Features

Features

Totems of rave: How Vinca Petersen documented the European free party movement

Legendary rave photographer Vinca Petersen tells Seb Wheeler what it was like to document the heyday of the free party movement

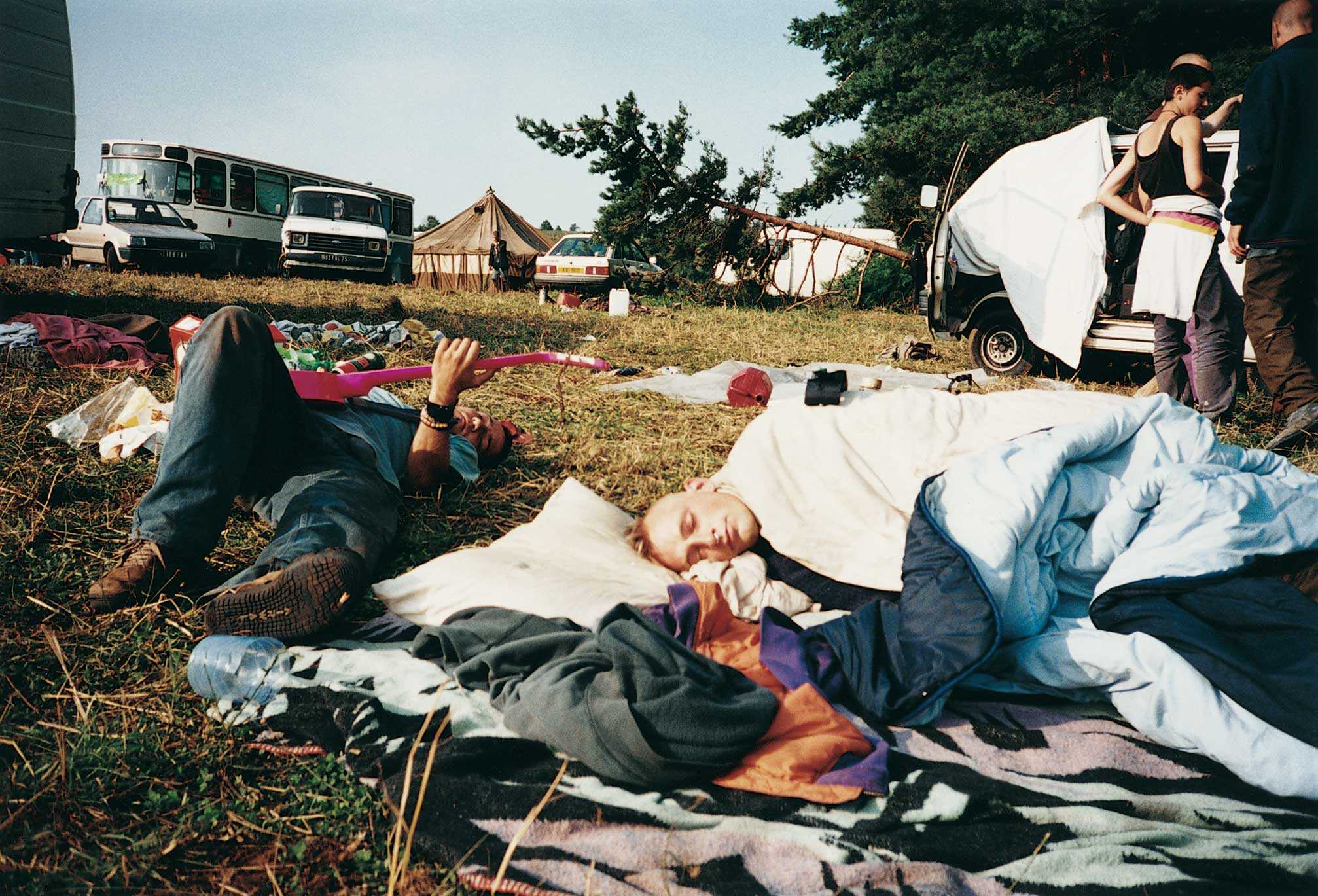

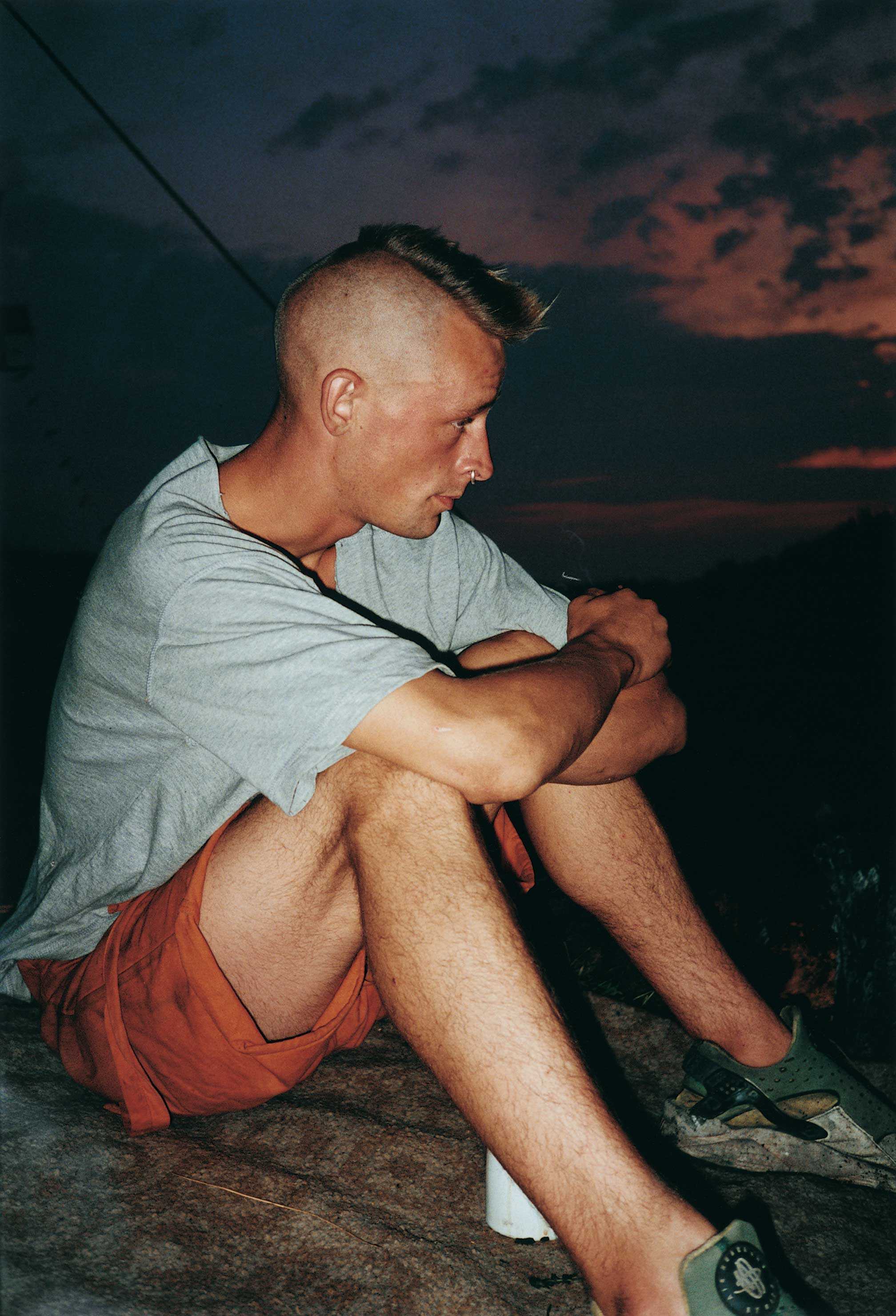

In the 90s, Vinca Petersen was a disciple of rave who travelled across Europe in the wake of the Criminal Justice Bill to throw parties, dance to her favourite soundsystems and live life outside of the rigid boundaries of the 9 to 5.

She documented her time on the road by photographing her friends and the parties they'd organise, collect flyers and newspaper cuttings and diarise her memories as scrawls on rave ephemera or in notebooks.

In the time since she's become a fully-fledged artist and photographer and her documentation of the free party movement has been immortalised in cult tome No System, which has just been republished and gives students of rave a fresh opportunity to check out this long out of print photobook.

The reprint comes off the back of Petersen's inclusion in Sweet Harmony, the first exhibition dedicated to rave that was held at the Saatchi in London in the summer of 2019. Her vast collection of photos, clippings, flyers, notes and other related artefacts was one of the highlights of the show, providing parallel timelines of her personal life in rave and the progression of the free party movement itself.

