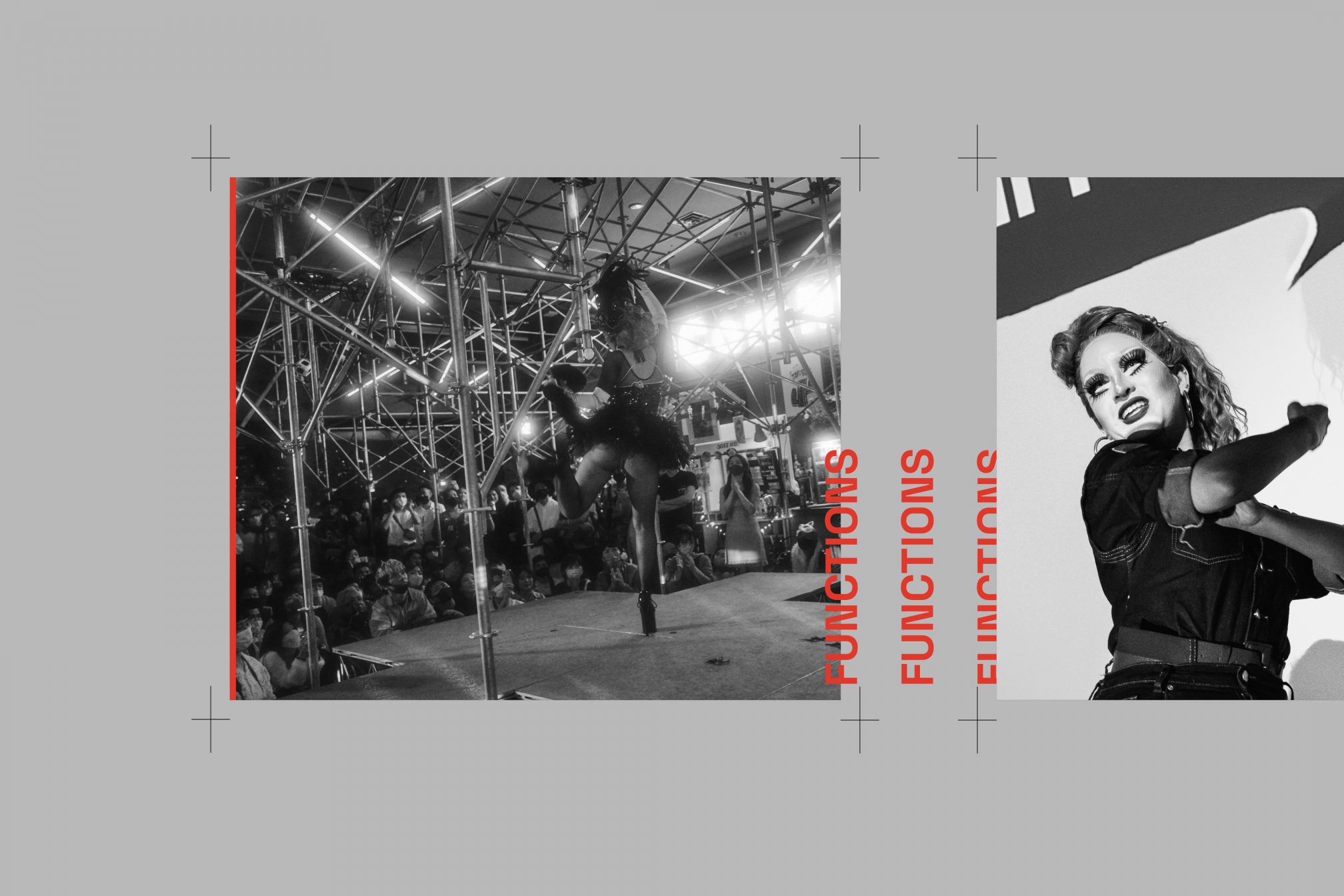

Before WAIFU came along, the Tokyo queer scene was almost devoid of two crucial components: inclusivity and decent music. But WAIFU has changed that. The seminal queer and femme collective released the Japanese capital’s LGBTQI+ scene from the shackles of Ni-chōme (Tokyo's gay district) back in 2019 and hasn’t looked back. It’s known for open-minded, inclusive parties that can encompass anything from zine fairs and drag queens to bondage and hard techno.

