Features

Features

WipEout: The story of the world's first rave-inspired video game

Inspired by dance music, living room after parties, and futuristic design, wipE′out″ changed the perception of video games forever. Speaking to the people who made it, Daniel Dylan Wray delves into its legacy

In 1993 Nick Burcombe was sitting at home playing Mario Kart on the Super Nintendo. A few beers down, he was locked deep into a session desperately trying to win the 150cc championship. “I kept getting my ass handed to me on the final lap,” he recalls. The game’s music, which changes to double-tempo on the final lap to increase pressure, was beginning to drive him mad. So he started to play his own records.

This time when he got to the final lap of the championship, it coincided with Age of Love’s 1990 self-titled track – a hypnotic piece of pulsing yet melodic trance –pumping out the stereo. “Then something extraordinarily weird happened,” he recalls. “I entered a trance-like state which felt like an out-of-body experience; one not dissimilar to the substance-induced experiences I’d had at many Blackburn raves.”

Burcombe suddenly entered beast mode in the game. “I absolutely nailed the 150cc Championship on my first attempt with this track playing,” he says. “Winning by quite a margin.” In that moment of elation and hyperfocus, something had gone off in Burcombe’s brain – a lightbulb moment, albeit one that flashed with strobe-like intensity. “It was the best gaming experience I’d ever had,” he says. “That moment etched itself into my brain and I wanted everyone to feel that too.”

Within a couple of years, they would. Via a new anti-gravity racing game complete with its own pioneering trance-techno soundtrack. WipEout, released in 1995, was to be the world’s first rave-inspired computer game.

Burcombe was working as Lead Designer at the Liverpool game studio Psygnosis and the company had been bought by Sony to create new games for the launch of the Playstation One. Psygnosis artist, Jim Bowers, had already started work on a very early concept demo movie for a futuristic racer game when he went down the pub with Burcombe one night. “Relaying the story to Jim about my trance Mario Kart experience, he also started to get excited,” recalls Burcombe. “So we decided to put new music to his video. We opted for The Prodigy’s ‘No Good’ because of the pace of it really fitting with the action on screen.”

Another lightbulb moment began to ping and shatter inside people’s heads once they saw this marriage. “There was a shift inside the company,” says Burcombe. “Everyone understood it on a conceptual level. From that point on, we knew we needed a great soundtrack in the game. It became part of the identity and a core element of everything we were wanting to make.”

So they went to their in-house sound designer, Tim Wright. “Nick blathered out the names of bands he was listening to and they just went straight over my head,” says Wright. “I just nodded.” While Burcombe was a hardcore raver and dance head, Wright was not. “I was a lover of old school stuff like Vangelis and Jean-Michel Jarre,” he says. “So suddenly I was confronted with music that was coming out of the acid house era and into trance and techno vibes.”

He did his research but it left him somewhat cold. “I got a stack of Ninja Tune CDs but it was all a bit dry,” he says. “A lot of it was just filter sweeps and drops and then rises again. I was like, where's the actual music? I really didn't get it.”

Wright’s own epiphany came when he went clubbing with his Psygnosis workmates, who were frequent visitors to thumping underground club nights like Voodoo in Liverpool’s Le Bateau. “The last time I'd done nightclubs was when Stringfellows was big,” laughs Wright. “It took me a little while but I was like, I get it, because it's not about listening to music, it was about feeling the music.”

Read this next: How Blackburn dominated warehouse raves in the Summer Of Love

And so Wright took his newfound connection to feeling the pulse, throb and hypnosis of dance music back to his studio. “But as I'm writing it, I'm shitting myself because it's like oh by the way we're also getting The Chemical Brothers, Leftfield and Orbital to feature [on the soundtrack] in the game,” he recalls. “You know, these artists who have been doing it for years in this style that you've only just discovered and previously were either ambivalent about or kind of hated.”

