Scene reports

Scene reports

Pushing back: Women are dismantling the hardcore boys' club

The hardcore aesthetic is inspiring, informing and liberating a diverse generation of artists, yet the scene itself is still massively male-dominated

It’s midnight at Ground Zero, a time when most outdoor festivals in the Netherlands are winding down – but this one is just getting started. The huge swimming lake that by day attracts families to the site is just a dark glint in the background. Thousands of diehards have travelled from all over Europe to be here. There are kids decked out in Ground Zero merch, faces obscured by grimacing biker skull masks, and a whole peacock display of Australian-branded tracksuits: the uniform of the gabber devotee. The terror stage is at 250 BPM already.

Hidden in the trees is the unassuming Multigroove area, where Lady Dana is about to play. Dana van Dreven is one of the most important and longest-serving figures in hard dance. She started DJing at 18 back in the 90s and for a long time was the only female DJ in the Dutch scene. She’s worked hard over the decades to prove herself, headlining major events from Thunderdome to Tomorrowland and earning admiration from both the the hardcore and hardstyle scenes. In 2010 she was forced to retire due to health issues, but over the last few years has been slowly returning to form. This year has been her busiest since the comeback.

Van Dreven, dressed all in black, films the scene unfolding on her phone as ‘Hocus Pocus (Bow Chi Bow)’ by Vicious Delicious spins on the decks. The dancefloor is teeming with loveable freaks from hardcore’s embryonic days. There’s a 40-something guy in bermuda shorts and flip flops pogoing like a teenager, a rave smiley brandished across his chest. Elsewhere, a woman in a floor-length gown and golden butterfly wings and a group of female gabbers in Australians carve out a different set of shapes. Artists and Multigroove family commingle in the sidelines, and it all feels more like a backyard house party than a festival.