WAIFU began as a response to an incident which happened in Ni-chome, when member Elin was denied entry to a lesbian party for being a trans woman. Being turned away led the people present to form their own “counter-party,” held just 10 days later at Tokyo venue Aoyama Hachi. A novel idea in Tokyo at the time, the “counter-party” designed an anti-harassment policy, sold zines promoting activism, and had a chill out space. The event was supposed to be a one-off, but it went so well that co-founder Asami told us “the venue asked us back for a regular event. We ended up holding six editions there.”

Read this next: 8 up-and-coming Japanese DJs that you need to know

Since its inaugural event, the collective has booked DJs ranging from regular guests Sapphire Slows and Mari Sakurai to New York-based Haruka Salt. WAIFU has also branched out, hosting talks at PARCO’s DOMMUNE streaming site and running an ongoing radio show on New York’s The Lot Radio.

The group has also inspired many local partygoers to launch their own inclusive events, boosting queer representation in Tokyo’s promoter scene. We spoke to three of its members: Elin McCready, Maiko Asami and Midori Morita, who shared the thinking behind the collective.

How did you start WAIFU? And why is it called “WAIFU”?

Elin: After the [denied entry] thing happened, everyone involved walked down the street to a convenience store and got a drink. We were standing in some parking lot, everyone sad and looking down kinda .. then we started talking and someone was like “why don’t we have our own space anyway? Let’s start our own party!” It might have been Dora Diamant, who stood up for me in the original incident and who we owe so much. I went home and said this to Midori and she was fired up and found us a space. We did the first WAIFU nine days later.

We weren’t sure what to call it. Lisa Tanimura, who was involved at the beginning, proposed that name with the idea of reclaiming it (or just claiming it) from the specific otaku subculture that uses it for their favorite anime girl; there is a misogynistic vibe there, at least in many cases, that we wanted to push against.

Asami: In the beginning, when the group first got together to talk properly at an izakaya, members were from a mix of countries including Japanese, English and French-speaking, so we didn’t want to use a name tied to one specific language. “WAIFU” is a slang word that traverses various languages. Another reason is that we wanted to show support for Elin and Midori, who were in the middle of a lawsuit against the Japanese government at the time, petitioning them to allow Elin’s gender change on all her documents; and in turn to recognise her same-sex marriage to Midori as “婦婦(wife & wife).”

Read this next: What to do if you get sexually harassed in a nightclub

How do you uphold these values at your events?

Elin: We don’t have a door policy that excludes people. It doesn’t seem to us that there’s any kind of line that can be drawn that lets in only the people that should be there and keeps out all the people who shouldn’t (in terms of how they act), whether a line of gender, sexuality, or whatever. The people you want in a party are people who are open to all kinds of other people and who aren’t going to be assholes. Then if it turns out someone is an asshole you can throw them out. In practice, we ask people to agree to a statement of values at the door. We’ve never had anyone refuse to follow those guidelines, and consequently haven’t had to turn anyone away. I think the phrasing on the flyers and the statement on the site itself functions as something of a self-selection mechanism. People who want to be disasters don’t show up.

Asami: On flyers and at the venue we have the policy clearly posted, and we’ve tried some other initiatives too. In May 2019, the same time WAIFU started, there was a groping incident in a large club in Shibuya, which became a bigger issue as the security staff didn’t try to help the victim. We realised that we couldn’t rely on the club’s staff to respond [to instances of sexual harassment] so we got clubbers who agreed with our policy to help. We wrote “SECURITY” on stickers, and gave them out so guests could wear them where they were visible. This helps to make participants themselves actively aware of the cause and creates a safer environment, sending out the message that we’re all looking out for each other.