He came up with a moniker for making this music, CoLD SToRAGE, and within weeks had crafted a soundtrack of high BPM trance-techno that was both melodic and glitchy, hard-edged yet immersive. A year or so later this music was being funnelled, and indelibly left, into the minds of millions of gamers and clubbers. Recent Mixmag cover star, Evian Christ, being one perfect example of an artist who has spoken of the significant role that WipEout has had in instilling his love for trance and setting him off on his own musical journey

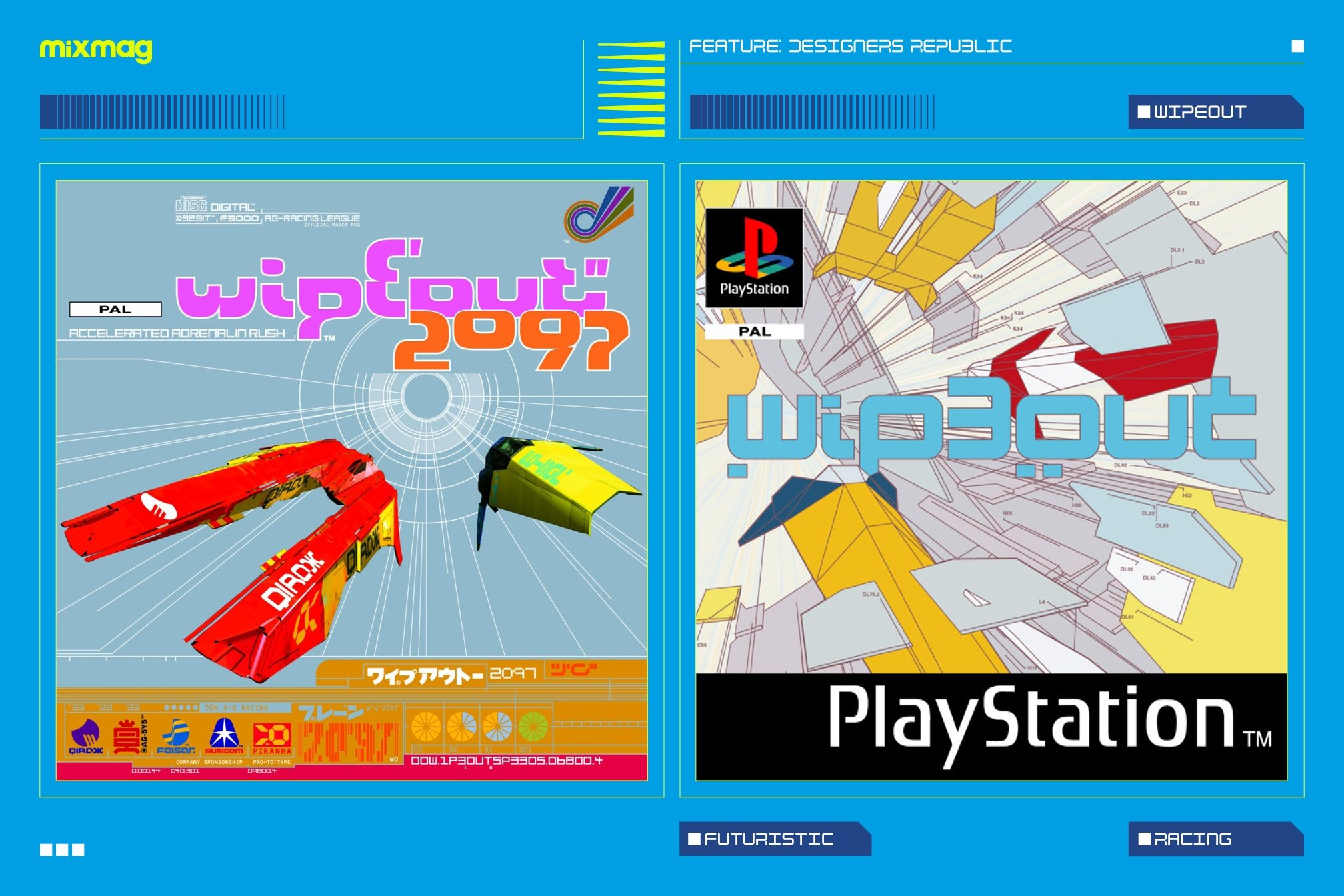

But Psygnosis’ desire to capture the spirit and energy of dance music into a video game went way beyond just a zeitgeist soundtrack. The whole project underwent an accompanying aesthetic overhaul. They brought in The Designers Republic, a Sheffield-based company who were responsible for the design and visual output of Warp Records. “Designers Republic was the coolest graphic design house in the country,” says Burcombe.

Ian Anderson from The Designers Republic recalls Burcombe’s vision when they spoke: “It was more techno sci-fi than the then-standard metal-soundtracked Dungeons & Dragons, Warhammer type imagery. We saw the whole WipEout thing as a potential playground for us to explore all the futureworld branding ideas we didn't have the clients to use them for in the real world. We didn't want to design the game, we wanted to create the world in which it existed.”

After they agreed to come on board, one day a fax came juddering and squawking through from Psygnosis to Designers Republic. It was their confirmed brief: “Change the way computer games look forever.”

Damon Fairclough was working at Psygnosis as a creative writer for the game and remembers it all feeling like a turning point. “This all felt really different to where games had been up to that point,” he says. “Prior to this, all the packaging at Psygnosis was done by Roger Dean [illustrator known for doing artwork for bands such as Yes] so they had this old, prog rock fantasy look. It couldn't have been more outdated. So this idea of packaging it more like a record – it all felt so new.”

The reputation attached to gaming was significantly different back then. While we now live in an era of professional Esports where gamers are lionised multi-millionaires, in the mid-90s gaming carried a less desirable image. “If I told people I was working at a games company, the picture they had in mind wasn't cool,” says Fairclough. “It wasn’t a clubby, fashionable, elite design kind of image they had in mind. It was grungy teenagers in their bedrooms with the curtains drawn.”

Wright echoes this sentiment. “The target audience they decided on wasn't bedroom gamers anymore,” he says “They wanted people coming back from the nightclubs or on the Sunday morning after the club. To be something that would be in the living room and be a shared experience, rather than a solo thing.”

Read this next: Video games are influencing a generation of electronic innovators