To celebrate the rerelease of No System, Vinca Petersen shares her memories of life on the road, the process of documenting a culture and why you should always hold on to your memories in the Q+A below.

What was the impact of the Criminal Justice Bill on the parties you were going to and the community you were involved in?

Basically as the parties got bigger and bigger the government got more and more fearful of people gathering in non-commercial autonomous spaces in such large numbers and dancing all night with no care for the police telling them not to. The CJB was an incredibly heavy handed way of stopping that and taking away a huge chunk of our freedom as citizens of the UK at the same time. Not only were spontaneous gatherings of people listening to 'repetitive beats' now illegal, driving towards them was also illegal. It got to the point where friends of mine that were rave organisers were getting arrested on charges of treason. There was only one way to save the soundsystems and save the party: leave the country.

Read this next: Illegal rave crews are using custom apps to evade the police

Was touring Europe with your crew a scary prospect or were you left with no other option to pursue the free party lifestyle?

It was a huge adventure. I have always been strong willed and independent so perhaps it was an easier move for me than for some. But even for less confident people the power of a group of people 'on a mission' and having lots of fun just sweeps you along.

The main ways in which we came up against police were either getting moved along for parking somewhere we weren't wanted or for putting on big free parties. Neither of which seemed to me like something that should be illegal, so I had no fear in breaking those particular laws. I felt I had a right to a certain level of freedom to live and party in the way in which I chose.

You immersed yourself in rave culture. Why is it so special to you?

Unity. Family. Equality. Fun. JOY. Adventure. What is not to like?

What were some of your favourite places to visit and throw parties?

