Features

Features

From Record Player to Turntable: Charting the Evolution 1877 - 2017

The humble record player. Dance music wouldn't exist without it. Here's its potted history.

We take our record players for granted. But how did they get here? Following ground-breaking experiments in France, it was the great American inventor Thomas Edison who first showed off the Phonograph, the turntable’s earliest precursor, to Scientific American magazine 140 years ago. At his laboratory in Menlo Park, California, Edison had assigned one of his trusted creatives, John Kruesi, to the project (making him the device’s true creator).

A stylus recorded sounds onto thick tinfoil wrapped around a cylinder and the first tune a needle ever dropped onto was Kreusi shouting, “Mary had a little lamb.” Within five years, Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, had come up with the Graphophone, which replaced the foil with wax and resulted in higher quality sound reproduction. The record player was taking its first baby steps.

Another inventor, the German-American Emile Berliner patented the Gramophone, which used zinc discs to capture recordings. Proto-records, in other words. Zinc was soon replaced by a rubber-based compound called vulcanite, which in turn was replaced at the dawn of the 20th century with shellac, derived from the secreted resin of an Asian beetle. Where Edison’s phonograph was regarded as a novelty ‘talking machine’ the National Gramophone Company saw the potential in their clockwork-mechanical device for music and entertainment. Shellac discs remained the primary format for music until the 1940s.

By this time, a global market for 10” double-sided 78 RPM (Revolutions Per Minute) records was starting to develop. The early stars of recorded music were opera singers such as Nellie Melba and Enrico Caruso, whose voices echoed beyond the confines of the opera house thanks to the early record player.

Discs and cylinders were in competition as music formats, but demand for the latter now died off. Records were easier to produce, handle and store.

Wind-up record-players were slowly being replaced by their electricity-powered equivalents. Instead of spring-wound mechanics, these used fly-wheel friction discs, as in car clutch systems, to keep record speeds even. At this point, it’s important to point out that record-players and turntables are two different beasts. The radio boom of the 1920s hits the record market hard. Combination home systems started to become more popular, including inbuilt amplification, speaker units and, of course, radio. These were record-players. It’s not until the 1960s that the turntable as we now know it, became an individual entity.

The record industry and, consequently the record-player were in dire straits. The Great Depression all but wiped out sales of both. It was the direst crisis ever to hit recorded music, bigger even than the impact of digitized, non-physical music at the start of the 21st century. In 1934 RCA Victor started selling the Duo Jr, the first component turntable, which was plugged into a radio speaker, however, it was jukeboxes that kept the industry alive during these fallow years. Meanwhile, DJs playing records on the radio were known as ‘pancake turners’.

Technological innovations during World War II led to a leap forward. The Royal Navy had invented wider frequency recording to track submarines, and 16” 33 RPM ‘V-Discs’ were a step closer to records. Peter Goldmark, head of research at CBS-Columbia in the US, worked on 33.3 RPM 12” records with microgrooves that offered much better sound quality. Alongside this he introduced the lightweight tone arm and sapphire needle to turntables. The result of his labours, the 33.3 RPM 12” album on a plastic compound called vinylite (or ‘vinyl’) rather than shellac, debuted in 1948, while rival company RCA Victor jumped in with the alternative 45 RPM 7” disc the following year.

Both became standard speeds and sizes, for albums and singles, respectively, but three speed record-players (including the 78 RPM option) remained popular for a couple more decades, as did mechanized systems that changed records automatically on long central stacking spindles. In the north of England mobile “disc jockeys” such as Bertrand Thorpe, Ron Diggins and Jimmy Savile (yes, that one, unfortunately) premiered the idea of public dances with no band but music instead provided by cutting between two turntables on an amplified sound system. The idea would catch on…

The popular domestic choice was an all-in-one system in a wooden cabinet, but hobbyists – ‘audiophiles’ - developed component systems with separate turntables, leading to a subculture of kit building, utilizing the likes of Garrard or Thorens turntables and Grado Labs phono cartridges. Stereo sounds systems started to appear via Pye in the UK, wherein the stylus moved not just horizontally across the record but vertically, to add another sonic dimension, feeding alternate signals to the left and right channels. At this time the idler-drive, a motor-driven rubber wheel system, was the most popular in-built method for propelling turntables, but this was soon replaced by the more popular belt-drive. The term ‘high fidelity’, ‘hi-fi’ for short, was introduced to describe equipment that offered the best quality sound reproduction.

Alongside the boom in long-playing records for the pop market following The Beatles’ ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ album came a widespread desire for turntables that could do such music justice. The Dual 1009, with record-changer, was a popular choice, but audiophiles increasingly disdained record stacking, as vinyl could easily be damaged.