Read this next: "Techno purism can suck it": The return of gabber

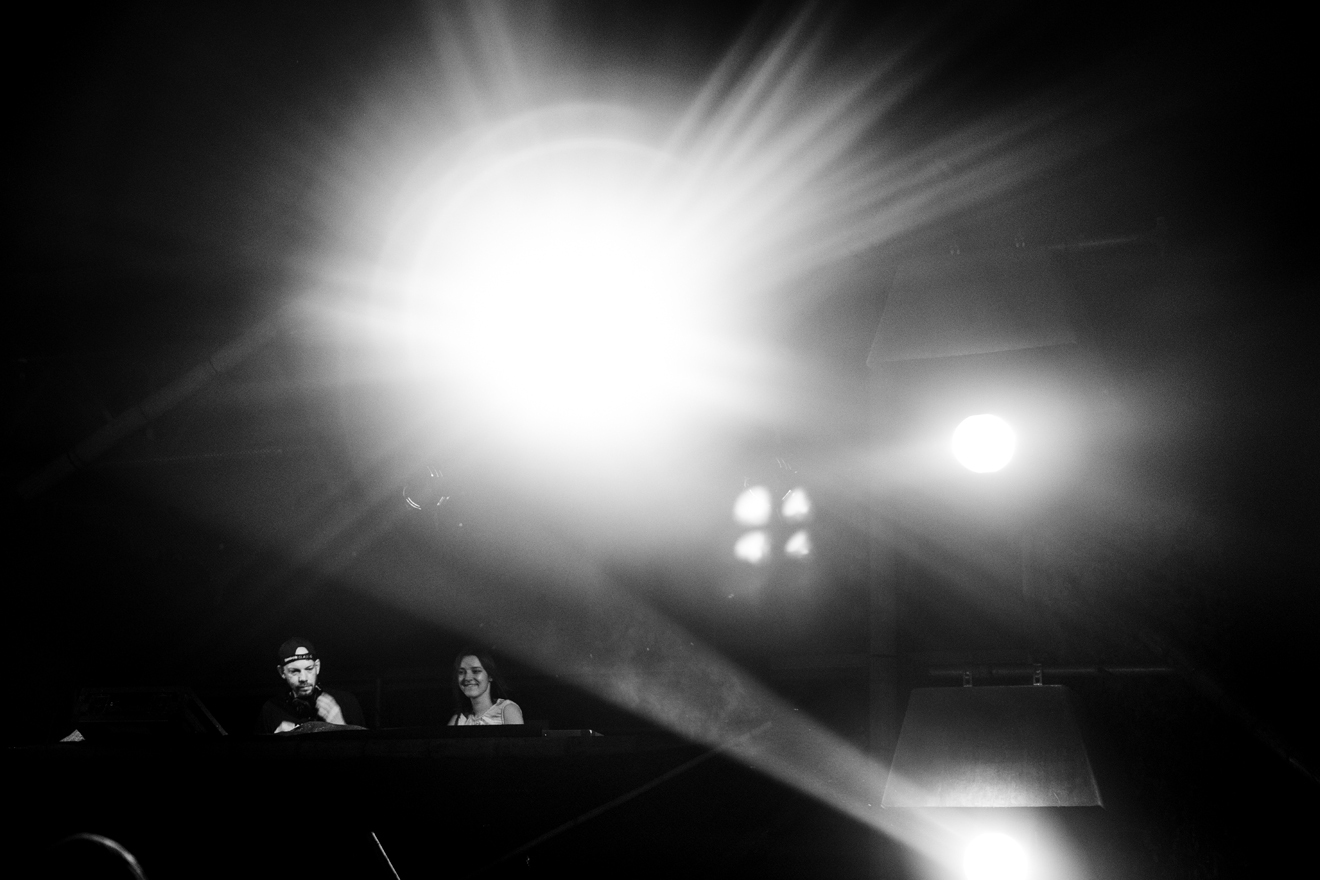

At the same time, over at the PRSPCT stage, Adamant Scream unleashes galloping hard techno from a jungle of camo nets. This is a new alias from Malin Kolbrink, who played more commercial music earlier, as Miss Hysteria, on the main stage. The Adamant Scream set is raw and dynamic by comparison: caustic hardcore smashing into drum ’n’ bass. As the selections intensify, so does Kolbrink’s ear-to-ear grin. She’s in her element.

Kolbrink, like van Dreven, learned to DJ as a teenager and has been involved in hardcore for almost 20 years. In 2001 she started performing as Miss Hysteria with her partner at the time, Lunatic, and has been playing solo under the moniker since 2014 (as Lucy Furr she’s also one of the very few female d’n’b DJ-producers in the Netherlands.) This is Kolbrink’s fourth time DJing as Adamant Scream, a project she launched with a four-track EP for PRSPCT earlier in the year, following one of the most difficult periods in her career.

“I didn’t feel connected to the scene, with my name, with anything,” she explains. “I really considered quitting because I make music to feel happy and healthy, and I wasn’t enjoying my sets. Now I’m going to produce whatever I want to produce, no boundaries, no borders.”

Read this next: 20 gabber rave photos that will make you want to party like it's 1999 BPM

Somniac One, another PRSPCT signee, played before Kolbrink. A producer first and foremost, she’s only been DJing for the last few years but has been honing her craft in the background for 14. As articulate, intelligent and approachable in person as her witty social media presence, she looks confident on stage now, though she admits performing was tough in the beginning. She’s never been a fan of the limelight.

Somniac One’s productions are technically outstanding and thoughtfully constructed. They’re not just club bombs – though they all rip up the dancefloor. Take her ‘Troubled Youth’ EP, which features the track ‘Shirtless’. It holds a mirror up to hardcore’s bro culture, with a wink. The artwork is a carefully constructed collage of women representing themselves on social media, wasted at parties or baring their flesh, with cutesy internet graphics obscuring their faces. The whole thing works as a subtle comment on the scene.

Hardcore is big business in the Netherlands, and part of a huge entertainment industry helmed by mega-brands like b2s and Q-Dance which put on huge spectacles like Defqon.1 and Decibel Outdoor. The stakes are high for artists in this commercial scene. It’s fiercely competitive, and the pressures to conform to industry trends – to sound a certain way, or look a certain way for women – are much more pronounced here. But Kolbrink has decided to retire the Miss Hysteria alias for good, and she couldn’t be happier.

Dutch hardcore has a more welcoming underground community, but you have to look harder to find it. PRSPCT is one of the most prominent underdogs in the scene, founded by heavily tattooed punk Gareth de Wijk, aka Thrasher. PRSPCT artists are family, individualism is encouraged, and women have significant roles in the organisation, both behind the scenes and on its roster. Artists like Kolbrink and Somniac One have been pushed out of the shadows and onto bigger stages at mainstream events because of PRSPCT.

Outside the Netherlands, hardcore appears to be experiencing a renaissance, but the context is important here. Boiler Room’s Hard Dance series, which launched at the start of the year, is attempting to archive this burgeoning nebula of 90s-born and internet-raised producers, DJs and collectives who are more interested in deconstructing and redefining hardcore than iconising it. This ‘new school’ reaches around the globe from Asia to Europe and includes artists as disparate as Meuko! Meuko! from Taipei, NON Worldwide’s Nkisi and Indonesian duo Gabber Modus Operandi, to idiosyncratic crews like Wixapol, Casual Gabberz and the female-led Drömfakulteten. Everyone in this scene is taking what they want from hardcore and doing something different with it.