We also implemented an idea suggested on one of the forms that we sent out regarding sexual harassment in clubs. To help organisers sort out any potential issues as soon as possible, we put up dedicated posters which contain a QR code, and when you scan the code, it takes you to a form where you can anonymously (or otherwise) report sexual harassment. I think that, even in large clubs or clubs with blind spots, the idea that you will be reported as soon as anything happens can act as a deterrent.

When WAIFU first began, it was a pretty new concept for Japan: a queer club event outside of Ni-chōme, open to everyone, with electronic music, DJs and people from a range of backgrounds. How did people react?

Elin: Some people were extremely happy. A lot of people didn’t feel comfortable in either existing club spaces, because they were excessively cisheteronormative and also frequently had a lot of harassment, and some because there just weren’t spaces for queer people (though there were for cis gay people, particularly men). I remember someone coming up to me at one of the early parties and thanking me for having started the space, literally in tears. It is really amazing to feel that the thing you are doing turns out to be something that’s so genuinely needed.

There were some negative reactions though: one thing I found funny and also sort of insulting and shocking was the rumour spread by some terf-y people online that the whole thing was planned, that we had set up the whole party and then I deliberately went down to start a riot at the women-only party for publicity. Um. No. Some people still spread this rumour! But in the end it’s a compliment: we took it to mean that they just couldn’t believe that we were able to set something up so quickly that took such root in the community.

Asami: At the time, there was no crossover between nightlife culture and activism and social issues such as feminism. There were study groups and book clubs, but there was no meeting point. I actually met Elin at one of these groups, and we bonded over our love of nightlife - I was organising a queer party and Elin likes going out. I’d been hoping for a non-academic, grassroots space or scene in Tokyo, so I'm super happy with what we’ve been able to achieve with WAIFU, and other people have told me the same.

In Tokyo around 2018, a wave of anti-trans sentiment had started on social media, after Ochanomizu Women's University announced it would accept trans women. The year after, when Elin posted about the incident in Ni-chōme, there was a huge response. Some were negative, but many others from varying backgrounds, and different types of activism including feminists, anti-racism, and so on supported and stuck up for her. When we held the first WAIFU (we call that one the “counter-party”), the activists who’d been supporting and had consequently helped promote the party came along. We all hung out, listened to music, chatted and socialised together.

Read this next: How DJ activism can actually make a difference in real life

How do you go about booking DJs? You have quite a varied roster of residents, how do you timetable everyone effectively?

Midori: Our only DJ member is Chloé Juliette, so she DJs as a resident at most of our parties. Some other DJs we’ve booked include cis gay men, DJs with disabilities, and young DJs with little experience. As you can probably guess, some of them haven’t had much chance to perform and they need more time and space to sharpen their skillset, so we have them play short sets or the opening slot and so on. Essentially, we actively book this type of DJ because we think it’s important to create opportunities for them. The other DJs who’ve performed tend to be cisgender women who align with the WAIFU policy, and although not as many people yet as we would like, we’ve also booked trans DJs and non-binary femmes. We have an ongoing chat group with the other party — SLICK — that me and Elin run alongside popular local DJs Mari Sakurai and 7e, and in that we are always recommending DJs we’ve found.

My theory is that “Good organisers and good DJs go out.” I go out at least weekly and often discover new DJs then. I don’t think you can organise the hottest party if you stop going out yourself.

WAIFU began at Aoyama Hachi, but you’ve moved around a bit, recently hosting a party at Commune, for example. Why is this?

Midori: Hachi had been shut down not long before the first party by the revised Adult Entertainment Business Law (previously called the “No Dancing Law”), and it made a lot of sense to host our counter-party there. I think if it was accessible then we’d definitely still be holding parties there.