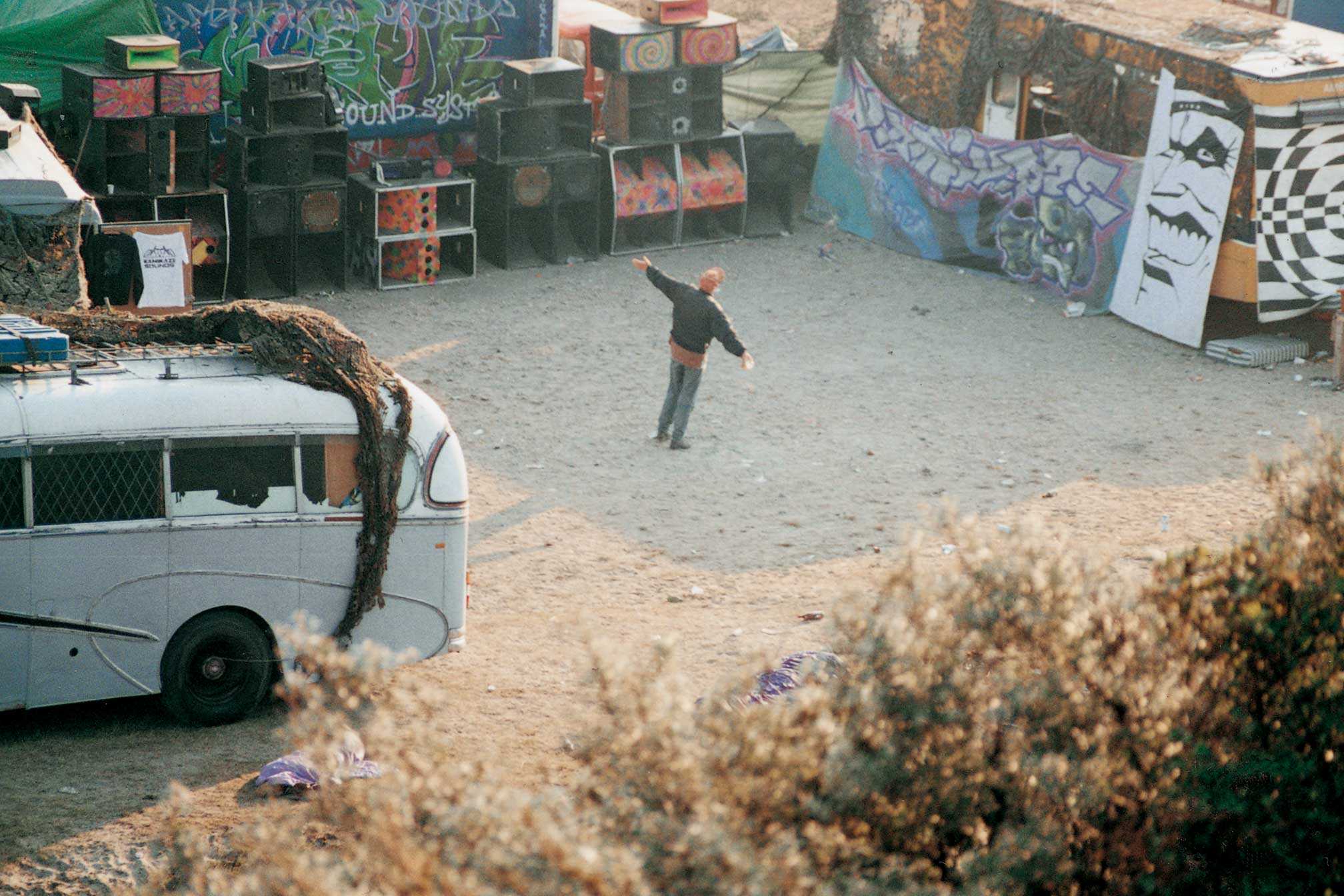

There were so many, and still are so many brilliant places to occupy and party in. In the summer all the soundsystems converged in remote fields to join together to put on Teknivals. The best Teknival sites were ones near a river or lake and with some shadey trees and a view. But often we made do with a boiling hot, dry, shadeless field. Some of my favourite venues were the abandoned ex-Russian Army bases in Germany and Czech. In those forgotten spaces, not only did we not bother anyone but there were lots of things to explore; bunkers, aircraft hangars, hospital buildings and of course runways to drive up and down!