Read this next: Get to know Nkisi, the artist uniting hyper-modern club sounds and afrocentric rhythms

Part of this new movement are multimedia artists like documenter, DJ and label owner Alberto Guerrini aka Gabber Eleganza, live performer and vocalist Astrid Gnosis and research-based visual artists Merle Vorwald, Tea Palmelund and Henrike Naumann from the 3ncore collective. All these people are exploring the subculture, politics and aesthetics of hardcore through a creative, critical lens. Combined with big-room techno stars like Nina Kraviz and Dax J bringing a more hardline approach to their DJ sets and label curation, together with media platforms showing a more general interest in the hard dance scene, hardcore has never had such a wide and receptive audience as now.

This new scene also appears to be more diverse and inclusive, with a growing queer community and a more conspicuous female presence. Not only are there more female artists (and a better balance of women to men) in the ‘new school’, there are also more women on the dancefloor and in the background producing, promoting parties, hosting radio shows and running labels.

Crew culture and collectivism is a significant tool for this new generation, where artists get ahead by supporting and encouraging one another. In the case of Drömfakulteten in Stockholm, this has resulted from working side by side for the last four years in the same studio space, a water-damaged, airless basement they’ve since had to vacate, where its 12 musically variegated members have learned their craft and grown together. “A lot of us would have stopped,” says founder Katja Lindeberg, who performs barbed sets with pointed shark teeth painted across her face as HAJ300. “We have really depended on being able to speak to each other and share experiences.”

Historically there have been very few women in hardcore; so few you could count them on your fingers. In the 90s when the scene was coalescing, there was Dana in the Netherlands, trans artist Liza ‘N’ Eliaz from Belgium, and the Michelson sisters Poka and Stella from French free party crew Fraktal. In North America there was hard techno producer and label owner Laura Grabb in Detroit and DJ Double D from Calgary’s first rave organisation, House of Unity Productions. Hardcore was a boys’ club, and in too many respects, it still is. According to Bianca Ludewig, hardcore scholar and member of the female:pressure network, this has translated into a lack of female role models which are needed to bring more women artists into the scene.

“There is this huge his-story and no her-story,” says Ludewig, who wrote her master thesis on hardcore and breakcore in Berlin (recently expanded and published by the cultural anthropology department of Vienna University). “Other scholars, like Tara Rodgers, have shown how women are getting systematically written out of music history, and as a woman you need some inspiration through role models to show that it’s normal as a woman to be a DJ or musician.”

Read this next: 20 women who shaped the history of dance music

Today there are more women in the scene, and some are hugely popular. Take Miss K8. Her 2018 track ‘Out Of The Frame’ was voted No 1 in the Masters Of Hardcore end of year polls, and she sells out stadium-sized venues when she plays. And yet, on festival line-ups women still represent a minority. According to a survey of 20 popular Dutch festivals made by VICE Netherlands in 2016, Defqon.1 and Decibel Outdoor had amongst the poorest male-to-female ratios when it came to acts billed. All-male line-ups are widely accepted, the argument being that there simply aren’t enough female artists around.

For Somniac One, hardcore’s lack of interest in gender parity isn’t necessarily a bad thing. “This way I can be sure I get booked for my music,” she says. “I definitely prefer it this way as I deeply care about my craft and I wish to be rewarded for this alone.” She’s a firm believer in meritocracy over quotas. “In my ideal world people should be rewarded precisely for what they do and the quality they bring.” Nevertheless, she admits to taking combative measures against being judged differently because of her gender, choosing a gender-neutral name and refraining from posting pictures of her herself on social media in the beginning.

“People have this certain image of you,” says Malin Kolbrink, who is petite and chatty. “I’ve always been told, ‘I didn’t expect this music from you’. Now I think, ‘Why the fuck not?’”. “I find people have a hard time associating women with hardness,” says art school-trained, London-based Astrid Gnosis, whose stylised videos, lyrics and confronting performances explore themes of chaos, violence and power structures, set to a brutal soundtrack. “I’ve been criticised for being too hard musically all my creative life, [told] that my looks were too aggressive, that my lyrics were too dark, that I look friendlier when I’m blonde, that I should make slower music.”

Just about every woman interviewed for this piece has a story about the scene – or the industry – that falls along the ‘everyday sexism’ spectrum, where they have felt undervalued at best, criticised and personally attacked at worst. Female producers are a particular target, especially online where their legitimacy is regularly called into question. It’s something Kolbrink, who has been releasing records for over a decade, has “had to learn to ignore.” The upside is that the die-hard community around these artists will often shout down the trolls on the artists’ behalf.