Elin: Hachi is a wonderful space, but it is a little special in its layout: it is on three floors, each of which is a single smallish room. The floors are connected only by narrow stairs. It is one of the least accessible spaces I’ve ever been in. We want WAIFU to be a space that is open to everyone and we are working toward this as best we can; Commune is completely accessible – it has an elevator and all the parts of the venue are friendly to wheelchairs – so we have done some events there.

Asami: At the moment, WAIFU doesn’t have a base per se. The event at Commune was the first time we held a proper event at an accessible venue and I’d like to try other venues too. It depends on the event really. We recently started a WAIFU sessions mini-party, where we live-record the mix for our next radio show. Held on a weekday, it’s a place for queer folk to gather and just hang out. We actually held the first of these a couple of weeks ago, on a Tuesday at Shinjuku club, SPACE. It’s a super-tiny venue but it’s accessible and wheelchair users have given us good feedback.

Read this next: Nightclubs need to be way more accessible for disabled clubbers

WAIFU is not simply a club night, you also host talks at DOMMUNE and are politically active on your social media accounts. How do you decide what to share and host? Can you explain your policy regarding this?

Asami: It’s hard to talk in clubs and sometimes sharing things through social media can become complicated, so hosting talks and workshops enables us to relay a message and have an open dialogue in real time.

In terms of how we pick the themes, it’s always something topical. When the incident happened with Elin, it was a big deal across social media; sites both international and domestic, such as Pink News and BuzzFeed picked it up. Around the same time, trans discrimination had become a huge issue, and the aforementioned groping incident had happened at the club in Shibuya. So, just two months after the first WAIFU event, we held our first talk at DOMMUNE, covering both the trans discrimination and sexual harassment issues and how they are connected. There was a great response to the first talk event, as we had people from lots of different demographics including queer, clubbers, and activists. Since then, we’ve held a talk series “WAIFU @ DOMMUNE” four times.

We also listen to feedback from our audience and react to that. Promoting our club-focussed anti-sexual harassment policy, for instance. People told us that the club is a place where sexual harassment happens anyway, so it’s the fault of the victim for going in the first place. In order to change that perception, we held a lecture series on clubbing history with guest speakers, to make more people aware of the fact that the club was originally intended as a safer space for racial and sexual minorities.

Our policy regarding social media is generally to share as much as we can on a daily basis, as long as it aligns with our policies. These include issues related to minorities, like gender and racism as well as announcements of protests, calls for signatures/donations and so on.

Even for people who just come to dance, I really hope that having content like signable petitions will get people interested in social issues, and maybe start to engage in activism themselves.

I think WAIFU’s activism is especially striking in Japan, a country where music and politics are seen as completely separate entities.

Read this next: Politics and dance music are intertwined and there's nothing you can do about it

What are the reactions to your social activism like from local clubbers?

Asami: While I get the impression that in the mainstream scene music and politics remain completely separate, in the local underground club scene — especially among those who come to WAIFU — when we post about politics and so on there is an overwhelmingly positive reception. When people come to the parties, they’ll chat politics, and people come up to me to let me know what they think about an issue we’ve posted about. I’ll meet someone on the dancefloor one weekend, at a demo the next, and vice versa.

Elin: I also quite often have the experience of being approached personally in various spaces and having people express their appreciation for the political work we’re doing. Some of these people are clubbers and some aren’t, but the number of club people who think about political issues is growing quickly, and I am happy that WAIFU has been able to contribute to that.

WAIFU started just before COVID, and as the world has reopened, there has also been an increase in other queer-friendly parties around Tokyo. How has the Tokyo scene changed since WAIFU began?

Asami: A bit before WAIFU began, there were incidents of racism and sexual harassment in the club scene which weren’t really spoken about on social media, but a small number of people around the victims had started to notice the situation. We were very aware of the intersectionality of discrimination and put up our own statements in clubs. Then, when Elin posted about the incident of being discriminated against as a trans woman, this problem, which had been dismissed as “typical Ni-chōme” before, became a clear LGBT discrimination issue that people couldn’t ignore. It feels that since then, people have changed not only in the club scene but also in the LGBTQIA+ scene as well.