Massachusetts company Acoustic Research provided a cheap solution with their ‘single play’ turntable but from 1965 the Panasonic division of the Matsushita Corporation launched Technics, a brand designed for the burgeoning hi-fi market which, in 1969, produced the SP-10, the first turntable to utilise a direct drive motor rather than a belt. However, as the’60s closed, Francis Grasso at New York’s Sanctuary club, the granddaddy of modern DJing, was still using belt-driven Thorens turntables with no speed control.

Technics SL-1100 and SL-1200 turntables, from 1971 and 1972, respectively, were designed for home use but the latter gained purchase in the blossoming US disco scene, and later in the hip hop community (alongside the 12” single). Technics decks were tough, powerfully-motored and had accurate timing gauges. DJs from Paradise Garage proto-house original Larry Levan to hip hop’s Bronx inventor, Kool Herc, initially stuck with expensive, high-end Thorens equipment but in 1979 Technics 1200MK2s arrived, advertised as “tough enough to take the disco beat - and accurate enough to keep it,” and specifically geared towards clubland. They were an improvement on the original 1200s, built to absorb more bounce, with a faster start-up speed and a pitch control fader.

They could also handle a new concept that had entered turntable culture – scratching - creatively utilizing the noise made when a record was swiftly moved back and forth at speed. For the next quarter century, despite the appearance of many turntables that boasted advances in one area or another, Technics were the industry standard. At the same time, art-based avant-garde-ists such as Japan’s Otomo Yoshihide and Swiss-American Christian Marclay were abusing turntables in their performances, playing them upside down, adapting them, forcing new noises from them. Their influence would cast a long shadow 20 years later with the rise of turntablism and artists such as Mix Master Mike and DJ Spooky, while DJ Marky’s famous upside-down mixing routine surely owes them a debt.

In terms of home use, the turntable now faded as CDs rose to become the dominant music medium. However, in clubland vinyl was alive and well. Following 1988’s acid house explosion, there was a voracious market for vinyl and decks. The Technics was the staple but a new wave of clubs and DJs, learning from hip hop’s pioneers, were fixated on choosing the best cartridge/needle combo, one that was tough-wearing and supremely accurate. Brands such as Stanton, Gemini, Numark and Ortofon, some of whom had been around for a lifetime, suddenly found their wares in great demand. The mid-‘80s also saw the formation of the Disco Mix Club, a British organization catering for DJs with limited remix editions of songs, megamixes and a new magazine, Mixmag. Their annual DMC Mixing Championships, two years old in 1987, became the benchmark for what DJs playing turntables are capable of.

After a couple of decades of experimental prototypes, The ELP LT-1XA Laser Turntable appeared. Two lasers read the grooves and replicated the music without any wear and tear occurring to the vinyl but, despite impressive audio fidelity, this development didn’t catch on. Pioneer, on the other hand, were experimenting with CD turntables that aimed to replicate the experience of hands-on vinyl manipulation. They went through various iterations throughout the 1990s, notably 1994’s CDJ-500, but only really achieved their goal with the CDJ-1000 in 2001.

The big DJs of the era, however, from Sasha to Jeremy Healy, were still using vinyl. Companies such as Numark, Vestax and Gemini put out competitive turntables but Technics still dominated the market. Some DJs, notably techno heavyweights Carl Cox and Jeff Mills, found the usual two turntable set-up restrictive and expanded it to three.

The early years of the 21st century saw interest in turntables drastically slump. With the rise of digital music files, the vinyl market rapidly died off. Even the mighty Technics 1200s and 1210s went under the axe, their production ceasing in 2010. CD decks were in a better position to adapt. From 2007’s CDJ-400 onwards, for instance, USB ports were included on all Pioneer CD turntables. For a while, though, it seemed as if the future of turntables might be altogether virtual, with laptop, mouse and MIDI (Music Instrument Digital Interface) controlling MP3s and WAVs. Software such as Ableton Live and Native Instruments’ Traktor gave DJs the facility to loop, automatically beat-synch and add effects at a level DJs of previous eras would never have dreamed of. Alongside these developments a new type of turntable started to appear, one whose sole purpose was to process vinyl to digital formats, turning music into data.