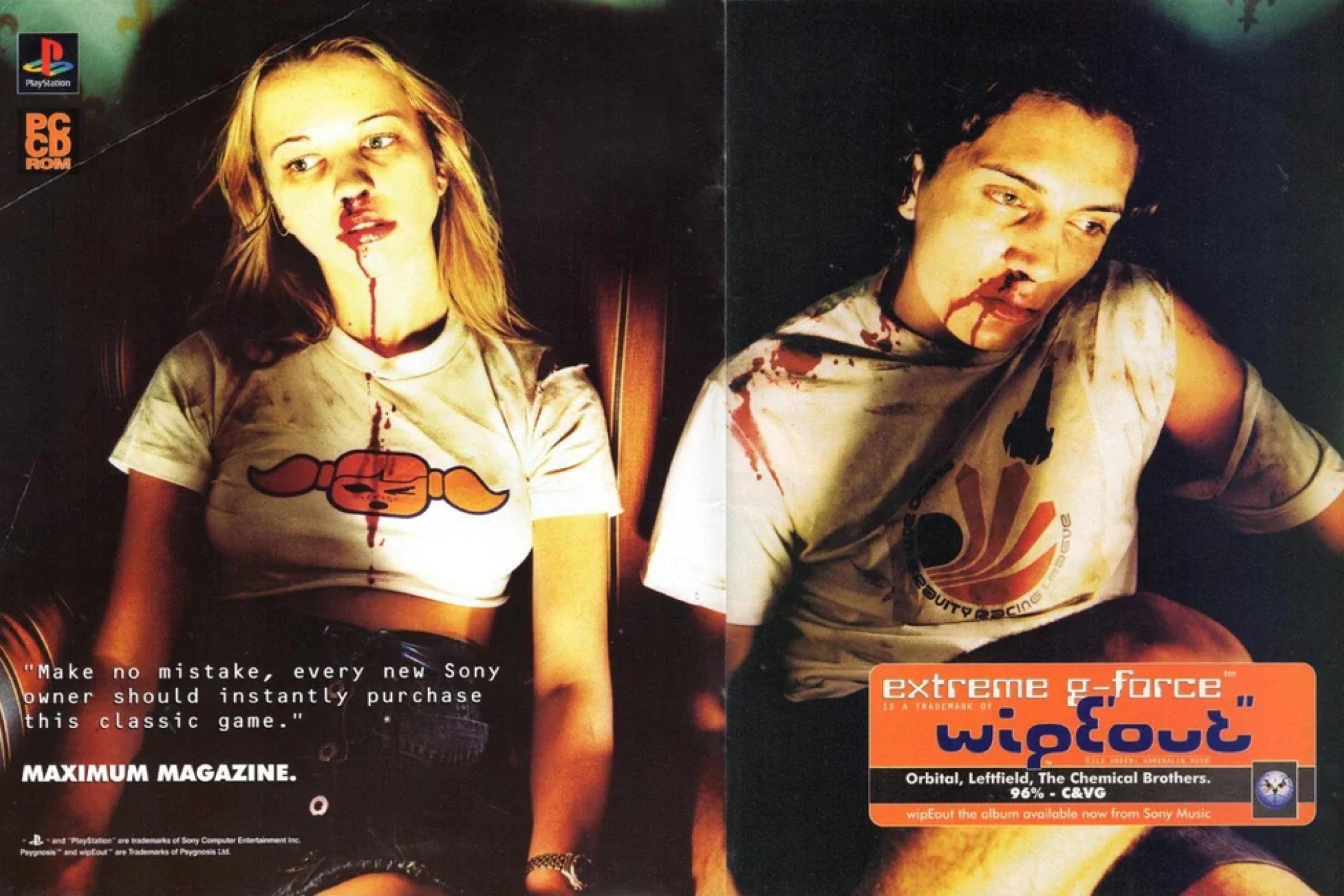

The marketing for the game involved an advert of two young people - one of whom was a pre-fame Sara Cox - looking dishevelled, wiped out, and with blood streaming from their noses. It caused controversy, with The Sun, in typical fashion, dialling up the outrage because the game had an all ages certificate – so they ran with the story of it being a game aimed at children that was glamorising drug use.

“I look back on it now and obviously people are going to see it as a drug reference,” reflects Fairclough. “But that wasn't what we were talking about. It was to do with the speed of the game. In the initial notion of the visuals it was quite a modest little nosebleed but the guy doing the makeup went to town more than we were expecting.” Fairclough recalls “the shit hitting the fan” with big bosses at Sony who saw the ad in print for the first time.

Throw in the fact that the game’s name was stylised with a notably protruding E and you have another accusation of drugs and rave culture infecting and corrupting children. “It was purely a typographic structure,” explains Anderson. “But having the moral moronity kicking off about secret messages to pervert our children and society was the kind of gold dust that we could never have imagined.” The furore around the game, of course, only added to its edgy appeal.

In yet another strange, yet prescient, moment of symbiosis, Red Bull was also thrown into the mix. The nascent energy drink was introduced to the UK in 1994 and a deal was done for it to be an in-game sponsor. Today, it’s hard to imagine a world in which the drink is not an inescapable presence in the world of dance music, but back then it was an unknown entity as it stepped into this hybrid mutation of dance music and gaming. People had no clue what it even was. “I remember conversations along the lines of ‘apparently if you mix it with vodka it's like taking half a pill’,” recalls Fairclough. Wright was similarly naive: “I drank six in a row and I was grinding my teeth and sliding up the walls. I nearly had a heart attack.”