Read this next: Ghostwriters in the former USSR are turning Western DJs into stars

The culture of ghost producing in hardcore, which is ubiquitous amongst men and women, is a real disincentive to produce, says Kolbrink. “You have to have a certain will to do it [produce your own records] because it takes a lot of time, a lot of effort, a lot of money. Career-wise you have no advantage over other women who have ghost producers, other than creative satisfaction.”

In the commercial scene, the hardcore boys’ club has a darker side. With an overwhelmingly male fanbase (around 70/30 male/female) and a male-dominated infrastructure, mainstream hardcore tends to be marketed by and for men. This has produced some disturbing phenomena such as Rotterdam Terror Corps’ erotic dancers and their pornographic show, DJ Estasia’s glamour calendar, and a ‘sexy entertainment’ industry based on the objectification of women. But it’s important to note that hardcore artists and promoters ascribing to the ‘sex sells’ narrative are rare in a scene far more engaged in horror, science fiction and fantasy. For every bare breast there are many more monsters, skulls and ghoulish creatures. Nevertheless, the skulking misogyny and sexism in the scene is a real barrier to entry for women.

The challenge is to get more women involved in hardcore, as artists, as fans and as significant members of the hardcore infrastructure. For the Industrial Strength-signed Kilbourne in New York, better standards of care and security at events will help bring more women to the dancefloor. As a hardcore fan since high school, Ashe Kilbourne yearned to experience the Dutch hardcore spectacle after consuming hours and hours of YouTube videos of Defqon1 and Dominator. But when she finally made the transatlantic trip to visit both festivals in the summer of 2016, she didn’t always feel comfortable or safe.

“If you’re allowing people to display far right or fascist imagery, if you’re not intervening when guys are being really aggressive, to me that’s a huge barrier to women participating in the scene,” says Kilbourne, who delivers her fiercely held beliefs in soft tones. “If parties were willing to more dramatically interrogate a code of conduct for events, that, to me, could be huge.”

Read this next: 10 things you can do to make dance music less sexist

Spinoff Gabber in New York does this. It’s an event with a strict safe space policy that launched in 2016 with a Rotterdam Tunnel Of Terror-inspired ‘ravette’ at a secret location in Brooklyn, and promotes inclusivity and diversity at every level of production. Taking complete curatorial control over warehouse spaces allows Spinoff Gabber to make their audience, who are mostly queer, feel welcome. “To engage with this crowd, we have to make them understand that they will not only be literally safe, but free to make these spaces into something collective, communal, and authentically for and by themselves,” they tell us.

Something similar is happening in Amsterdam with Strange Days, a smaller scale event series and soon-to-be record label by DJ production duo Know V.A. Previous parties hosted Shanghai collective Genome 6.66 Mbp for their Netherlands debut and transformed a former squat venue into an immersive hard dance club night and exhibition space. Strange Days and Spinoff Gabber are both engaged in community building at a grassroots level, providing a point of convergence for rising ‘new school’ artists and old-skool stars that welcomes an audience of die-hards and newcomers to the scene. More intimate club nights like these, and more promoters with a creative, holistic approach to hard dance programming, are one way to encourage new female talent and fans.

At an industry level, and for the Dutch hardcore scene in particular, a more proactive approach from label owners, artist agencies and promoters to scout for and nurture women is sorely needed. Accepting that there simply are fewer women artists than men isn’t good enough. Demo drops, open calls and mix competitions, talent stages at events, mentorship programs, workshops, and technical training for women are proactive ways the industry can level the playing field for women who are curious about pursuing careers in the hard dance industry, and could also inspire them with more visible women on festival stages and behind the scenes in management positions.

Read this next: The Producergirls crew share 10 production tips

Most crucially, we need to be open to discussing the issues at hand, and encouraging women to participate in the debate. If more people start to become conscious and vocal about sexism, misogyny, sexual objectification, mental health and the darker, uglier side of the industry, then can we start to find solutions. And we have to do this together.

There are thousands of women in hardcore and we’re all just as diehard as the men – maybe more. We love it for the same reasons: it’s intense, it’s cathartic, it’s heightened drama, it’s fun. It’s political and apolitical and politically incorrect. It’s community, it’s family, it’s home. Most of us don’t want to be known because we are women, but because we are hardcore. We don’t push ourselves forward, so let’s push each other. Girls to the front.

Holly Dicker is a freelance journalist