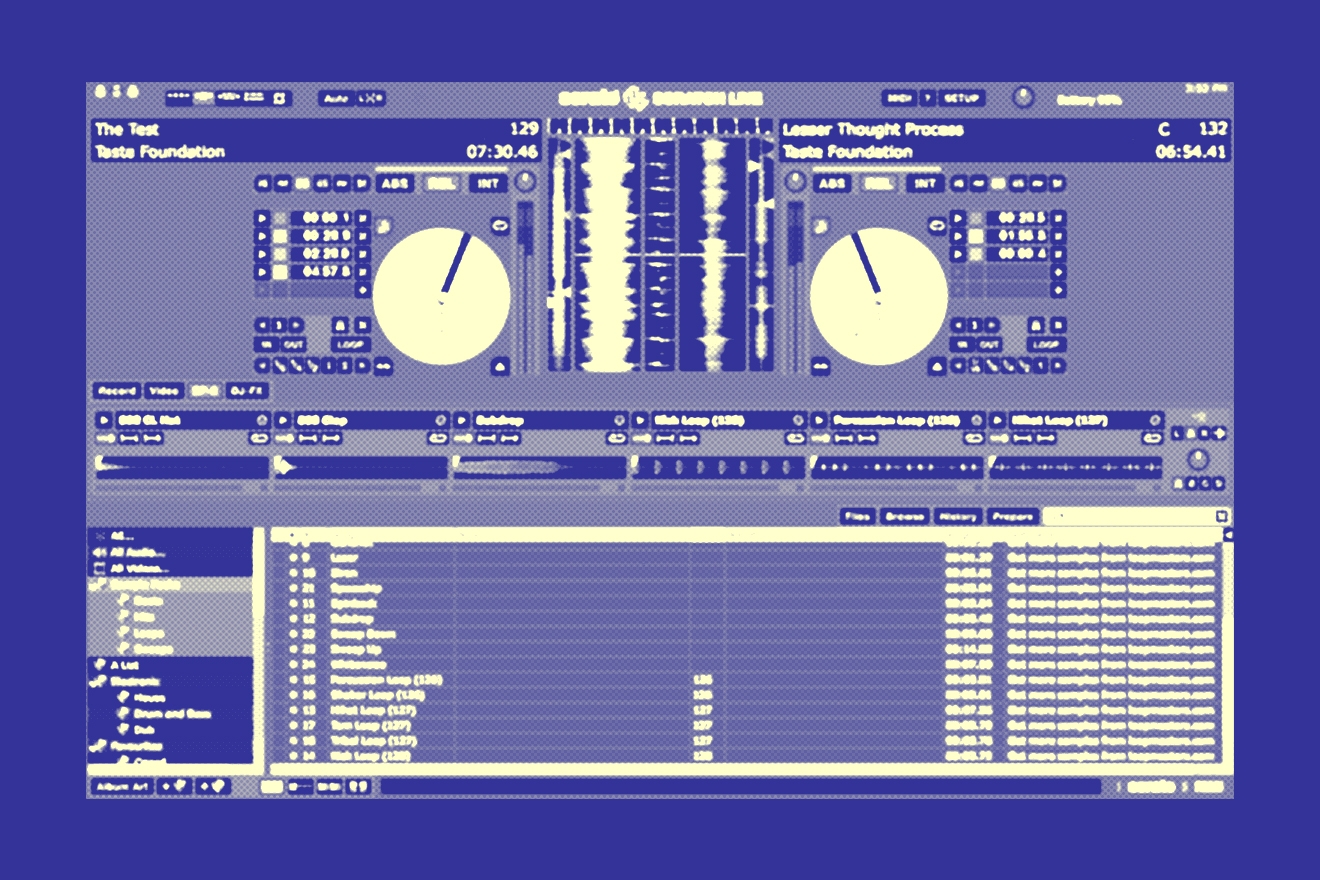

The honeymoon with virtual formats proved temporary. DJs missed the physicality of decks and clubbers didn’t want to watch them fiddling about with laptops, as if they were inputting XL Spreadsheets. Post-Millennium, Stanton’s Final Scratch interface was an early front-runner in allowing digital audio to be manipulated like vinyl via a traditional turntable set-up but it was surpassed by Serato Scratch Live, wherein time-coded control records could be used to manipulate digital formats. This, in turn led to the current Serato DJ package which can be used with decks of not. Meanwhile a plethora of cutting edge turntable technology now caters to both DJs and home-listeners.

Record shoppers using portable turntables test vinyl in-shop on kit such as the suitcase-style, battery-powered GPO Retro Attaché with in-built speakers, then last year Numark adapted this idea with their PT01 Scratch, which added an adjustable scratch switch and non-slip cartridge system for DJing on the go. A multitude of ‘controllers’ now combine CDJ turntable appearance with the possibility of endless studio-style effects and other treatments, meanwhile the vinyl renaissance has been greeted by cutting edge turntables such as the Reloop RP-8000, the Numark TTXUSB, and the Stanton STR8.150, which, between them, incorporate a wild variety of tech, ranging from key correction to programmable MIDI buttons and more.

Technics 1210s have become a collectors’ item so within the last year, back came the all new, almost-the-same-as-it-ever was Technics 1200G and Technics 1210GR, rebooted classics. It’s all a long way from Thomas Edison’s foil cylinder ‘turntables’ of 1877, yet not so very different from the kit used by the first modern club DJs in the 1970s. What goes around comes around. And goes around and around and around at 33.3 and 45 RPM.

Thomas H Green is a freelance writer and regular contributor to Mixmag