An early version of the game demoed at an American games conference and blew minds. It was such hot property that that version was even featured in the cyber crime techno-thriller, Hackers, starring Angelina Jolie and Johnny Lee Miller. Upon launching with the PSOne in September 1995, the game was an immediate success. Not only the slick, super fast gameplay and sci-fi world it inhabited, but the music too. “I started to get fan mail,” laughs Wright. “And people were phoning the office saying, who's CoLD SToRAGE?” Before he knew it, Wright found himself being brought out live on stage with The Chemical Brothers. “It was surreal,” he reflects.

Read this next: The 9 best nightclubs in video games

The game that had been inspired by clubs also ended up in them. “Because Cream was still in its rapid ascendancy and it was local, it was easy to have conversations with them about putting machines in clubs,” Fairclough says. “Although looking back, it's hilarious because although it looked the part, the original was really quite a hard game, so you had all these absolutely twatted people trying to fly these machines and smashing into the side of the track.”

A follow up was quickly released in 1996, WipEout 2097, and this time the music element was pushed even harder. “The second one came along and this time the record labels were knocking on the door,” recalls Wright. Rob Manley is credited as A&R for the game. He was doing the same role at Virgin at the time, having signed the likes of The Chemical Brothers and The Future Sound of London. “I jumped on the train and went out to see them and basically unfolded the whole idea that we should really soundtrack the game, fully, contemporary style,” he recalls.

The resulting soundtrack even got its own standalone CD release as a compilation album. It featured The Chemical Brothers, Future Sound of London, Prodigy, Daft Punk, Photek, Underworld, Orbital, Fluke and Leftfield. “There was no blueprint for this at the time when it came to drawing up contracts for syncing music with video games,” Manley says. “We almost had to create the whole package from scratch.”

To give a sense of how far ahead of the curve WipEout was, huge titles such as FIFA – which has become synonymous with heavy soundtrack use – wouldn't start licensing tracks until FIFA 98. “It felt important,” says Manley. “It was a highly regarded collision of great music with a great game. Did some artists pick up a profile from the game? Absolutely, yes, because there's nothing more focused than listening to music while you're playing a game. You are so locked in.”

The game’s musical legacy is vast. “The number of people who have thanked me for starting their passion for dance music, their DJ careers, or starting to produce music, is amazing,” says Burcombe. “And gamers contacting me to describe their own trance-like states. It means we did a good job.”

At the end of 2023, Wright’s soundtrack as CoLD SToRAGE was released in a lush and expansive vinyl box set and it came loaded with remixes from artists such as Kode9 and μ-Ziq. There was a launch party where the likes of Plaid performed live, while Simo Cell, also a featured remixer, went b2b with CCL. “My main connection with that game is all about the music,” says Simo Cell. “I still spin some of those tunes in clubs today. It's pretty wild when you think about it — made for a '90s video game and still making people dance in 2023.”

Wright is blown away by its enduring influence: “If you go back to the sweaty 20-year-old sitting in the Psygnosis studio going ‘I'm out of my league, I don't know what I'm doing, oh my God, I'm gonna get sacked, what the hell do I do?’ and say ‘this is what happens’ … it's been massively unexpected and flattering.”

For the game’s co-creator, Burcombe, he feels it was a beautiful culmination of a point in time that led to a genuine paradigm shift. “WipEout’s lasting legacy was to help the games industry turn from what was almost exclusively a teenage nerdy boys market into something much bigger,” he says. “It ultimately changed the perception of gaming as an activity and I’m not sure that would have played out the same way if it wasn’t for its amazing soundtrack and graphic design. WipEout is more than the sum of the parts and rave culture helped gaming become cool.”

Daniel Dylan Wray is a freelance writer, follow him on Twitter