During COVID, WAIFU parties were reduced to once or twice a year, but in the meantime SLICK began with its own statement, and since then I feel that the growth of parties with an active anti-harassment policy hasn’t stopped.

Elin: We hosted a New Year's party a few years ago during COVID. Everything was booked, set up and paid for; but then case counts went up again and things started to close. Japan never had a lockdown though and lots of the big (straight) clubs with shit music were running full-on throughout the whole thing. We thought hard about cancelling the event but ultimately decided to do it, for three reasons: case counts were still low, people were having problems with isolation and depression, and many club people had lost work during the pandemic, so we wanted to help get people some money. We took all the precautions we could.

I’m bringing this up because we got a lot of criticism of the form “How can you do this as a queer party?” We thought: The straights have been throwing giant parties at their trash clubs through the whole pandemic. Why can’t we do a party too? Why do we have to be “better”? I found it quite interesting how queerness is sometimes equated with moral value and the elimination of risk. I think this incident reflected the kind of puritanism sometimes seen in the current queer scene, which I think is not a good development.

Read this next: Queer the dancefloor: How electronic music evolved by re-embracing its radical roots

How has WAIFU changed since it began? Any learnings?

Elin: A lot of things have changed. We have started to focus much more on accessibility which has caused us to move to use only venues that are wheelchair-accessible. We also fielded a very wide range of complaints from attendees. WAIFU occupies a slightly difficult space in that it’s both a club event and also one of the very few queer spaces in this very large city, so it gets a mix of clubbers and people who just need a space, who are often not that familiar with club culture. It’s been a challenge negotiating issues like the need for non-smoking spaces and different attitudes toward approaching people in the party and starting a conversation, which some people turn out to view as harassment in and of itself.

For me, I think all this is good: it helps us learn about each other, what other people need, and requires us to think as a community about what’s acceptable and what isn’t. These kinds of conversations are one way to address the problem of puritanism I mentioned just above.

What has been/is a challenge for WAIFU?

Midori: For me, it’s finding a venue. Searching in Tokyo for somewhere that’s: accessible, with designated smoking and non-smoking areas, where we can hold a pop-up store, have a chill-out space, that isn’t too big or too small, where we can make a profit and the sound is good is a really tough job.

Asami: As well as what Midori said, another thing for me is striking the balance between creating a space that is open to all with an open mind and being inclusive, maintaining its queer-centricness, keeping its artistic credibility and being a place for activism. It’s challenging but as no one in Tokyo has done this before, I think it’s incredibly rewarding.

Please share a memorable WAIFU moment?

Midori: It has to be the first one. I was super happy because we did everything at such short notice yet so many cool, queer people made it down. It was the first and last WAIFU for Dora Diamant, who was the inspiration for the party, and who passed from cancer just one year after.

Asami: I have very vivid memories of the memorial service we held for Dora at DOMMUNE during COVID. She passed away suddenly before we got to know her well so we weren’t able to share anything with her in person. It was frustrating and so sad that she couldn’t hear about the new developments in the Tokyo scene, which had happened thanks to the counter-party she helped to start. We expressed all our feelings, including the gratitude that she spoke up against discrimination, through a talk and performances.

At the time, as well as the memorial talk, we hosted the one about accessibility for wheelchair users in the club scene. The owner of DOMMUNE, Naohiro Ukawa, listened to the talk and afterwards, as DOMMUNE is a wheelchair-accessible venue, he said he’d let all people with a physical disability certificate in for free from then on, as they were excluded from many aspects of underground club culture due to inaccessible venues. Keita Tokunaga, a DJ and wheelchair user, closed the program by saying “Ukawa-san is Dora to me.” I still remember that moment. [Laughs]

What does the future hold for WAIFU?

Midori: As we have been and always will be, we want to keep our minds open, as we look towards the future and move in a way that we believe to be “right".

Kim Kahan is a freelance writer, check out their website