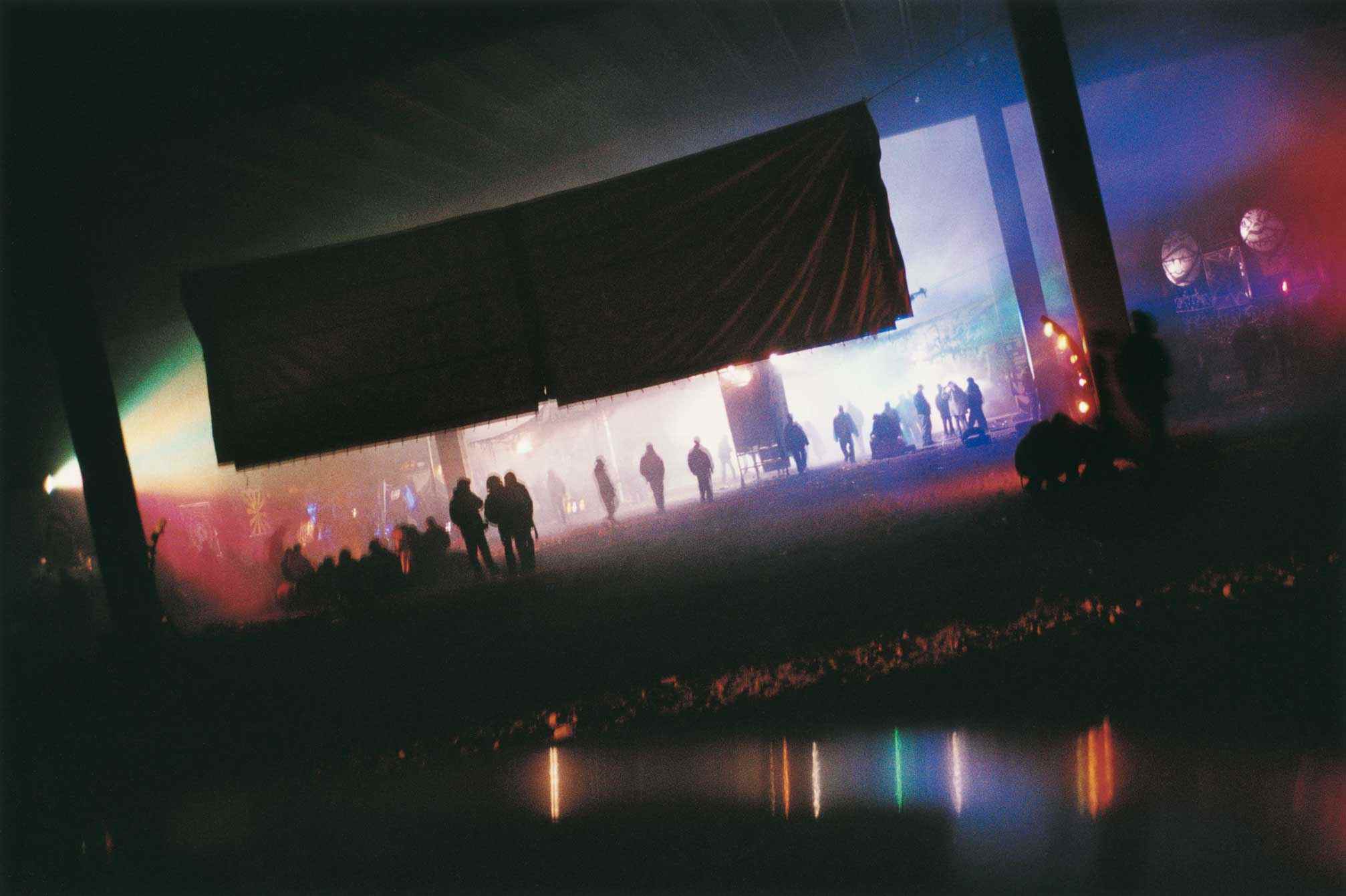

In the winter we took shelter in huge warehouses or established squatted venues. The warehouses were beautiful spaces to occupy. Like cathedrals of rave. We would spend days trying to make them as safe as possible for the ravers, decorating them with backdrops, paintings, sculptures...

Read this next: People are breaking lockdown to attend raves

At what point did you start documenting rave culture?

I never set out to document rave culture, but I have always photographed and written about my life. I also collected ephemera naturally. In the end they came together in my first book No System, but the intention was never there, just an urge to collect memories and totems.

As a photographer, was it easy to shoot so candidly?

I was not seen as 'a photographer' but just as a member of the group. I was photographing my friends for myself and them. I shared my work. I would print everything on small 6x4 prints and show everyone. I lost quite a lot of the negatives, they did not seem important once I had the print in my hand. The print was big enough for a 'family photo album' and that was all I thought I would need them for.

You exhibited photographs alongside diary entries, newspaper articles and other ephemera. Did you keep hold off all of the stuff knowing it would come in handy one day?

Previous to deciding to publish No System in 1999, I had no intention to use any of that stuff, and I have no actual recollection of a conscious decision to keep things. I just did. After 1999 I was more aware of their cultural value.

Read this next: The police are losing the war against the London rave scene

What's your advice for people wanting to document the music cultures they're involved with now?

Turn your images into objects, ie prints. And keep everything. Nothing seems of value in the moment, but in a few years it gathers a personal and perhaps cultural value. After 10 years it's gold.

Forget buying 'stuff' just gather the elements and ephemera of your own personal story.

What is the importance of documenting music culture?

We all know the answer to that! It's everything!

No System has long been sold out – what made you bring it back?

I never wanted it to be exclusive or rare. I wanted anyone that was interested to be able to have one, so when it sold-out and the emails kept coming asking for it and the people kept asking for it, I felt I had to make it available again. During the Sweet Harmony rave exhibition at Saatchi gallery I noticed that my work was as valuable to the younger generations as to any other generation. I actually think the book is beyond me, it has a mission of its own, and it has to fulfil that. It is a brochure for an alternative way of thinking, being and living and should always be available.

Rave culture is at a point where it's being memorialised in museums and books – is that healthy for it? Should we be looking forward too?

Everyone will have a different opinion on that but for me rave culture will never die and the fact that the story of its roots is being celebrated in museums and galleries only makes it stronger. If we think of raves as places where people come together, share an experience of unity, equality, joy and love then we don't want raves to exist only on the fringes, we want raves to be an essential part of life. As a raver in the 1990s I used to feel we were part of a new future and that future is still unfolding – as it says on the back of No System "we exist now and in the future". This summer is going to be a wild one!

What projects are you working on right now?

I am working towards three exhibitions in 2021 at the V&A Dundee, Martin Parr Foundation and the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art. All the exhibitions contain my installations and photos and a good dose of Subversive Joy, the essential ingredient of all my work.

Visit Vinca Petersen's website here and buy a copy of No System here